Life has had a bumpy ride on planet Earth. On five different occasions over the past 450 million years, at least three-quarters of all species on land and sea have been wiped out. It’s easy to think of these mass extinctions as events in the distant past that bear no relation to what might happen to us in the future – but that couldn’t be further from the truth.

New research into what killed off the dinosaurs in the ‘End-Cretaceous’ extinction – probably the best known of all mass extinctions – is giving us a window into our future by helping us to answer some important questions. As are the other mass extinctions. If life on our planet gets progressively harder, which species alive today will survive and which will perish? Would human intelligence and technology actually improve our chances of survival, or not?

Read more about the extinction of the dinosaurs:

Now is a good time to ask these questions. In May this year, the UN published the most comprehensive report ever written on the fate of all living things on our planet: the Global Biodiversity Assessment. It doesn’t make for happy reading. With input from 450 of the world’s brightest minds, who synthesised 15,000 scientific papers and government reports, it states that no fewer than 1,000,000 animal and plant species are threatened with extinction – many within decades. It led to headlines that we are now in, or on the brink of, planet Earth’s sixth mass extinction.

Google “what killed the dinosaurs?”, or ask most palaeontologists, and you’ll get a fairly clear answer: a 10km-wide asteroid or comet slammed into Earth 66 million years ago, in what is now Mexico. “It hit with the force of over one billion nuclear bombs, releasing a huge amount of energy,” says Dr Steve Brusatte, a palaeontologist at the University of Edinburgh.

As well as creating the 100-mile-wide Chicxulub crater in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, it unleashed wildfires, tsunamis, earthquakes and hurricane-force winds. “A lot of animals would have died in the immediate aftermath, particularly if they were within 1,000 miles or so of the impact,” says Brusatte.

The impact choked the atmosphere with dust that blocked out much of the incoming sunlight for several years. “Plants wouldn’t have been able to photosynthesise, and ecosystems would have collapsed,” says Brusatte. Then came 1,000 years of global warming. “The asteroid hit a big carbonate platform [a large body of carbonate rock such as limestone and dolomite] which caused a lot of carbon dioxide to be released, so there was a pulse of global warming,” says Brusatte.

“So you had immediate, mid-term and long-term killers. These things combined to kill off the non-avian dinosaurs, along with so many other animal species.” The only dinosaurs that survived were those that eventually evolved into today’s birds. In all, three-quarters of the Earth’s species were eradicated.

Not so fast…

But while the Chicxulub impact is often said to be the sole cause of the dinosaur-toppling mass extinction, there’s growing evidence that this was not the case. In the hundreds of thousands of years running up to the asteroid impact, volcanoes in what is now India went into overdrive, and Earth’s temperature was yo-yoing, as were the sea levels. This tangled web of factors has led to disagreements about the chain of events that caused the dinosaur extinction, and what was the main culprit.

Proponents of the ‘impact hypothesis’, as it is known, suggest it was the asteroid impact that supercharged the volcanic eruptions in the Deccan Traps in west-central India. Others are not so sure. In March 2019, research published in Science dated ash from the volcanic activity in India with unprecedented accuracy.

“We showed that the volcanic eruptions went in pulses, with the major pulse lasting about 20,000 years and ending with the mass extinction,” says Prof Gerta Keller, a palaeontologist at Princeton University, who was involved in the research. “But there is no evidence of the asteroid impact causing the volcanic pulse.”

According to this and other research by Keller, the volcanoes set themselves off and played a major role in the death of the dinosaurs. It’s a complex web. Even just unpicking the effects of the volcanoes in India is not straightforward. The CO2 they released would have caused global warming, while conversely the sulphur dioxide involved would have had a cooling effect. To make matters worse, the dinosaur fossil record is patchy, making pinning cause to effect tricky.

Read more about extinction:

- Pride before a fall: why human narcissism will be our undoing

- When the planet breaks, maybe this is how we'll fix it

But what the last 20 years of research into the End-Cretaceous extinction does show is that several environmental factors conspired to wipe out the non-avian dinosaurs. Not only that, but they died out rapidly. It’s now thought that, after being successful for 160 million years (diversifying into over 1,000 species around the world), most of them became fossil fodder in little more than 10,000 years.

The situation the dinosaurs were confronted with has obvious parallels with today. “We have biodiversity loss, habitat loss, climate change and resource extraction,” says Dr Lauren Holt, a researcher at the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (CSER) at the University of Cambridge. “And we also have pollutants – chemicals in the wrong place that are causing further fragility to the system.”

Water wipeout

Another mass extinction – the ‘End-Permian’ extinction, 252 million years ago – provides further evidence for how rapidly things can go awry. In this catastrophic event, the seas were almost sterilised – 96 per cent of marine species were wiped out. Seventy per cent of land species were annihilated, too. By picking through fossils preserved in rocks in southern China, a team of geologists and palaeontologists from the US and China announced in 2018 that all this death and destruction took place in just 60,000 years, possibly even less – the blink of an eye in geological terms.

“It shows us that any future mass extinction is going to happen really fast,” says Dr Jahandar Ramezani, an MIT geologist who was involved in the study. “It’s like there’s a tipping point, and once you reach that, everything is going to hell.” It’s thought that, just like the End-Cretaceous extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs, volcanic activity on a monumental scale – this time in Serbia – was partly responsible for the End-Permian event.

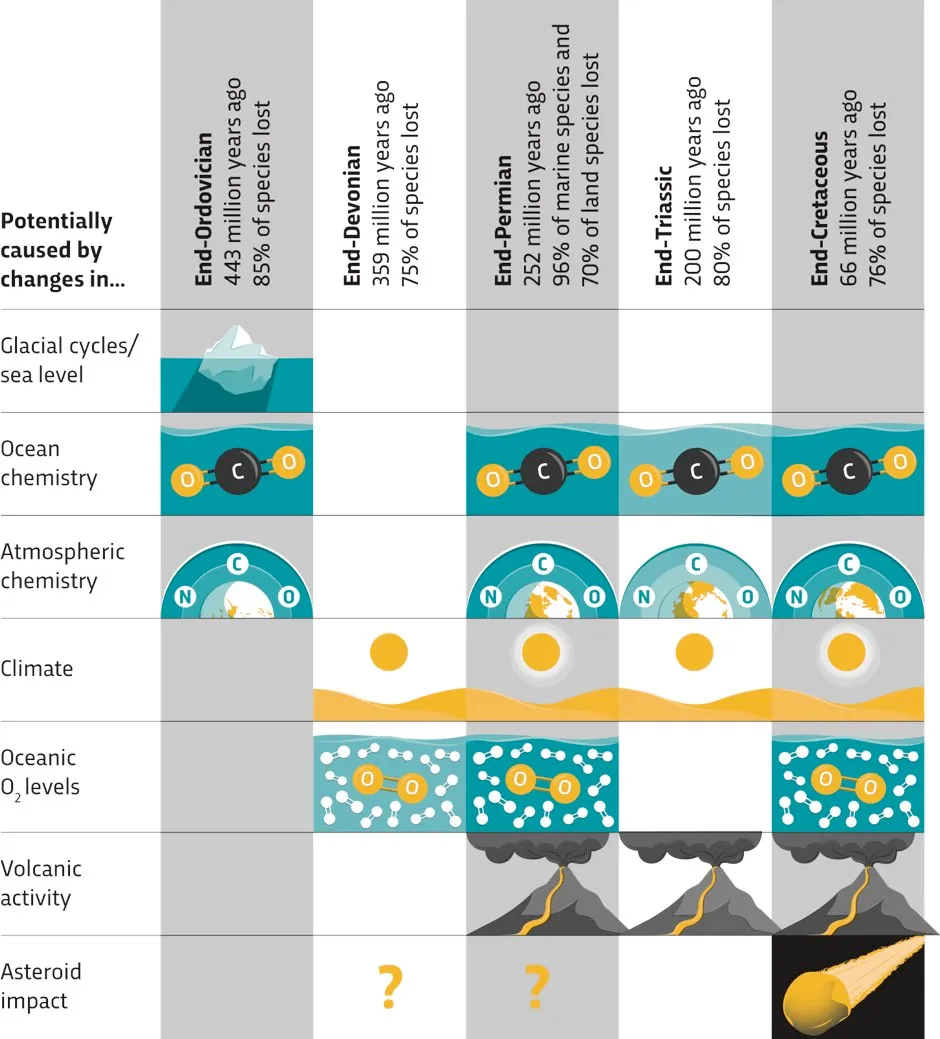

But other factors had a hand, too, including a reduction in oxygen levels in the deep oceans and changes in atmospheric chemistry. In fact, a cocktail of environmental problems is thought to have been behind all previous mass extinctions.

The five mass extinctions

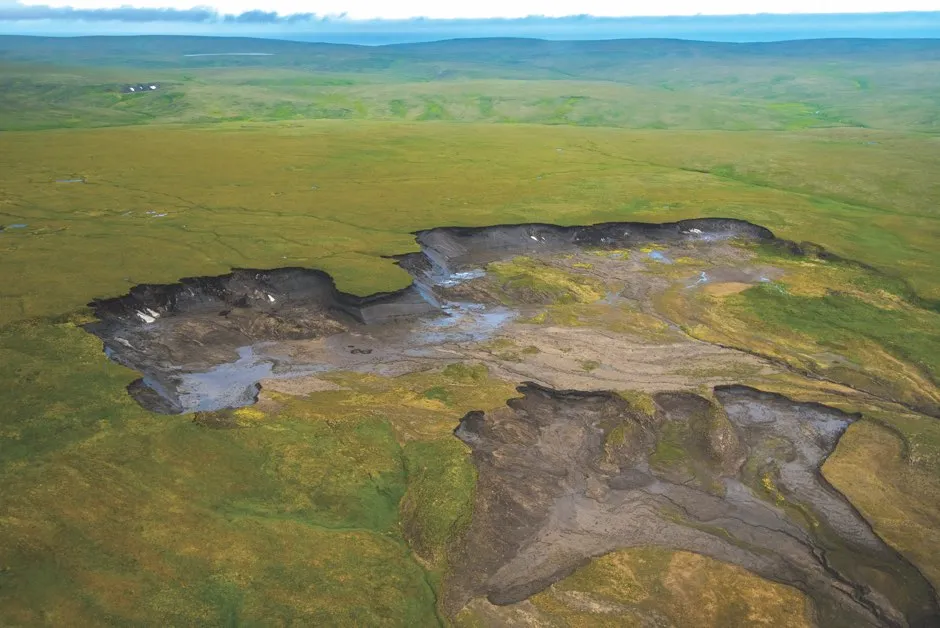

Today, potential tipping points in the Earth’s climate are the subject of intense research by scientists trying to figure out just how warm things will need to get before a sudden, irreversible change to the climate takes place. The Arctic is an area of particular concern. If the permafrost melts here, it will release huge volumes of carbon dioxide and methane (both greenhouse gases) into the atmosphere.

Meanwhile, if the snow and ice melts, Earth’s surface will be less reflective, so less sunlight will be bounced back into space. If these things happened, climate change would be supercharged. Understanding when these tipping points might occur will go a long way to predicting when the next mass extinction might be.

Adapt to survive

But let’s not forget that, as destructive as the previous mass extinctions were, some life did survive. In fact, the extinction of the dinosaurs was good news for the mammals, whose numbers exploded. So what would our chances be in a future mass extinction?

The signs aren’t good. “I think the biggest thing the previous mass extinctions show us is that even the most dominant, successful, widespread and diverse groups can die out,” says Brusatte. “The dinosaurs were on top, and then very quickly they were gone. Now we are in the position that the dinosaurs once were.”

Learn more about dinosaurs in our podcast with Steve Brusatte:

The dinosaurs were specialists, highly adapted to the ecological niches they inhabited, which allowed them to dominate. In mass extinctions, however, it’s the generalists who tend to win out, as they can better adapt to the changing environmental conditions. “It probably means that the subway rats and pigeons would have a better chance of surviving than the elephants or polar bears,” says Brusatte.

There’s another pattern in what happens to life during mass extinctions: animals tend to get smaller. In what is known as species dwarfing, or the ‘Lilliput effect’, fossil records show that the average size of everything from molluscs to microbes and mammals tends to shrink. Exactly why this happens is unclear, though one possibility is that smaller individuals grow and reproduce faster, and the shorter times between each new generation means they can adapt more quickly to the harsher surroundings.

So in a future mass extinction, it’s probably the smaller generalists that will come out on top. But there’s a good chance that we humans will also have a say in what lives and dies, by pooling more effort and resources into saving certain species. “One of the things that will play a huge role in species’ survival chances is the extent to whichthey’re seen as important to human wellbeing,” says Dr Simon Beard, who is also a researcher at Cambridge’s CSER. “So we’re quite likely to see animals and plants such as sugarcane, cows and bananas continuing to dominate the global biosphere.”

The human factor

While there are parallels between previous mass extinctions and what is currently happening, there’s no escaping one key difference – these environmental changes have been brought about by human activity. That does mean, however, that there’s something we can do about it. For all its bad news, the UN’s Global Biodiversity Assessment says that it’s not too late to make a difference.

One thing previous mass extinctions tell us is that we should avoid just focusing on the atmospheric aspect of climate change, says Beard. “Mass extinctions have always been largely marine phenomena, since the majority of Earth’s biodiversity exists in the oceans. The most destructive changes we currently face may thus be the phenomena of declining levels of oxygen and increasing acidification of the Earth’s oceans. These are being driven by increases both in global temperature and atmospheric CO2.”

Then comes the awkward question of whether Homo sapiens would ultimately survive. Previous mass extinctions suggest that our survival depends on the answer to a key question – are we specialists or generalists? That’s not a straightforward question to answer.

We have become a successful species through immense individual specialisation – by becoming skilled at doing specific things, such as developing technology that allows us to fix the human body, or to grow food in hostile environments. “If we evaluate each individual’s chances of survival, we really look like toast,” says Beard. Collectively, however, we are generalists. “We can survive in space, in Antarctica, in deserts and underwater,” says Beard. “All we need is technology.” So that’s the paradox we will face if environmental conditions really turn nasty.

“Humanity is amazingly adaptable and creative,” says Beard. “It’s about having the curiosity to solve these problems. If we can do that, there’s a good chance of us making it through. But if we can’t, then there is a real chance of a total systems collapse. In that case, each of us is on our own. We can’t survive that way – it’s simply impossible.”

Our creativity needs to be applied carefully, though, says Lauren Holt. Take genetic engineering – techniques such as CRISPR gene editing have been suggested as a way to do everything from making coral more resistant to rising sea temperatures, to creating plants that suck more CO2 out of the atmosphere.

“I don’t think people fully understand the long-term implications of things like CRISPR technology on the stability of genomes,” says Holt. When an organism’s genome is unstable, it’s more likely to mutate, causing disease. “If we send organisms out into the world that have augmented ecology, we don’t know if that’s stable.”

As well as the safety of technological fixes for extinction, there are some wider questions to address, too. “Being an adaptable generalist rather than a vulnerable specialist is often referred to as ‘resilience’. but it’s important to accept that resilience is costly,” says Beard. “To be adaptable and resilient, we need to develop traits such as redundancy, so we have a backup system in place; preparedness, allocating resources to deal with the most unlikely of potential threats; and flexibility, not being too attached to how things currently are.”

The trouble is that businesses and governments are striving for efficiency rather than these other traits, says Beard.

So if we can take anything from previous mass extinctions, it’s that unity, cooperation and developing a little resilience will make us less like the dinosaurs and give us the best chance of fighting off mass extinction number six.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard