What causes hurricanes?

Hurricanes are some of the most powerful storms on Earth, drawing their energy from warm tropical waters in the Atlantic or north-eastern Pacific. In other parts of the world, these swirling storms are known as typhoons (in the north-western Pacific) or cyclones (South Pacific and Indian Ocean).

All of these storms form above ocean waters when warm, moist air rises. This draws in more humid air from surrounding areas, and as the air rushes in, the Coriolis effect, created by the Earth’s spin, causes it to follow a curved path, leading the developing storm to spin anticlockwise in the northern hemisphere. Meanwhile, as the rising air cools, the moisture condenses out and forms rain clouds.

As long as there’s sufficient heat from the oceans, the storm continues to grow, and it may eventually be intense enough to produce the 119km/h winds that officially define a hurricane.

As the hurricane rotates faster, a calm ‘eye’ of exceptionally low air pressure forms at its centre, surrounded by the strongest winds. The Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale classifies hurricanes from 1 to 5 based on wind speed, with category 5 hurricanes fostering winds of 250km/h and above.

Most hurricanes in the North Atlantic form off the western coast of Africa, and are carried to North America, the Caribbean, and the Gulf of Mexico by the prevailing easterly winds. Once they make landfall, they weaken and dissipate, but not before unleashing devastatingly strong winds and heavy rains on anything in their path, as well as causing storm surges (an abnormal rise in sea level).

An average of six hurricanes are produced in the Atlantic every year, but the 2020 season has been exceptionally active, with eight recorded as of late September.

What conditions do hurricanes need to form?

In the North Atlantic, hurricane season runs from early June to late November. Since hurricanes are fuelled by heat, they only form when upper ocean waters hit 26ºC and above, so they always originate in tropical and sub-tropical regions. The ocean gradually warms over the summer months, reaching the optimal temperatures for hurricane formation in August or September.

Over the summer, the vertical wind shear (abrupt changes in wind speed and direction with altitude) also weakens over the Atlantic. This increases the likelihood of tropical storms ramping up into hurricanes, because wind shear can disrupt the vertical flow of warm humid air and cause storms to break down.

From October onwards, air and ocean temperatures cool and wind shear picks up again, meaning that hurricanes are less likely to form.

Why doesn’t the UK experience hurricanes?

Although hurricanes can travel vast distances, they rely on warm ocean water to sustain them – a large mass of cold water can stop them in their tracks. Located far from the tropics, and with no hurricane-friendly warmwaters, the UK doesn’t experience true hurricanes, but it does occasionally receive the remnants of them.

These ‘ex-hurricanes’ morph as they travel from the tropical Atlantic to mid-latitudes, deriving their energy from the converging of warm tropical air with cold polar air, and often causing high winds and heavy rainfall not dissimilar to hurricanes. A recent ex-hurricane was Ophelia in October 2017, which battered Ireland with record-breaking gusts of up to 190km/h.

Read more about natural disasters:

- How to stop a hurricane

- Can animals sense an impending earthquake?

- What would happen if you dropped a bomb into a volcano?

Is climate change affecting the hurricane season?

Hurricanes are closely linked to warm oceans, so it seems likely that rising temperatures caused by climate change will affect hurricane formation. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that, whilst a warming climate may not affect the number of hurricanes we experience in each season, it is likely to increase their intensity. By 2100, we can expect around 30 per cent more hurricanes and other tropical cyclones to reach category 4 or 5.

Increased moisture in the atmosphere linked to climate change is also expected to generate hurricanes with 10 per cent more rainfall. Rising sea levels could also worsen the damage that hurricanes inflict by making coastal areas more vulnerable to flooding.

The interactions between climate change and the many factors that affect hurricane formation are complex, so it’s difficult to attribute any one hurricane directly to climate change.

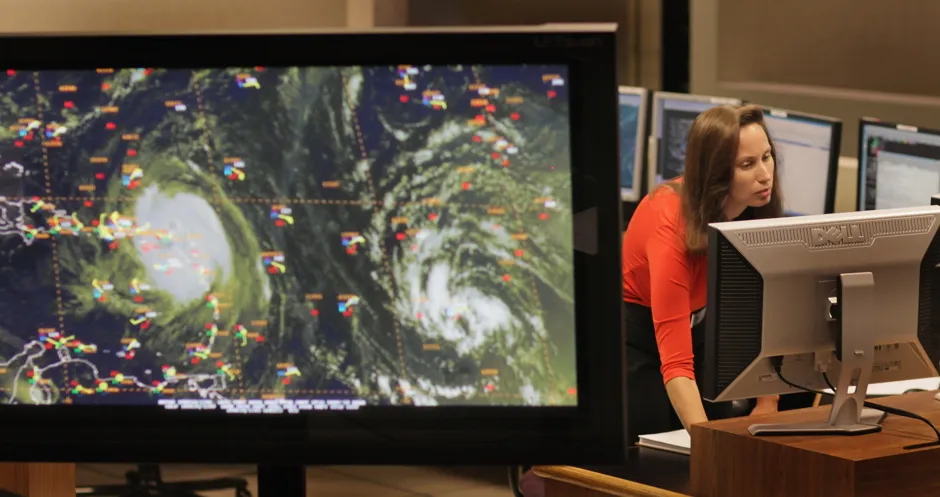

How are hurricanes predicted?

Hurricane prediction has two components: predicting the intensity of hurricanes, and forecasting where they’re likely to make landfall. Both are complex tasks, since a multitude of interacting factors, from humidity to thunderstorm formation, come into play, but intensity forecasting is the most challenging, as it requires an understanding of relatively small-scale phenomena, such as the atmospheric circulation within a hurricane’s eye.

Recent decades have seen huge improvements in our ability to predict where a hurricane will hit, thanks to improved satellite observations and ever more powerful supercomputers. Meteorologists build computer models that use data on previous hurricanes and current weather conditions, along with equations describing how the ocean and atmosphere behave, to calculate a hurricane’s most likely track. In the 1980s, track forecasts were off by an average of 650km – nowadays this has dropped to 185km.