This summer has seen extreme weather right across the Northern Hemisphere, seemingly far beyond what has been seen in previous years. Widespread heatwaves have been observed on every continent, with weather records being broken left, right and centre. On 27 June, Oman reported a night-time temperature that never dropped below 42.6°C, a world record for the highest minimum temperature within a 24-hour period. Across the Red Sea, in the Sahara Desert, a new continental record maximum daytime temperature of 51.3°C was observed. Elsewhere on the planet, local temperature records have been broken in regions as diverse as the Arctic Circle, the US, Japan, Greece and the UK.

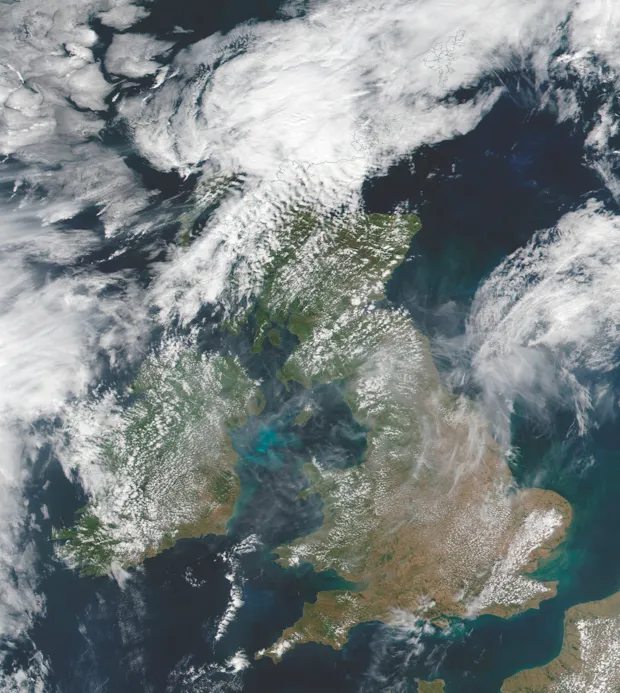

In many places the heat has been made worse by a lack of rain, which, if present, takes some of the energy from the Sun in the form of evaporation, thereby leaving less of the ‘felt heat’ in the surrounding area (a form of heat meteorologists call latent heat.). Satellite images of Great Britain show a clear and striking browning of the entire country for this summer compared with last, and hosepipe bans have been put in place in some counties to conserve water.

Inevitably, hand-in-hand with hot, dry conditions come wildfires, and much of the hemisphere experienced widespread loss of forests, other vegetation, and human lives. Nowhere more so than Greece, where wildfires were visible from space, with strong winds compounding the outbreak, spreading the fires faster and dispersing the ash to the surrounding regions, leading to Hollywood-style apocalyptic scenes of raging fires and ash-covered streets below an ominous red sky.

But in this world tainted by human-induced climate change, are these extraordinary weather events really a surprise? Some caution is required here, because while it’s true that Earth’s land has warmed by 1.6°C since pre-industrial times, climate and weather patterns other than global warming can play critical roles in all types of extreme weather, including those seen this summer.

El Niño, a well-known global climate pattern that’s associated with central Pacific ocean temperatures, causes even warmer heatwaves, and indeed led to 2016 being the warmest year on record. But this summer El Niño has been in a neutral phase, meaning that the widespread extreme heat occurred without the help of this natural mode of variability – making the heat and wildfires even more extraordinary.

Another factor in climate variability is the jet stream, which is responsible for extreme weather in the mid-latitudes. The high-intensity winds of the jet stream circumnavigate the globe at around 10km above sea level and facilitate the movement of atmospheric waves, similar to the waves we observe on the beach but far larger in scale. Much like waves on a beach, these atmospheric waves can break, which is what we saw over northern Europe and Japan, creating weather patterns known as atmospheric blocks – regions of high pressure. But the European blocking this summer was special: relentlessly static, and almost as if it was nailed in place over Scandinavia. The consequences? A complete blocking of any cooler and unstable weather coming from the west, along with the creation of cloud-free regions over northern Europe and the UK, leaving the land at the mercy of direct sunlight.

When it comes to these climate patterns, it’s often about what side of the jet stream you are on, so while the UK has been experiencing months of sought-after beach weather, Iceland for instance has been experiencing a dreary, wet couple of months. Understanding how climate change may alter the exact position of these patterns is therefore of high priority, but also proving to be particularly problematic. The consensus is that summer blocking conditions are unlikely to increase in duration, and indeed may decrease at low northern latitudes, as the blocking systems migrate polewards due to climate change.

The future may have a whole bunch of uncertain circulation patterns in stores for us, but you can be sure that these patterns will be superimposed on a background of much warmer air, making it extremely likely that heat waves and wildfires like this year will become the norm in the decades ahead. Indeed, if we don’t act to stabilise our climate now, a typical weather report in 50 years’ time may read, ‘Conditions this year are relatively cool, with temperatures and wildfires akin to those of 2018’. Let’s not wait to see what an extreme summer looks like in that world.

This is an extract from issue 326 of BBC Focus magazine.

Subscribe and get the full article delivered to your door, or download the BBC Focus app to read it on your smartphone or tablet. Find out more

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard