The year 2020 is likely to live in our memories as the year COVID-19 brought the world to a standstill. Many are hesitant to hope for a more normal 2021, choosing to tentatively take life one day at a time as our future remains uncertain.

But what if we cast our eyes to how 2022 may look?

Although the world has experienced pandemics in the past, the closest example we have to a potential blueprint would be the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic, another coronavirus similar to COVID-19 that cost over 770 lives, largely in eastern Asia, during the early 2000s.

However, after complications cropped up in animal trials for a SARS vaccine, and the virus died out in humans, research funding dried up. Little progress was made into coronavirus vaccine research.

Now, with multiple COVID-19 vaccine candidates available and more on the horizon, life post-vaccine is imminent for those in countries that can afford it. The dangers of vaccine nationalism may mean that poorer countries will go unvaccinated until 2022, 2023 or even beyond, by which time the threat of new variants – given the opportunity to spread and potentially be resistant to current vaccines – is likely to grow.

Read more about COVID-19:

- Life will not 'go back to normal' until at least half the population is vaccinated

- Ventilation and viral loads: the key misunderstandings of how coronavirus spreads

Although Moderna have confirmed their vaccine is still effective against the new variants that have emerged so far, this news will make little immediate difference to the Global South, as all of the company’s vaccines for 2021 have been bought up by richer countries.

Despite the vaccines preventing severe disease, it is still left to be seen if they reduce transmission and how long immunity will last; some believe annual vaccinations may be necessary. So for those who cannot be vaccinated and who exhibit different responses to illness, ongoing research into multiple therapeutics such as antivirals and antibodies could be life-saving.

While we know our bodies are capable of some immune response to the virus, assuming that we will eventually ‘get used’ to COVID-19 will continue to be a deadly gamble –not dissimilar to the ‘herd immunity without vaccination’ suggestions that prevailed early in the pandemic and proved to be harmful.

Likewise, going forward we need to be mindful not to fall into the trap of underestimating what we don’t know. While there are other human coronaviruses that cause colds, a comparison with COVID-19 seems unhelpful as research has shown COVID-19 infects both the upper and lower respiratory tract.

Read the latest coronavirus news:

- You may need to vaccinate your pets against COVID-19, scientists warn

- What coronavirus variants are in the UK?

- COVID-19 vaccine rollout may not achieve herd immunity amid new variants, research suggests

Also, whereas life often returns to normal after recovering from a cold or the flu, the ‘long-COVID’ phenomenon has seen many continue to suffer several months after infection with multiple organ damage, fatigue, muscle aches and difficulty breathing. Even 15 years after the SARS outbreak, a follow-up study found that many are still experiencing reduced lung-diffusion capacity.

To reduce the number of strains emerging, a zero-COVID strategy is the best course of action: by limiting community transmission. Even if a more harmful strain were to then evolve, it would eventually die out – as SARS did in the early 2000s.

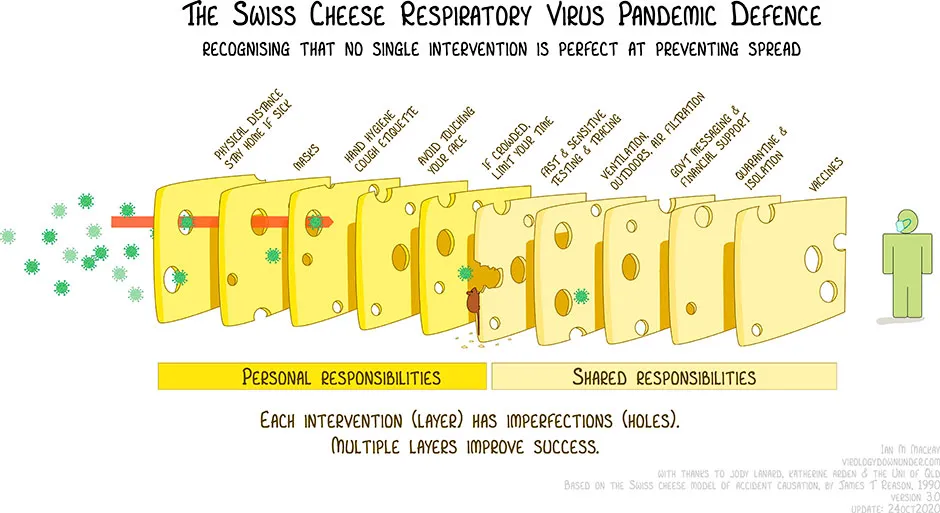

This can be achieved through a cocktail of interventions, best known as the ‘Swiss cheese analogy’: for example maintaining hand hygiene, mask-wearing, a functioning test-trace-isolate system, government support such as financial remittance during quarantine and restrictive measures that hinder social gatherings. If one intervention equates to a slice of cheese, while each intervention has imperfect holes, the more layers there are, the better the protection.

It may be that as the situation becomes more controlled, there will slowly be a re-introduction into shared indoor spaces like offices through hybrid working. How much we limit community spread is what will determine if COVID-19 will continue to circulate, like colds, flu and tummy bugs – only more dangerous.

Our next challenge becomes one of logistics, careful planning and whether equitable access to countries unable to afford it for their most vulnerable will be championed.

However, the progress we have made in one year since the World Health Organization’s declaration of COVID-19 as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern has been remarkable. Rapid genome sequencing, scientific investigation and multiple vaccine candidates mean elimination is possible.

So what state will the world be in a year from now? That is up to us: as individuals, as government leaders and as a global society.

Visit the BBC's Reality Check website at bit.ly/reality_check_ or follow them on Twitter@BBCRealityCheck