Throwaway living took off in the second half of the 20th Century. Disposable coffee cups, plastic stirrers and parties where all the plates could be tossed in the bin ‘improved’ our lives. Global plastic production soared from 1.5 million tonnes in 1950 to nearly 200 million tonnes in 2002. Today, it’s reached the 300 million tonne mark andis growing by 20 million metric tonnes a year.

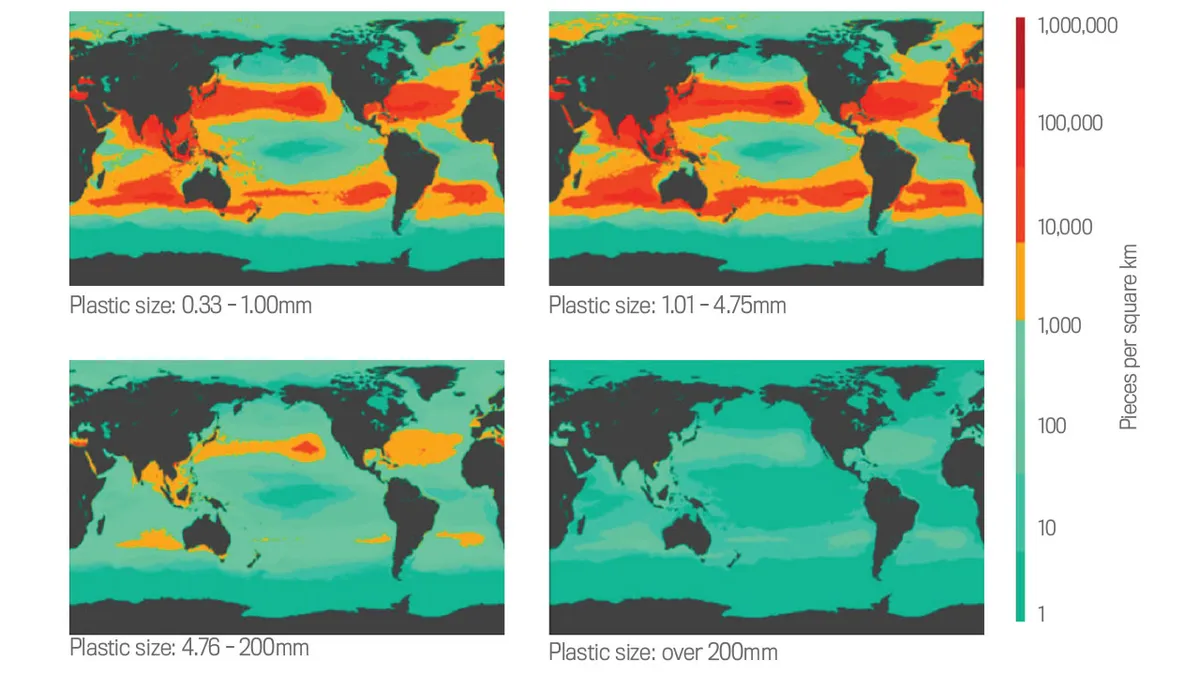

Reports of ocean garbage patches suggest that much of that plastic eventually ends up in our seas. But the reality is much worse, says Marcus Eriksen, one of the co-founders of 5 Gyres, the organisation that studies plastic pollution in the seas. “We should look at these not as garbage patches, but as clouds of microplastics in the world’s oceans,” he says.

Microplastics is the technical term for tiny pieces of plastic. These are the remnants of throwaway living that have leaked into every ocean. Take a boat out far enough and you’ll witness – as Eriksen has – bottles, toy figurines, roller balls from underarm deodorants and thousands of plastic sandals all floating around in the sea. But microplastics are so finely shredded by ocean currents that they’re impossible to spot from a boat and are easily mistaken for food by sea creatures.

One of Eriksen’s studies, published in December 2014, suggests that at least five trillion pieces of plastic, altogether weighing in at over 268,000 tonnes, are floating around near the surface of the sea. An incredible 92 per cent of the pieces are microplastics.

But these numbers don’t tally with the volume of plastic we’re producing. A second study published a week later explains why. While a lot of plastic initially floats, it soon gets clogged up with various kinds of gunk and ends up sinking to the seafloor. Just one handful of deep-sea sediment could contain up to 40 pieces of microplastic. At depth, this stuff is difficult to reach, let alone clean up. Which leaves us with one question: what are we going to do about it?

All at sea

A project called The Ocean Cleanup has been testing floating platforms for collecting bigger bits of plastic, but their own feasibility study suggests they cannot deal with microplastics. According to Eriksen, we’ll have to live with what’s already out there. “It’s going to sink, it’s going to get buried, it’s going to fossilise,” he says. “There’s no efficient means to clean up 5km down on the ocean floor.”

No one really knows what damage all that stranded microplastic is doing, but the hope is that once it’s mixed up with the sediment, it’s doing less of it. Yet the clouds of microplastics swirling in the water column pose a problem. The debris is easy for marine life to swallow, but the gunk that the plastics collect – such as pollution and bacteria – are also a threat. Plastics could be accelerating the passage of toxic chemicals into the food chain.

In May 2014, chemist Alexandra Ter Halle joined the 7th Continent Expeditionto the north Atlantic Ocean with the aim of analysing the gunk. After two days at sea, the boat was surrounded by thousands of small pieces of plastic. Ter Halle collected samples and is now analysing her data back at Paul Sabatier University in Toulouse, France. She is trying to work out why some plastics attract pollution as they age. “The difficulty lies in the fact that there are so many plastics, of different colours, shapes and compositions,” she says. “It’s difficult to extract a trend from all those pieces.”

The various types of plastic aren’t just a dilemma for scientists; they’re also problematic for consumers and recyclers. How many times have you wondered into which box to put a plastic lid or some flimsy bit of packaging, then ended up trashing it because you weren’t sure?

Nothing new

Ter Halle agrees there’s no easy way of cleaning up the existing mess. The answer, instead, is prevention. She says that switching to biodegradable plastics could offer part of that solution. While the first generation of biodegradables just broke down into smaller pieces, the second generation may have some utility. Ter Halle suggests that they could, for instance, be handy for shopping bags.

Yet Prof Richard Thompson, a marine biologist at Plymouth University, believes that the very notion of biodegradable plastic is flawed. “The idea that you could build into a plastic some kind of magic so that it would fulfil its life in service without deteriorating and then, the minute it becomes an item of litter, it somehow rapidly and harmlessly degrades… it kind of seems like you’re aspiring towards the impossible,” he says. According to Thompson, another problem with biodegradable plastics is mixing them with other plastics as part of the recycling process. The lifespan of the final recycled product is shorter than a product containing no biodegradable plastic.

Closing the loop

Thompson is one of the authors of the second December 2014 study. Having uncovered the true extent of microplastic pollution in seafloor sediment, he wants to see an end to plastic entering the ocean.

So does he have an answer? In 2015 he attended a workshop in Portugal involving over 50 people from around Europe, including scientists, policymakers and industry types eager to offer ideas for solving the problem. But there was a shortage of cutting-edge solutions. “From my perspective, there was nothing new from any of the participants,” he says. “A range of solutions are known to us, but it’s more about translating that into action.”

One option is banning certain types of plastics for particular applications, such as the plastic microbeads used in facial scrubs and toothpastes. These tiny particles – often measuring less than 1mm – wash straight down the sink and are too small to be filtered out at the waterworks. Thompson and Eriksen are both in favour of this approach, with 5 Gyres supporting a Beat the Microbead campaign that was started by the Plastic Soup Foundation.

But it’s not enough. Eriksen says that industry has got to be made to take responsibility for the way it uses plastic. “Using it for single-use candy wrappers, [potato] chip bags or stir sticks is just not responsible,” he says. “What I suggest is that if the producer or manufacturer cannot guarantee very efficient recovery of their product, like with some redemption programme or coupon, it had better be environmentally harmless.”

To dramatically reduce the amount of plastic accumulating in the oceans, the ‘loop’ of producing and recycling plastics would have to become a closed one. This means that any material leaving the system as waste would enter it again as a renewable resource. All plastic products would need to be designed with an end-of-life care package. In short, solving the plastic problem in the oceans means solving plastic pollution, full stop.

Thompson gives the example of two empty plastic bottles in his office. Both are made from the same recyclable plastic, but one is worth at least six times less than the other, just because it is red. Clear plastic is far more valuable to a recycler, but manufacturers don’t think about this when they’re designing their products.

We’re still living the throwaway lifestyle we got excited about in the 1950s, but we have to make that our past.

This is an extract from issue 279 of BBC Focus magazine. Subscribe and get the latest issue delivered to your door.