Look at a packet of Quorn mince and you’ll discover that a 75g serving contains 10.9g of protein, 3.4g of carbohydrates and 0.4g of saturated fat. Later this year, a glance at the packet will tell you something else: that producing the 75g serving released the equivalent of 0.16kg of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Since 2011, Quorn Foods has been working with researchers at Sheffield Hallam University and Innovate UK, a non-departmental public body, to calculate the carbon footprint of its meatless products. Now it has had the information certified by the Carbon Trust, and plans to add it to product packets later this year.

Doing so should, says Quorn Foods, “better [inform] people who want to understand the environmental impact of the foods they buy”. But will the move really help Britons understand and lower their dietary carbon footprint – and how close can we get to a zero-carbon diet?f

Read more about carbon footprints:

- Which vegan milk is best for the environment?

- How to reduce your carbon footprint for next to nothing

Judging by the volume of media coverage on the subject, consumers are increasingly interested in cutting their carbon footprints. Focusing on food is a good place to start.

According to a 2012 study, food-related processes release about one-fifth of the UK’s total annual greenhouse gas emissions, or 167 million tonnes of CO2e.

Greenhouse gas emissions are often measured in CO2e – carbon dioxide equivalent – for simplicity. This is a single measure that includes the warming potential from all greenhouse gases emitted by a given industry, including carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxides and so on.

Carbon footprints are no mean feat

There’s another reason why Brits wanting to lower their carbon footprint should begin with their diet: it’s one aspect of our lives over which we have a relatively high degree of control.

“Many people are in rental accommodation so there’s little they can do to make their home more energy efficient, and they don’t necessarily have much choice about transportation to and from work,” says Prof Peter Scarborough at the University of Oxford, who researches population, nutrition and sustainability. “But diet is absolutely something they can choose to change.”

This doesn’t necessarily mean that footprint labelling on food will help UK consumers lower the carbon cost of their diet. For several years now, nutritional ‘traffic light labels’ have been added to some foods.

Scarborough has conducted research into the way UK consumers respond to such traffic light labelling, but has found that it is difficult for people to use the information to make decisions.

Even when you account for transportation, the Spanish tomato still has a much lower carbon footprint than the British

Prof Adisa Azapagic

If, for instance, one product has two ‘green lights’ and two ‘red lights’, a consumer might legitimately wonder whether it is healthier than a rival product with one ‘green’, one ‘red’ and two ‘ambers’.

Likewise, a consumer standing in the food aisle might find it difficult to quickly work out whether the carbon footprint of a pre-prepared Bolognese sauce is higher or lower than the carbon footprints associated with a tray of minced beef, an onion, some fresh basil and a bag of fresh tomatoes.

Read more about diets:

- Life in the (intermittent) fast lane: the health benefits of time restricted diets

- Ultra-processed food and the risk of death: will fish fingers and fizzy drinks kill you?

Speaking of tomatoes, they highlight another problem with carbon footprint labels: apparently identical food items can differ drastically in their carbon costs. Last year, Prof Adisa Azapagic and her colleagues at the University of Manchester published a study on the environmental impact of vegetable consumption in the UK, including the carbon footprints that different vegetables carry.

Azapagic’s team concluded that putting one kilo of UK-grown fresh tomatoes on the British dining table produces 12.5kg CO2e. Perhaps surprisingly, putting one kilo of foreign-grown tomatoes on the table produces just 1.3kg CO2e.

The explanation for this, says Azapagic, is that the climate in the UK means tomatoes must be grown in greenhouses that are heated mainly with electricity. Spanish tomatoes don’t carry this carbon cost because tomato plants thrive in warm Mediterranean fields.

This neatly punctures another popular misconception: that imported products must have a higher carbon cost than local food because of transportation. A lot of food is transported by boats and lorries rather than planes, and in environmental terms the cost of transportation is usually tiny compared with the cost of actually growing the food.

“Even when you account for transportation, the Spanish tomato still has a much lower carbon footprint than the British,” says Azapagic.

Why should we eat less meat?

So, if eating local won’t make a difference, what will? The answer, says Scarborough, is to eat less meat.

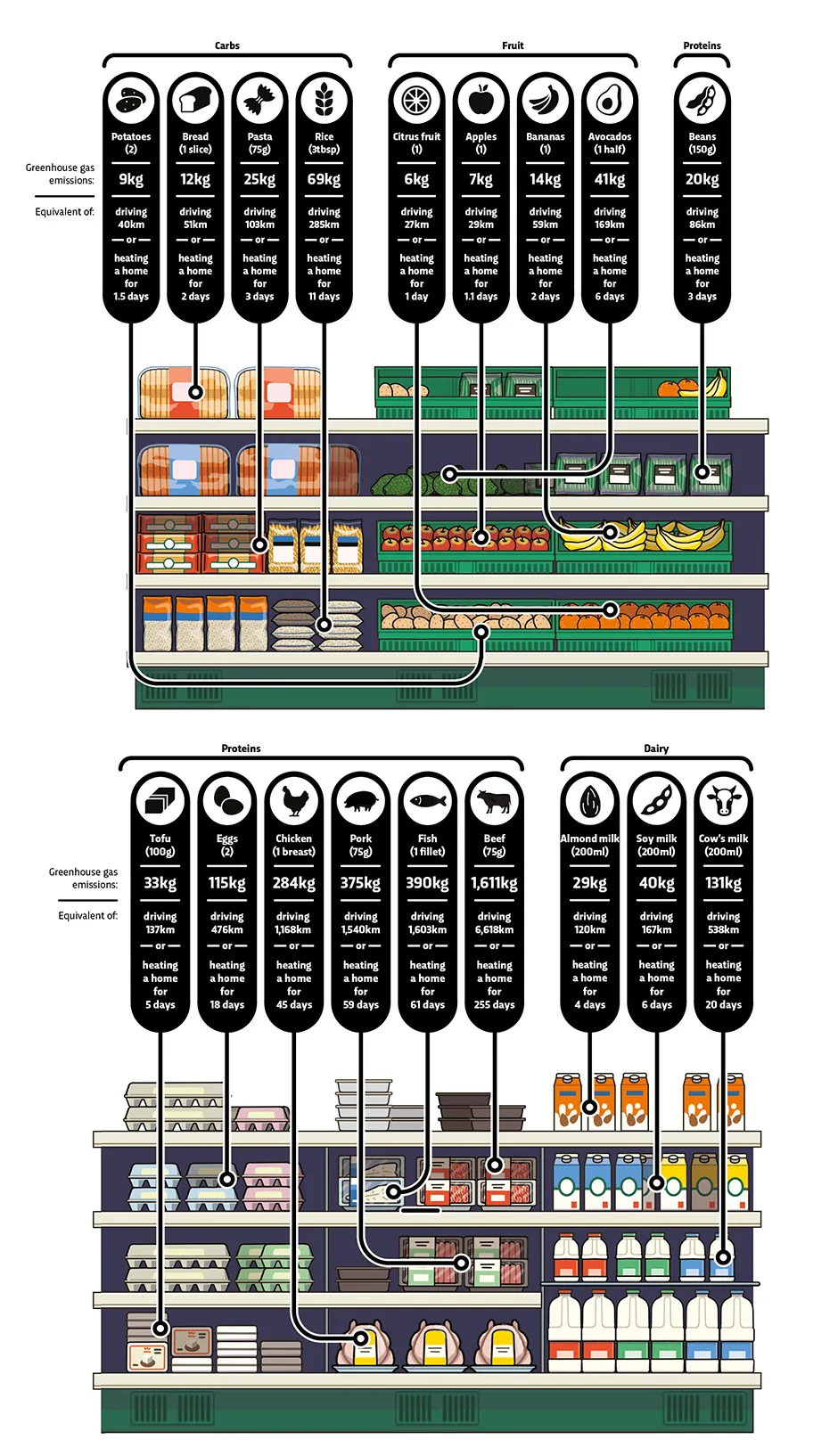

In 2014, he and his colleagues calculated the carbon footprints of various British diets. A meat-eater diet released between 4.7 and 7.2kg CO2e each day depending on how much meat it contained – the vegan diet released just 2.9kg CO2e. Vegetarians and people who eat fish but not meat came out in-between: their daily diets released 3.8kg and 3.9kg CO2e respectively.

One reason meat has such a high carbon footprint is that livestock is typically fed grain that could instead be given directly to humans. Animals then use the energy in that grain for all manner of processes including maintaining body temperature and keeping their internal systems functioning.

A relatively small fraction goes into building the muscle and other tissue we consume as meat, making the process of ‘growing’ meat extremely inefficient – although Scarborough says the problem isn’t as bad for small animals like chickens. “You don’t have to feed a chicken anywhere near as much [as you must feed a cow] to get a kilogram of meat,” he says

Read more about vegan diets:

- Vegans and vegetarians at 'lower risk of heart disease', but have increased chance of stroke

- Can I raise my dog or cat as a vegan?

Even so, all meat carries a relatively high carbon cost. Perhaps in recognition of this fact there has been an upsurge in the number of vegans in the UK.

According to some estimates, there are 600,000 British vegans today – four times as many as in 2014. But vegans in the UK are still outnumbered roughly 100 to 1 by non-vegans.

Even if people are convinced of the environmental benefits of going vegan, they may be reluctant to make that shift. They might even balk at the idea of replacing lamb or beef with low-carbon alternatives: swapping a beef burger for a locust burger, for instance, or trying what might be the next food trend: lab-grown meat.

The problem is that the number of animals in the food system right now is overwhelming it

Prof Peter Scarborough

Prof Ermias Kebreab, a biologist and ecologist at the University of California, Davis, thinks that there might be a way to sidestep this reluctance. If we are unwilling to change our own diets, then perhaps the solution is to change the diets of the animals many of us eat instead.

Last year, he and his team demonstrated that by supplementing animal feed with about 1 per cent by weight of a particular strain of seaweed, they could half the amount of methane that cows belch into the atmosphere – known as ‘enteric methane’.

This is because the seaweed reduces the ability of microbes in the cow’s stomach to generate the methane: the animals burp out larger quantities of hydrogen gas instead, which has an indirect, smaller impact on global warming.

“Most of the emissions [associated with cattle] are from enteric methane,” Kebreab says. “So, if you are able to reduce the emissions by 50 per cent – that’s absolutely huge.”

Encouraging though this is, it doesn’t reduce the carbon footprint of beef and lamb to the level of beans or pulses, says Scarborough. Supplementing livestock diet with seaweed can’t change the fact that most of that animal feed consists of grain we could eat ourselves.

Some consumers might protest that the beef on their plate comes from ‘pasture-raised’ cows that ate grass rather than grain – but Scarborough says many of these animals are actually brought into cow sheds at night and given grain.

Can we still have some meat?

At this point, one might be forgiven for concluding that Scarborough and researchers like him will only be satisfied when all of us have adopted a vegan diet. He stresses that this is far from being true.

In fact, he says, some scientific models suggest it is slightly more efficient to have small numbers of livestock in the agricultural system than none. For instance, in manageable quantities, animal manure is a useful fertiliser. “The problem is that the number of animals in the food system right now is overwhelming it,” he says.

It’s not about giving up meat, says Scarborough, but eating far less of it. Doing so is good for animal welfare too. If we eat less meat, we can ‘afford’ – from an environmental perspective – to allow farm animals to live a free-range life rather than raise them through intensive farming.

In other words, British consumers should be able to adopt a diet with good environmental and ethical credentials – if they are willing to eat no more than about one portion of meat per week.

Read more about food:

Dr Graham Horgan and his colleagues at Biomathematics and Statistics Scotland designed an algorithmthat aims to nudge people towards making those kinds of dietary changes.

It assesses someone’s food shopping list and, using data on the range of carbon footprints associated with each product, suggests relatively small tweaks that should reduce the carbon cost while still meeting nutritional requirements. For instance, the first thing the algorithm does is increase or reduce the quantity of any given item on the list by up to 50 per cent.

Then it considers adding small quantities of foods not on the shopping list – a tin of mackerel, for instance – that can provide key nutritional requirements at a relatively low carbon cost. “Our approach was to try to avoid saying ‘cut out red meat altogether’ and simply say ‘eat less red meat’,” says Horgan. “I feel that might be more acceptable to consumers.”

People assume food habits are stuck for life, that people don’t change – but it’s absolutely not true

Prof Peter Scarborough

Just by making these changes, about 50 per cent of people in a 2016 study published by Horgan and his colleagues could continue to eat meat but also reduce the carbon footprint of their diet to a level where it released only 3.1kg CO2e per day.

This isn’t too much higher than the 2.9kg CO2e per day for a vegan diet that Scarborough calculated. Horgan now wants to test whether the algorithm can have a real-world impact on the dietary choices made by average British consumers.

Beyond cutting down on meat there is at least one more thing consumers can do to lower their dietary carbon footprint: learn to appreciate the value of food. Some estimates suggest that the food we buy but then throw away adds up to 214 calories per person each day.

But an analysis published earlier this year concluded that the problem is worse than that. Dr Monika van den Bos Verma and her colleagues at Wageningen University & Research in the Netherlands found that each of us, on average, actually wastes 527 calories each day.

Alarming as this conclusion is, she points out that it also represents a golden opportunity. “Yes, it’s a bigger problem than we thought,” she says. “But that means if we can solve it, it’s a bigger solution as well. That’s a big ‘if’, but I think we can do it.”

Right now, there isn’t much stigma associated with throwing away bread that has gone stale, or bananas that have overripened. But what we deem socially acceptable can change relatively rapidly, as we’ve seen in recent decades with public perceptions of smoking.

With more awareness about the time and energy that goes into producing food, we might be more willing to turn stale bread into breadcrumbs, or overripe bananas into banana muffins. Or we might simply become better at purchasing just the food we need, rather than bulk-buying products and throwing food away.

Scarborough agrees that attitudinal shifts to food are possible. “People assume food habits are stuck for life, that people don’t change – but it’s absolutely not true,” he explains. “If you look at the food we consume now versus 60 years ago it’s very different.”

Read more about climate change:

- The ocean captures twice as much carbon dioxide as previously thought

- The road to net zero: how we could become carbon neutral

Consumers should be able to adopt lower-meat diets and waste less food, not least because this is what most British people have done for centuries. So if we can make those changes, will it bring the zero-carbon diet into view?

In one sense, the answer is a firm no: we will always need to use energy to produce even the most frugal of diets. But eventually it may be possible to offset most – or even all – of the emissions associated with our food, particularly if more of us reduce our meat consumption.

This is partly because with less demand for pasture it will be possible to ‘rewild’ agricultural land, and an acre of forest can absorb far more carbon than an acre of pasture. No one has run the numbers, but it’s an intriguing idea, says Scarborough.

“The question of whether the food system as a whole can be zero-carbon over the long run? That’s an interesting one.”