Ecologist Emma Olliff doesn’t want her own children. Not biological ones at least. She made the decision quite young, she says, but she only fully consolidated the reasons why in her early 20s.

“I did a marine biology degree, and then a biological diversity masters,” she says. “And so was made very aware of human impacts on the environment, and how more of us is only going to make it worse.”

She isn’t alone. The idea of reducing the number of children you choose to have – or even going child-free – for environmental reasons has had a surge of interest in the past few years, with a particular focus on the climate impact of adding another person into the world. For example, notably Prince Harry recently stated that he and Meghan, Duchess of Sussex will have a maximum of two children. Others also say they are concerned about bringing children into a world with such an uncertain ecological future.

But not everyone is convinced about the merits of focusing on population as a solution to the world’s environmental woes. Some people point to the dark history of enforced population control by political leaders or movements.

All this feeds into a debate on how much emphasis should be put on reducing the number of people on the planet to tackle climate change.

What is the definition of overpopulation?

Olliff is a board member for Population Matters, a UK charity that campaigns for people to have smaller families as a way to increase sustainability. And there are some influential environmentalists among the charity’s patrons, including Sir David Attenborough, Jane Goodall and Chris Packham, which gives weight to the argument.

Indeed, few people would dispute that there is some physical limit to how many people can live on Earth sustainably in the long time. There are currently 7.7 billion people on Earth, and this could rise to 9.7 billion by 2050 and 10.8 billion by 2100, according to UN projections. But the actual increase will depend hugely on what happens with policies, healthcare and culture over the next decades.

The picture is much more complicated than ‘fewer people means lower emissions’

So how many people is too many? Trying to answer that is tricky. Even defining the term ‘overpopulation’ is hard. “Ask eight different people [and] you get eight different answers about what overpopulation means,” says Raywat Deonandan, associate professor in global health at the University of Ottawa, and an expert in epidemiology.

Deonandan himself retreats to the standard demographer definition of overpopulation: the point at which a population exceeds the land and ability to sustain it. But this opens up the question of what ‘sustain’ actually means. “Traditionally ‘sustain’ just meant ‘keep you alive’,” says Deonandan. “It’s not really what we mean any more.”

In climate terms, sustainability translates into the need to maintain a relatively stable climate, which a report from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) last year showed means lowering emissions enough to keep global temperature rise to no more than 1.5°C.

Most of the carbon budget for this has already been used up, explains Kimberly Nicholas, associate professor in sustainability science from Lund University in Sweden. “So if we’re going to avoid dangerous climate change, which I really hope that we do, we have to radically and rapidly reduce emissions that we have today. That’s flying and driving and burning fossil fuels and raising livestock.”

Overpopulation or inequality?

The IPCC recognises population as one factor in greenhouse gas emissions. Its projections show that, if all else is equal, lower populations in the future will support lower emissions, and the most sustainable future scenario has a population lower than today’s.

But the picture is much more complicated than ‘fewer people means lower emissions’ for one very clear reason: inequality.

The average greenhouse gas emissions emitted per person vary hugely from country to country. They sit at around 20 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per year for each person living in the US, for example, but around two tonnes per year for Indian citizens. In the UK, they average seven tonnes per year. And this isn’t even accounting for the many products made in Indian factories that are consumed in the UK and the US.

Read more about the world's population:

- Anthropocene: the mark of mankind

- Chris Packham: “ Our greatest worry of all is human population growth, in my opinion”

This means that where babies are born tends to influence their total climate impact significantly, with people born in high-consumption, rich countries far more likely to lead high-emitting lifestyles.

Another way of looking at emissions inequality comes down to wealth. An Indian businessman flying often by private jet will have far higher greenhouse gas emissions than other Indians on average, while a British person living in food poverty is likely to have low emissions compared to their compatriots.

The poorest half of the global population is responsible for only around a one-tenth of global emissions attributed to individual consumption, according to a 2015 report from charity Oxfam. The richest 10 per cent globally, meanwhile, are responsible for around 50 per cent of the emissions, and have carbon footprints 60 times as high as the poorest 10 per cent.

Would you give up having children to save the planet?

These stark figures show why the climate impact of population size simply cannot be thought about in a silo, according to Dr Katharine Wilkinson, co-author of Drawdown, a book which highlights the most effective solutions to tackle climate change.

“If we had just a billion people on Earth but people were wildly consuming fossil fuels and industrial agriculture was growing and people were eating beef five meals a day, you can imagine a scenario where the population’s very small and actually the impact is still really significant,” she says. “Similarly, if we have a large population but consumption comes way down then that’s also a different scenario.”

Those in the rich world who have decided to have fewer or no children for climate reasons often make this argument. “The impact of our children is considerably more than the impact of children in areas where the birth rate is so much higher,” says Olliff.

This argument is supported by an oft-cited scientific study published in the journal Environmental Research Letters in 2017. The study reviewed the available research on the actions that people in rich countries could take to reduce their climate impact.

“Basically we wanted to know, as an individual in an industrialised country, what can I do that really makes a difference for climate change, that would most reduce my carbon footprint,” says Nicholas, who co-authored the study.

There are many horrible human rights violations that have happened in the name of ‘solving’ overpopulation

The study found that four choices were consistently high impact in cutting emissions: eating a plant-based diet, living car-free, avoiding flying and having one fewer child. The biggest impact choice of these? Having one fewer child, which would save 58.6 tonnes of carbon per year. The next most effective was living car-free for a year, which would save 2.4 tonnes. “That was basically showing every child that we would choose to create in a high-emitting country has a huge carbon legacy,” says Nicholas.

Assigning responsibility to a parent for a child’s emissions in this way is contentious. Some say a child’s emissions aren’t part of their parents’ ‘carbon footprint’, while others note the risk of framing things in terms of ‘too many people’. “There are certainly many deeply problematic and racist and xenophobic and horrible human rights violations that have happened, or been proposed, in the name of ‘solving’ overpopulation,” says Nicholas.

It also puts an emphasis on personal lifestyle choice, which some say comes at the expense of a focus on more systemic changes to tackle climate change. Effort should go instead to tackling the underlying issues of reliance on fossil fuels and overuse of resources, according to this perspective.

Listen to episodes of the Science Focus Podcast about population:

- What does a world with an ageing population look like? – Sarah Harper

- How can we save our planet? – Sir David Attenborough

- The future of humanity – Michio Kaku

- Are Generation Z our only hope for the future? – John Higgs

“I’m not a fan of burdening global care to the choices of individuals, who must often make personal choices against their personal self-interest,” says Deonandan. “To me it makes more sense to create economic incentives and disincentives to guide populations into making more sustainable choices.”

But others argue individual action can scale up to bigger changes. “I think you need individuals to feel engaged and empowered in their sphere of influence that what they can do actually makes a meaningful difference, to get enough people activated to actually solve the problem,” argues Nicholas.

Still, as Wilkinson adds, the climate crisis will absolutely not be solved by individual behaviour change alone. “To the degree that people are thinking about individual behaviour change, I think it’s really good to have a rigorous grounding for that,” she says.

The average emissions per person remain highest in rich, industrialised countries like the US. But population growth has also tended to level off in these countries.

In poorer countries earlier along the ‘demographic transition’, such as India and much of Nigeria, rising populations and a growing middle class increasingly need – and, many argue, deserve – increasing resources. But if these economies develop in a high carbon way, this could lead to rising emissions.

This is why many see supporting people in poorer countries who want to have fewer children as key to reducing emissions globally. Educating girls and family planning are two of the most effective measures for tackling climate change, according to Project Drawdown.

Research also shows that women and girls are particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change because their roles as caregivers, and providers of food, fuel and water puts them particularly at risk if drought or flooding occurs. This increases the stakes for ensuring they are protected yet further.

“If you actually look at their impact together, educating girls and family planning, or as I prefer to talk about, closing the gaps on access to reproductive healthcare, then it actually turns out … to be the number one solution,” says Wilkinson.

Your human population questions:

- How small can a population be and still survive?

- What is the current death/birth rate ratio in the world per year?

- What is the ratio of males to females on the planet?

- What is the ratio of people being born to people dying on any given day?

Access to good quality family planning is recognised by the UN as a human right and is known to benefit the health and welfare of women and their children. It also brings down fertility rates. Similarly, women with a higher education level tend to have fewer, healthier children and manage their own reproductive health more actively.

Education and reproductive healthcare are things that women and girls should have, says Wilkinson, noting that around the world there are still 132 million school-age girls not in school, and 214 million women who say they have unmet needs for contraception.

“They [education and reproductive healthcare] happen to have these positive ripple effects when we start to add up the individual decisions that a woman or a family makes across the world, and over time start to have real impacts at scale,” she says.

At the same time, it is crucial to avoid the dangerous and problematic territory where the reproductive choices of women are controlled or determined for them one way or the other, she adds.

Similarly, for those in richer countries who may be considering having fewer children due to climate change, the most important thing is that it is a personal decision. “It’s got to be something you choose and you’re happy to choose,” says Olliff. “I’m just trying to raise awareness to make more people feel happy about choosing that decision.”

- This article was first published in issue 340 of BBC Science Focus - subscribe here

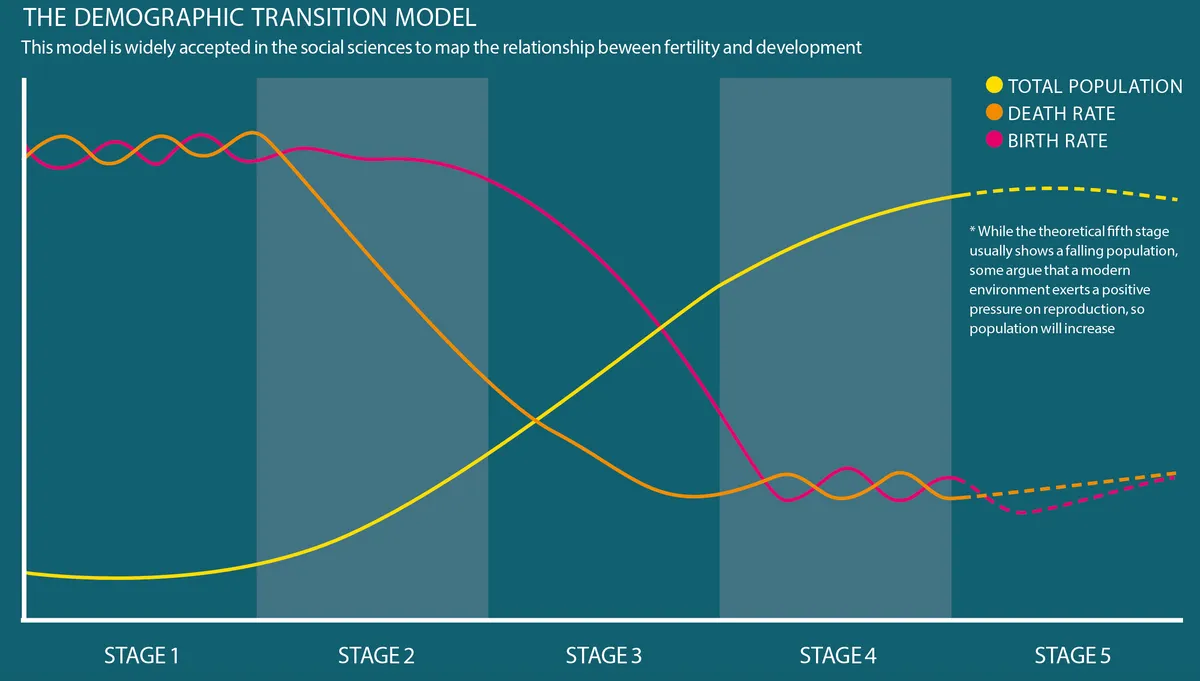

The demographic transition model

This model is widely accepted in the social sciences to map the relationship between fertility and development

In the first stage, there is a low population but a high birth rate, which is balanced by a high death rate. People are dying of famine, and there is a high child mortality rate. Life is short and harsh and there is a high incentive for having lots of children, because most are going to die.

In the second stage, the death rate starts to decline due to improved health measures, such as better food, clean water and vaccination. Birth rates remain high and the population starts to rise.

The third stage sees the birth rate start to drop due to social innovations such as educating girls, family planning and moving to cities.

By the fourth stage, as seen in most of the Western world, there is a large population that is still growing slowly, with a low birth rate and a low death rate. The fifth stage is still theoretical, but shows a high population that starts to slowly fall, due to low birth rates and ageing.

Some countries, such as the UK, moved through the stages slowly. Others, like China, passed through the demographic transition model extremely quickly. However, the demographic transition is not inevitable, and requires investments, policies, education and support.

In the (more theoretical) fifth stage, the population is still high but starts to fall slowly as the birth rate drops below the death rate. This stage is now beginning to be seen in some countries, such as Japan.