We are living through the dawn of a new epoch in the Earth’s history – the Anthropocene.

Humans have always shaped aspects of their environment, from fire to farming. But the influence of Homo sapiens on Earth has reached such a level that it now defines current geological time.

From air pollution in the upper atmosphere to fragments of plastic at the bottom of the ocean, it’s near impossible to find a place on our planet that humankind has not touched in some way. But there’s a dark cloud on the horizon.

Read more about extinction:

- Mass extinction: can we stop it?

- Has an animal ever evolved inself into extinction?

- Were birds the only dinosaurs to survive extinction?

Well over 99 per cent of the species that have ever existed on Earth have died out, most during cataclysms and extinction events of the sort that killed off the dinosaurs.

Humanity has never faced an event of that magnitude, but sooner or later we will.

The end of humanity is inevitable

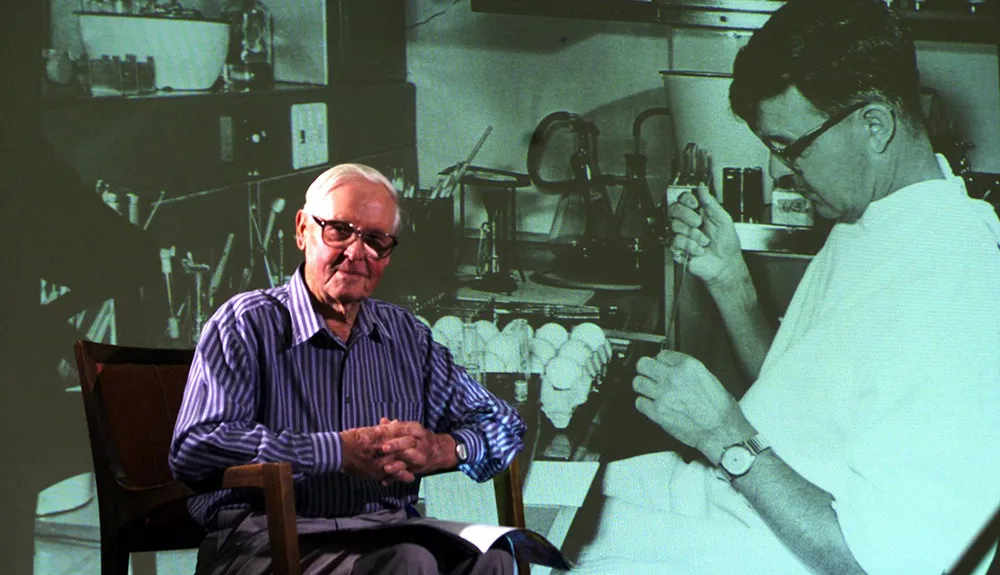

Human extinction, many experts believe, is not a matter of ‘if’, but ‘when’. And some think it will come sooner rather than later. In 2010, eminent Australian virologist Frank Fenner claimed that humans will probably be extinct in the next century thanks to overpopulation, environmental destruction and climate change.

Of course, the Earth can and will survive just fine without us. Life will persist, and the marks we’ve left on the planet will fade faster than you might think. Our cities will crumble, our fields will overgrow and our bridges will fall.

“Nature will break down everything eventually,” says Alan Weisman, author of the 2007 book The World Without Us, which examines what would happen if humans vanished from the planet. “If it can’t break stuff down, it eventually buries it.”

Before too long, all that will remain of humanity will be a thin layer of plastic, radioactive isotopes and chicken bones – we kill 60 billion chickens per year – in the fossil record. For evidence of this, we can look to areas of the planet that we’ve been forced to vacate.

In the 19-mile exclusion zone surrounding the Chernobyl power plant in Ukraine, which was severely contaminated following the 1986 reactor meltdown, plants and animals are thriving in ways they never did before.

A 2015 study funded by the Natural Environment Research Council found “abundant wildlife populations” in the zone, suggesting that humans are far more of a threat to the local flora and fauna than 30 years of chronic radiation exposure.

The speed at which nature reclaims a landscape depends a lot on the climate of an area.In the deserts of the Middle East, ruins from thousands of years ago are still visible – but the same can’t be said of cities only a few hundred years old in tropical forests.

In 1542, when Europeans first saw the rainforests of Brazil, they reported cities, roads and fields along the banks of major rivers. After the population was decimated by diseases that the explorers brought with them, however, these cities were quickly reclaimed by the jungle. The ruins of Las Vegas are certain to persist far longer than those of Mumbai.

Only now do deforestation and remote sensing techniques offer us a glimpse of what came before.

Plant and animal species that have formed close bonds with humanity are the most likely to suffer if we disappear.

The crops that feed the world, reliant as they are on regular applications of pesticides and fertilisers, would swiftly be replaced by their wild forebears.

“They’re going to get outcompeted, fast,” says Weisman. “Carrots will turn back into Queen Anne’s lace, corn may go back into teosinte – the original ear of corn that wasn’t much bigger than a sprig of wheat.”

The sudden disappearance of pesticides will also mean a population explosion for bugs.

Insects are mobile, reproduce quickly and live in almost any environment, making them a highly successful class of species, even when humans are actively trying to suppress them.

“They can mutate and adapt faster than anything else on the planet except for maybe microbes,” explains Weisman. “Anything that looks delicious is going to get devoured.”

The bug explosion will in turn will fuel a population increase in bug-eating species, like birds, rodents, reptiles, bats and arachnids, and then a boom in the species that eat those animals, and so on all the way up the food chain.

But what goes up must come down – those huge populations will be unsustainable in the long term once the food that humans left behind has been consumed.

The reverberations throughout the food web caused by the disappearance of humankind may still be visible as much as 100 years into the future, before things settle down into a new normal.

Some wilder breeds of cows or sheep could survive, but most have been bred into slow and docile eating machines that will die off in huge numbers.

“I think they will be very quick pickings for these feral carnivores or wild carnivores that are going to start proliferating,” says Weisman.

Those carnivores will include human pets, more likely cats than dogs. “I think that wolves are going to be very successful and they’re going to outcompete the hell out of dogs,” Weisman says.

“Cats are a very successful non-native species all over the world. Everywhere they go they thrive.”

The question of whether ‘intelligent’ life could evolve again is harder to answer. One theory holds that intelligence evolved because it helped our early ancestors survive environmental shocks.

Another is that intelligence helps individuals to survive and reproduce in large social groups.

A third is that intelligence is merely an indicator of healthy genes. All three scenarios could plausibly occur again in a post-human world.

“The next biggest brain in the primates per bodyweight is the baboon’s, and you could say that they’re the most likely candidate,” says Weisman.

“They live in forests but they’ve also learned to live on forest edges. They can gather food in savannahs really well, they know how to band together against predators. Baboons could do what we did, but on the other hand I don’t see any motivation for them. Life is really good for them the way it is.”

The future of life on a polluted planet

The shocks that could drive baboons (or other species) out of their comfort zone could be set in motion by the disappearance of humans.

Even if we all vanished tomorrow, the greenhouse gases we’ve pumped into the atmosphere will take tens of thousands of years to return to pre-industrial levels.

Some scientists believe that we’ve already passed crucial tipping points – in the polar regions particularly – that will accelerate climate change even if we never emit another molecule of CO2. Then there’s the issue of the world’s nuclear plants.

The evidence from Chernobyl suggests that ecosystems can bounce back from radiation releases, but there are about 450 nuclear reactors around the world that will start to melt down as soon as the fuel runs out in the emergency generators that supply them with coolant.

There’s just no way of knowing how such an enormous, abrupt release of radioactive material into the atmosphere might affect the planet’s ecosystems.

And that’s before we start to consider other sources of pollution.

The decades following human extinction will be pockmarked by devastating oil spills, chemical leaks and explosions of varying sizes – all ticking time bombs that humanity has left behind. Some of those events could lead to fires that may burn for decades.

Below the town of Centralia in Pennsylvania, a seam of coal has been burning since at least 1962, forcing the evacuation of the local population and the demolition of the town.

Today, the area appears as a meadow with paved streets running through it and plumes of smoke and carbon monoxide emerging from below. Nature has reclaimed the surface.

The final traces of humanity

But some traces of humankind will remain, even tens of millions of years after our end. Microbes will have time to evolve to consume the plastic we’ve left behind.

Roads and ruins will be visible for many thousands of years (Roman concrete is still identifiable 2,000 years later) but will eventually be buried or broken up by natural forces.

It feels reassuring that our art will be some of the last evidence that we existed. Ceramics, bronze statues and monuments like Mount Rushmore will be among our most enduring legacies.

Read more about Earth after humans:

- Life finds a way: when nature reclaims abandoned places

- Chernobyl: Has the area recovered since 1986’s nuclear disaster?

Our broadcasts, too: Earth has been transmitting its culture over electromagnetic waves for over 100 years, and those waves have passed out into space.

So 100 light-years away, with a large enough antenna, you’d be able to pick up a recording of famous opera singers in New York – the first public radio broadcast, in 1910.

Those waves will persist in recognisable form for a few million years, travelling further and further from Earth, until they eventually become so weak they’re indistinguishable from the background noise of space.

But even radio waves will be outlived by our spacecraft.

The Voyager probes, launched in 1977, are whizzing out of the Solar System at a speed of almost 60,000km/hour.

As long as they don’t hit anything, which is pretty unlikely (space is very empty), then they’ll outlive Earth’s fatal encounter with an inflating Sun in 7.5 billion years.

They will be the last remaining legacy of humankind, spiralling forever out into the inky blackness of the Universe.

- This article first appeared inissue 304ofBBC Science Focus–find out how to subscribe here