You would be forgiven for assuming that finding a continent twice the size of Australia would be easy, but that was not the case with Antarctica.

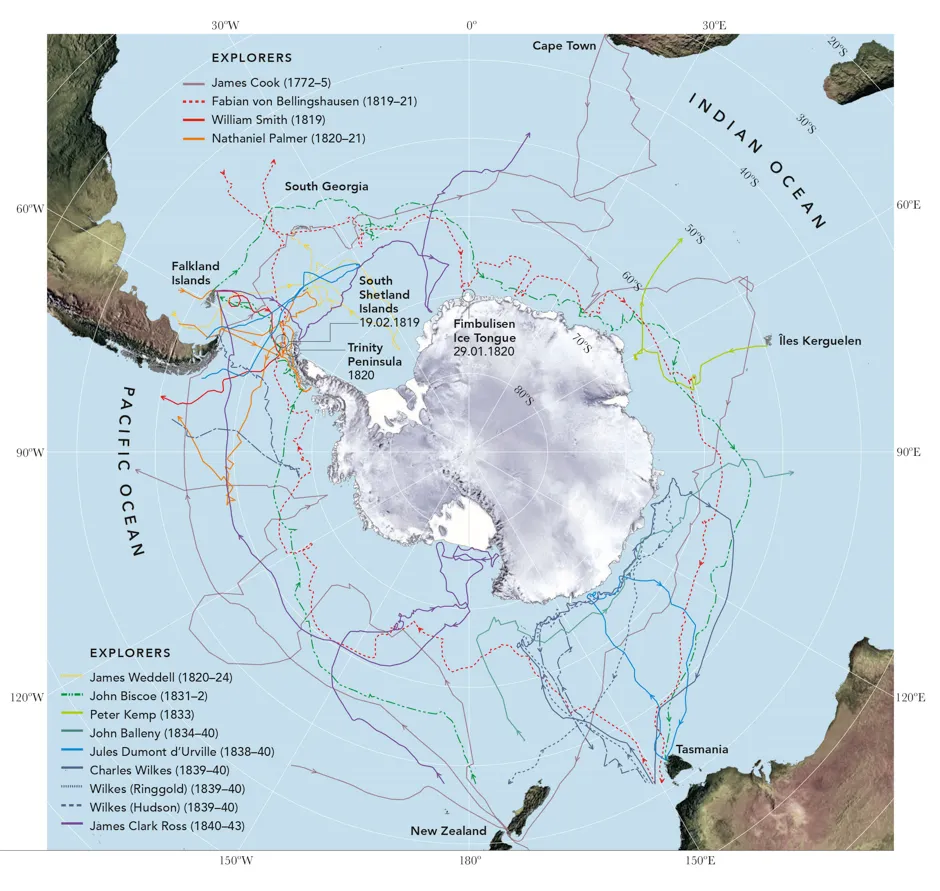

Captain Cook, one of history’s greatest navigators, tried circumnavigating the Southern Ocean twice in the 1770s, but he never set eyes on land, unable to penetrate the dense barrier of pack ice that surrounds the coast. From the mountainous icebergs he sighted he surmised that land must exist further to the south but that it would be so desolate it would not be worth the effort of finding it. He was right that land existed, but he was wrong about its value.

It was another fifty years before Antarctica was eventually sighted, and then, by three explorers almost in the same year. Exactly who ‘discovered’ the continent is a matter of debate among scholars, and that debate revolves around exactly what constitutes Antarctica.

The first claim is by William Smith, the British captain of a freighter who was on his way around Cape Horn to Valparaiso. Smith was running south in Drake Passage to avoid one of the devastating storms that are frequent in that part of the world. As dawn broke on 19 February 1819, he saw the tall, rocky island that now bears his name.

The island is part of the South Shetland Islands, the northernmost archipelago in Antarctica. Closer inspection showed that the coast played host to many fur seals, a potential goldmine for sealers, and Smith knew it. He sailed on to Chile, eager to keep his discovery secret until he could inform the British Admiralty office in Santiago. When he arrived there, the Admiralty commandeered his ship and placed a navy captain, Edward Bransfield, in charge.

As soon as spring arrived, they sailed back to the newly discovered islands. What a shock they must have had! By the time they got there, several other ships were already traversing the island chain. They belonged to sealers. William Smith may not have given the game away, but his sailors had gossiped in port, and the seal hunters, knowing the value of pristine hunting grounds, had sailed as soon as they heard the news.

Read about Antarctic research:

- Penguins help researchers identify the most vulnerable areas of the Antarctic

- How to grow food in space: the Antarctic base preparing for human space colonies

- Antarctica rainforest once basked in 19°C summer temperatures

Captain Bransfield landed and claimed the territory for Britain on 2 February 1820. He pushed further south and discovered Trinity Peninsula, the northern part of the Antarctic mainland, but did not land there.

Nathaniel Palmer, an American sealer, has the honour of being the first to set foot on the mainland, on 17 November 1820.

Another captain could, however, claim to have seen the mainland before him. The Russian Fabian von Bellingshausen was circumnavigating Antarctica around the same time. Like Cook, he had been sent on an official expedition to find southern lands, in his case by the Russian government. Also like Cook, he came close to land on many occasions, only to be beaten by the pack ice. On 27 January 1820, he spotted a high wall of ice on the southern horizon.

Today, we know that the position he recorded is near the terminus of the Fimbulisen Ice Tongue, the large, floating extremity of one of Antarctica’s great ice shelves. He had probably seen that part of Antarctica, but this barren ice was not what he was hoping for, and it lent weight to Cook’s claim that any land would be worthless. Von Bellingshausen had seen an ice shelf – but was it land?

So we have four contenders for discoverer of Antarctica: Smith, who saw the outlying islands; Bellingshausen, who saw the ice shelf; Bransfield, who sighted the mainland and Palmer, who landed on it. I will leave it to you to decide who found the continent of Antarctica.

Extracted from Antarctic Atlas by Peter Fretwell, published 26 November (£35, Particular Books).

- Buy now from Amazon UK, Bookshop or Waterstones