Throughout human history, the nefarious mosquito has been our number one killer and enemy, and although in recent years our counterattack – led by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation among others – have reduced her yearly carnage (only females bite), since 2000, the annual average number of human deaths caused by the mosquito has hovered upwards of 2 million. In context, deaths caused by other humans come in a distant second at 475,000.

Initially posited by Nobel Prize winning polymath (medicine, genetics, and mathematics), Dr Baruch Blumberg, and subsequently refined by other investigators, statistical extrapolation and estimates suggest that mosquito-borne disease, principally malaria, may be responsible for the deaths of approximately half of the roughly 108 billion humans that have ever lived.

Flying solo, untethered from a pathogen, the more than 100 trillion mosquitoes patrolling every pocket of our planet (save Antarctica, Iceland, and a handful of micro-islands) would be harmless. To ensure the survival of her species, she simply needs the blood of humans, and a zoological Noah’s Ark of other animals, to grow and mature her eggs.

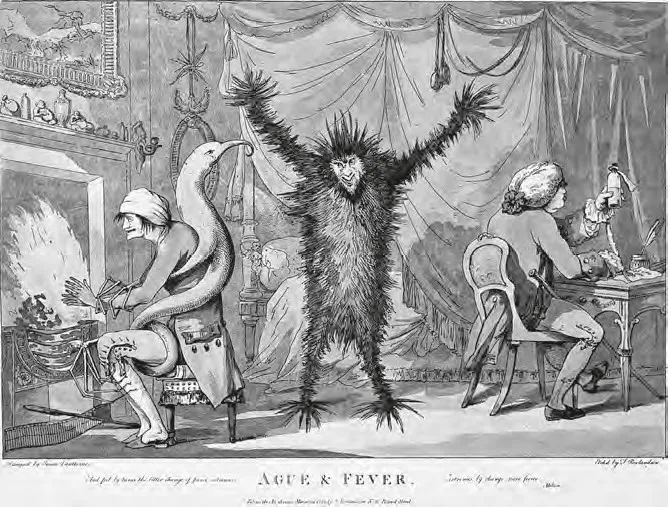

It is the catalogue of viruses, worms, and parasites that hitch a free reproductive ride through her bite that cause a merry-go-round of disease, misery, and death. Imagine a world without deadly mosquitoes. Our history and the world we know, or think we know, would be unrecognisable.

Here are just five ways in which the humble mosquito steered the course of human history:

1

Mosquitoes were essential to American independence

General George Washington’s greatest asset in the American Revolution was the malarious Anopheles mosquito, sapping the combat effectiveness of “unseasoned” British forces commanded by General Charles Cornwallis during the final southern campaign.

By the autumn of 1780, a fever-soaked Cornwallis reported that his regiments were crippled by malaria and were “so totally demolished by sickness [and] will not be fit for actual service for some months.”

In the spring of 1781, he marched the bulk of his ailing army north toward Virginia “to preserve the troops, from the fatal sickness, which so nearly ruined the army last autumn.”

By August, British forces retreated to Yorktown, situated along the estuaries and wetlands of the James and York Rivers. It was both prime mosquito country and the peak time of year for Washington’s Anopheles ally to attack.

Read more about how we're treating malaria:

- Could mosquitoes deliver malaria vaccines?

- Genetically engineered mushrooms used to kill malaria-carrying mosquitoes

- Could sleeping with chickens ward off mosquito-borne malaria?

At the outset of the siege of Yorktown on 28 September, Cornwallis commanded 8,700 men. By the time of his official surrender on 19 October he had 3,200 men fit for duty (only 37 per cent of his original number), with over half of his total force too sick to fight.

Cornwallis credited his final capitulation not to the enemy but to malaria: “I have been forced to give up the post…The troops being much weakened by sickness…Our numbers had been diminished by the Enemy’s fire, but particularly by Sickness…Our force diminished daily by sickness.”

The commander of the Hessian mercenaries, holed up in Yorktown with Cornwallis, reported two days before the surrender that the British were “nearly all plagued with fever. The army melted away…among whom not a thousand men could be called healthy.”

Yorktown’s famished mosquitoes forced the British surrender and redirected the flight path of history. Acclaimed historian J.R. McNeill emphasises that “Yorktown and its mosquitoes ended British hopes and decided the American war,” while saluting the tiny female Anopheles, who “stands tall among the founding mothers of the United States.”

2

Mosquitoes played a role in the creation of British colonial Australia

The British outpost of Australia was a by-product of both Yorktown and the mosquito.

In the decades preceding the American Revolution, the American colonies received an annual import of 2,000 British convicts (totaling roughly 60,000). With American independence, British Parliament was forced to consider an alternative station to unload a swelling number of domestic felons.

The fledgling colony of the Gambia was originally considered, but it was deemed that exile to Africa amounted to nothing more than a death sentence. Within one year of arrival, 80 per cent of the European diaspora perished from mosquito-borne disease.

This defeated the dual purpose of a penal colony: to punish and rid the mother country of criminals, while using these banished British subjects as the vanguard of colonisation.

By contrast the Australian continent was free (for the time being) of mosquito-borne diseases. The first British convicts arrived at the substitute destination of Botany Bay (Sydney) in January of 1788.

3

Mosquitoes aided in the success of European colonial expansion

By the 17th Century, thanks to trade across the Atlantic Ocean between Europe, Africa and the Americas, Old World powers were armed with an antimalarial derived from the bark of the South American cinchona tree.

Quinine powder permitted a small but stable European population to prosper in the tropics and secure fragile footholds in colonial outposts such as India (with its quinine laced gin and tonic), the East Indies, and Africa.

The real reason that European colonisers displaced or destroyed indigenous peoples, however, was more a matter of disease and differing immunities than of soldierly conquest. Europeans began their global push with the advantage and assistance of their contagions. Europeans had the benefit of acquired immunity, having long been exposed to their own infections. They simply carried their germs with them.

Later, the disease vectoring Aedes species (yellow fever, dengue, West Nile, Zika, chikungunya, and other encephalitides) were stowaways aboard ships shuttling slaves from Africa to the Americas.

Malaria, yellow fever, and dengue were transported in the boiling blood of disembarking European explorers, settlers, and their African slaves (many of whom possessed hereditary genetic shields to malaria increasing their demand as profitable plantation labourers).

Domestic Anopheles mosquitoes in the Americas promptly began vectoring the malaria parasite to unsuspecting indigenous populations. These disease-laden mosquitoes, along with other pathogens including smallpox and tuberculosis, paved the way for global European colonisation and domination in the centuries following Columbus by cutting a swath through indigenous populations.

Of the estimated 100 million indigenous inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere in 1492, a population of roughly 5 million remained by 1800.

4

Mosquitoes were instrumental in the Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire

Rome had a powerful ally inhabiting the 310 square miles of the Pontine Marshes surrounding and safeguarding the capital itself. The marshes were home to legions of lethal mosquitoes.

According to a vivid description from an early Roman scholar, the Pontine “creates fear and horror. Before entering it you cover your neck and face well before the swarms of large bloodsucking insects are waiting for you in this great heat of summer, between the shade of the leaves, like animals thinking intently about their prey.”

Successive invading armies including the Carthaginians, Visigoths, Huns, and Vandals were literally swarmed to death in marshes described by Florence Nightingale as the “Valley of the Shadow of Death.” (Mussolini successfully drained the wetlands prior to the Second World War. The Nazis purposefully reflooded the marshes and reintroduced malarious mosquitoes as a premeditated biological weapon against Allied troops at Anzio).

“In the Roman Empire, the revenge exacted by nature was grim. The prime agent of reprisal was malaria.” stresses historian Kyle Harper. “Malaria was an albatross on Roman civilization…and made the eternal city a malarial bog. Malaria was a viscous killer in town and country.”

Eventually, endemic malaria began to tap into and bleed the vitality and vigor of Rome, undermining its labour capital and military capacities. This malarial snowball effect facilitated the gradual decline and ultimate fall of the Roman Empire.

5

The mosquito caused widespread stagnation of southern economies around the world

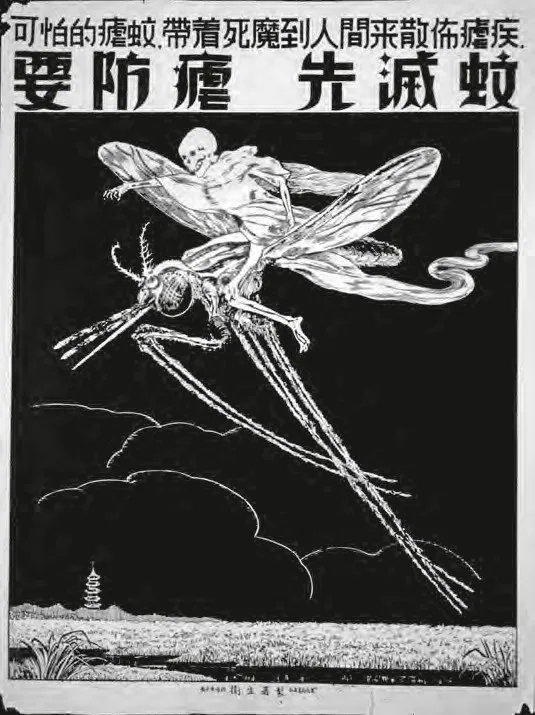

Ssu-ma Ch’ien, writing in 94 BCE, confirms that “in the area south of the Yangtze the land is low and the climate humid; adult males die young.” Accordingly, in ancient China, men traveling to the malarious south arranged for their wives’ remarriage before departing.

Award-winning historian William H. McNeill reveals that mosquito-borne dengue also plagued southern China: “Like malaria, dengue fever may have been present from time immemorial, lying in wait for immigrants from more northerly climes.” Such afflictions, he concludes, were “probably among the major obstacles to Chinese penetration southwards.”

This unequal burden of disease plagued economic development in southern China for centuries, leaving it stagnant and lagging far behind the prosperous north. The commercial disparity between north and south imparted by endemic malaria was mirrored in other countries, including Italy, Spain, and the United States (which was also awash with yellow fever epidemics), and was often referred to as the “Southern Problem.”

Malaria, according to an early-20th-Century Italian politician, “has the most serious social consequences. Fever destroys the capacity to work, annihilates energy, and renders a people sluggish and indifferent. Inevitably, therefore, malaria stunts productivity, wealth and well-being.”

In part, the mosquito’s uneven geographic economic impact would eventually engulf the United States in the momentous issues of slavery and civil war.

The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator by Timothy C. Winegard is out now (£12.99, Text Publishing)

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard