Salt has a life far beyond the dinner table. From land speed records to ancient lakes, this mineral is intimately tied toour lives and our land.

Scorching salt

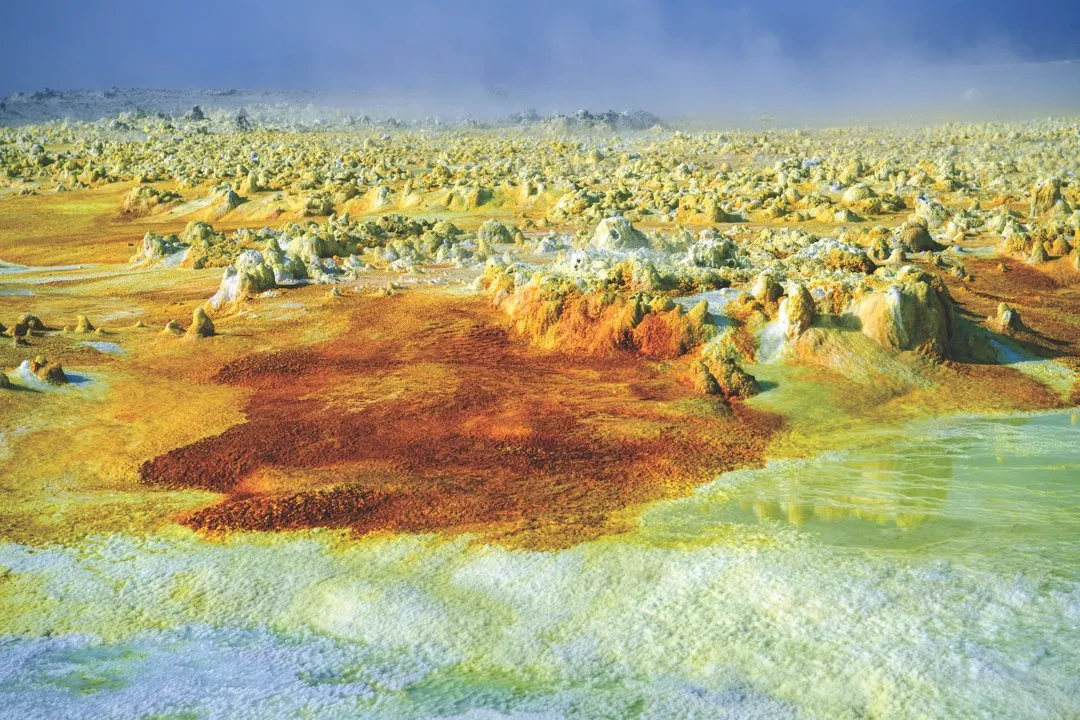

The Danakil Depression near Dallol, Ethiopia, is an alien landscape on Earth. At 100 metres below sea level, the cratered ground barely contains the volcanic activity beneath it, spitting out hot water that dissolves salt and other minerals.

It’s stiflingly hot and dry – approaching 50°C some days – and the ejected water quickly evaporates, leaving behind vibrant-coloured deposits. Sulphurous yellows mingle with iron-rich browns and turquoise tints of copper in boiling pools.

It’s no place for hard physical labour, but that hasn’t deterred the hundreds of workers – Afar people – who come here with axes to cut the salt into slabs, known as ‘tiles’, for $5 a day.

Although trucks are now allowed in to transport the tiles, the Afar people are wary of the encroachment of modern technology, which could devalue the products of their traditional trade.

See more picture features on Science Focus:

- Monster movers: 6 massive machines for shifting rockets, turbines and even ancient buildings

- The masters of natural disasters

Dead loss

The Dead Sea is a health tourism hotspot for those who believe in the medicinal benefits of a natural salt bath. The water here is about 10 times saltier than open seawater, partly because the salt has nowhere else to go – this ‘sea’ is actually a saltwater lake trapped in the Jordan Rift Valley. And with water levels dropping by more than one metre per year, it’s getting even saltier.

Dr Nadav Lensky, who heads up the Dead Sea Observatory in Jerusalem, says it’s likely that human activity rather than natural processes will determine how far levels drop and if the lake will eventually dry up. The potash industry has a big impact on the lake, pumping water from the deeper northern basin to the southern shallows to create evaporation pools for producing potassium salts that are used in fertiliser.

In this image, trees and bushes that once grew on dry land perish in the southern end’s salty pools.

Abstract algae

This striking image may resemble abstract art, but it’s actually a photograph of the salt ponds of southern France. The white shapes around the rock are crusts of dried-out salt, while the water is red because that is the colour of a community of microbes living in the pond.

At lower levels of salinity, blue-green algae dominates, but as evaporation draws the water out, the colours change to those of species that can withstand the saltiest of saltwater. Orange and red pigments called beta-carotenes are the chemicals made by salt-tolerant organisms like the algae Dunaliella salina and halobacteria. Brine shrimp also make versions of the same pigments, adding to the vivid colour palette.

Flat out

As any speed junkie worth their salt will tell you, Bonneville is the place to be if you’re serious about speed. The salt flat pictured here, measuring 10,000 square kilometres, is a remnant of Lake Bonneville, a giant salt lake that dried up 14,500 years ago.

Engineer Eva Håkansson is gearing up her electric motorcycle ‘KillaJoule’ to compete in the 2017 Bonneville Motorcycle Speed Trials. While the salt doesn’t make for a pleasant ride – it’s rougher than regular roads and at high speeds you feel every bump – it does provide a vast, featureless plain to race on. “There’s nothing to hit and no neighbours to disturb,” says Håkansson.

At the 2017 trials, she reached 411km/h (255mph), leaving her petroleum-powered competition for dead. But she says such speeds may become harder to achieve in future, as climate change will interfere with conditions on the salt.

Rose-tinted view

The rose-coloured tinge of these slabs of Himalayan salt gives them the appearance of sugar-dusted Turkish delight.

The salt, which is mined at the Khewra Salt Mine in the westernmost tip of the Himalayas, is one of Pakistan’s most famous exports. Miners work by the light of gas lamps, using gunpowder to blow it from the walls. After being cut into slabs, the salt is transported by truck to Karachi, some 20 hours’ drive away.

In the UK, Himalayan pink salt sells for around twice the price of regular table salt. Claims about its health benefits abound, with articles citing its 84 trace minerals. There are no scientific studies to back up these claims, but the mineral content explains why the salt is the colour of confectionery.

Harvest time

The coastal province of Bac Liêu, Vietnam, is the size of Luxembourg, and roughly one-tenth of its land is devoted to producing salt.

The salt fields are flat and open, allowing seawater to wash across. Hot, dry conditions make the water evaporate quickly, meaning more salt. In the rainy season, salt output declines. This area produces up to 165,000 tonnes of salt a year, enough for over 350 billion packets of ready salted crisps.

The back-breaking work of raking the salt into piles and carrying it away in baskets is done by farmers in the blazing heat; they will often work from sunrise to sunset. Most don’t have space to store what they harvest, so the market value is dictated by dealers who stockpile the salt until they can sell it at a good price.

- This feature was first published in the July issue of BBC Science Focus - subscribe here.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard