From the moment your existence begins as an immature egg growing in your grandmother’s womb, everything related to your fertility is finite. But in the bright, open labs of the University of Cambridge, scientists may only be a few years from changing this.

Dr Staša Stanković is just one of them. The computer she works from in Cambridge’s Addenbrooke’s Hospital has seen some of the discipline’s most important data. Now, Stanković turns eagerly from her screen to explain the mysteries her team hopes to understand.

The biggest of which is a woman’s ovaries – and the limited supply of eggs they contain. She describes to me this concept as an hourglass: sand (or, rather, eggs) can only leak in one direction. When it’s almost run out, menopause hits.

“What we are trying to do with our science is control that middle bit of the hourglass,” she says. “We want to narrow it down so that less and less sand falls through during your lifespan. That way, we can preserve the upper part for as long as possible – with the mission to also maintain the quality of those remaining eggs.”

For five years, Stanković has been part of a team working to develop a method that could predict your natural fertility window – and therefore your menopausal age. Already, the test achieves around 65 per cent accuracy, but needs 80 per cent to be considered for clinical practice.

But the team’s focus is also on a solution that comes after the test: a drug that could tackle infertility and, potentially, delay menopause.

Your age at menopause depends on how big your ovarian reserve is at birth, and then how quickly those eggs die during your life. Menopause usually hits when you are around 50 years old and have fewer than 1000 eggs left.

For the 10 per cent of women with early menopause (under 45 years old), and the rare 1 per cent of women who have menopause before 40, this drug could be life-changing.

Your menopausal age

Rather than using physical checks of your ovaries or egg counts, the researchers need just a drop of blood. With this, they can learn about you, your genes, and all the genetic factors that could impact fertility and menopause.

The team has pored over the data of over 200,000 women stored in the UK Biobank. This ‘big data’ includes not only information about these individuals’ menopause and fertility, but pretty much anything else related to their health.

“We have data on how many times you watch television per day, your hormones, diseases you suffer from, MRI scans and more. With those data, we are now starting to build networks between not only reproductive health but also other health outcomes – like dementia or diabetes, for example.”

Thanks to that drop of blood from each of the 200,000 women, the researchers also pieced together the first-ever map of the 300 genetic variants hidden deep in your DNA that are involved in deciding your menopause age.

With this knowledge, Stanković thinks they could finally find the root causes of ovarian conditions like early menopause and polycystic ovary syndrome. After that, a drug battling both could just be around the corner.

“We cannot put all our eggs into one basket,” Stanković warns – referring to IVF and egg freezing. “I feel like a lot of women treat those as magic solutions, not knowing that success rates are incredibly low."

What could the impacts of a menopause-delaying drug be?

The most exciting part of all this, according to Stanković? A next-generation fertility drug that doesn’t just treat symptoms of ovarian diseases but controls ovarian function itself. She thinks this drug could be available within a decade – but she stops short of excitement about the details: there’s still so far to go.

Put simply, the team needs to identify the most important genes, test them on models that mimic the ovarian system, and then develop a drug that maintains the quality and quantity of your egg count as you age. Easy, right?

But at every stage, important decisions need to be made and rigorous testing executed. Already, researchers in the field have used human cellular and animal models on which to test these genes. These include organoids (mini organs grown in a lab – in this case, ones that mimic ovaries) and mice, with experimental gene editing techniques including CRISPR.

Mice do not naturally have menopause. In fact, only humans and some species of chimps and whales do. So the researchers instead recreate the hormonal conditions of a woman’s reproductive system in the mice and organoids to test for fertility and reproductive health.

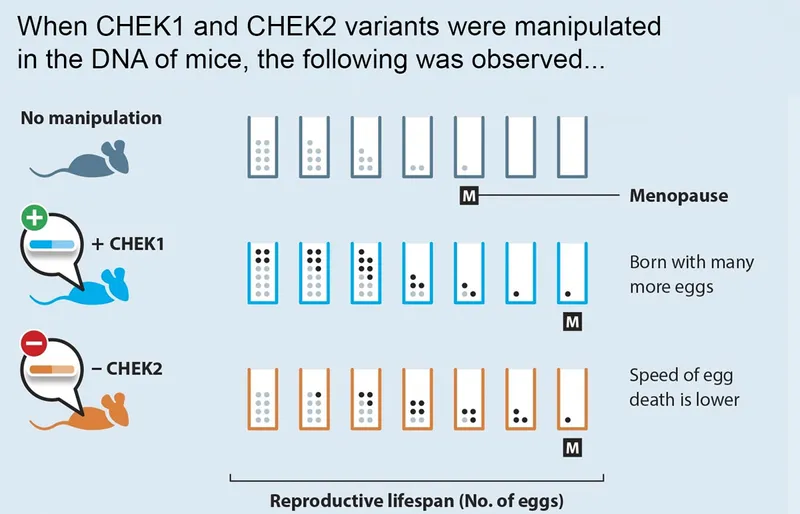

So far, Stanković's team has seen exciting success. In 2021, they took two of the 300 variants associated with menopause, known as CHEK1 and CHEK2. They manipulated them in the mice’s DNA, adding an extra copy of CHEK1 and removing CHEK2.

Both mice exhibited signs of a later ‘menopause’ – and saw an amazing 25 per cent increase in their reproductive lifespan and improved fertility success. “That’s your very first evidence of delaying menopause,” Stanković says. “It was absolutely incredible.”

But, she adds hastily, “There are, of course, a number of scientific questions and safety concerns that have to be addressed before this is attempted in humans."

Besides, while early menopause is linked to diseases like diabetes and osteoporosis, late menopause is linked to reproductive cancers.

For Stanković, this research, crucially, is not just about women being able to have babies for longer, but is also about improving women’s health – given that menopause is linked to several diseases.

Her excitement is evident when she says: “I think one of the biggest impacts we are currently making in women’s health is that, for the first time, we’re actually starting to understand the biological mechanisms behind all these conditions.

“Menopause is an alarm for overall women’s health; it’s intertwined with everything else. We don’t want women to suffer for 30-40 years after menopause hits.”

About our expert

Dr Staša Stanković is an ovarian genomicist with a PhD in Reproductive Genomics from the University of Cambridge. Her 2021 research into the biological mechanisms that govern ovarian ageing was published on the front page of Nature, and her more recent work has also appeared in journals Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey, Cell Genomics, and Nature Medicine.

Read more: