As more than one million people in the UK suffer with long COVID, scientists are scrambling to understand the long-term impacts of COVID-19 disease. While much is still unknown, researchers are starting to uncover possible mechanisms, how to treat long COVID, and why some people get it and others are immune. Latest figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) say 1.3 million people were experiencing self-reported long COVID as of 2 January 2022.

However, some say there may be many more long COVID sufferers in the UK than reported. One study by researchers in Norway suggests that 60 per cent of those with COVID-19 had persistent symptoms six months later.

We spoke to Dr David Strain, a lecturer at the University of Exeter Medical School and medical advisor for Action for ME, a charity supporting patients with a similar post-viral illness, myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME). He explained everything science currently knows about long COVID.

What is long COVID-19?

Strain says there is no textbook definition for long COVID, and the term can be used to refer to two separate conditions.

One is known medically as 'ongoing symptomatic COVID' and it occurs from week 4 after catching COVID-19, to week 12. "That's where your symptoms of COVID-19 disease are continuing beyond that initial acute phase," said Strain.

Then there's 'post-acute COVID syndrome' which is typically from 12 weeks onwards. However, these cut-off time frames are beginning to fall away, as many patients across both types use the term long COVID.

What causes long COVID?

There are several theories as to how the SARS-CoV-2 virus causes long-lasting symptoms, but the mechanism is likely to be different depending on how a patient's long COVID presents, said Strain.

In those who are hospitalised with COVID-19-induced pneumonia, or spend time in the intensive therapy unit (ITU), Strain explained that this may in itself cause long COVID.

"Any pneumonia that puts you in the hospital ITU for a few weeks will leave you with symptoms for quite some time," said Strain.

Some long COVID patients will have damage to their blood vessels, caused by the coronavirus.

"Unlike most other lung viruses, COVID-19 has a real preference for affecting your blood vessels," said Strain. "So, we can see small clots appearing. If they affect the lungs, you get what's called a pulmonary embolism. If the clots affects the kidneys, you can get kidney disease. If it affects your brain, you get strokes."

However, some long COVID patients were never in ITU, and don't have any blood vessel damage. For this group, it's harder to know why they have persistent symptoms.

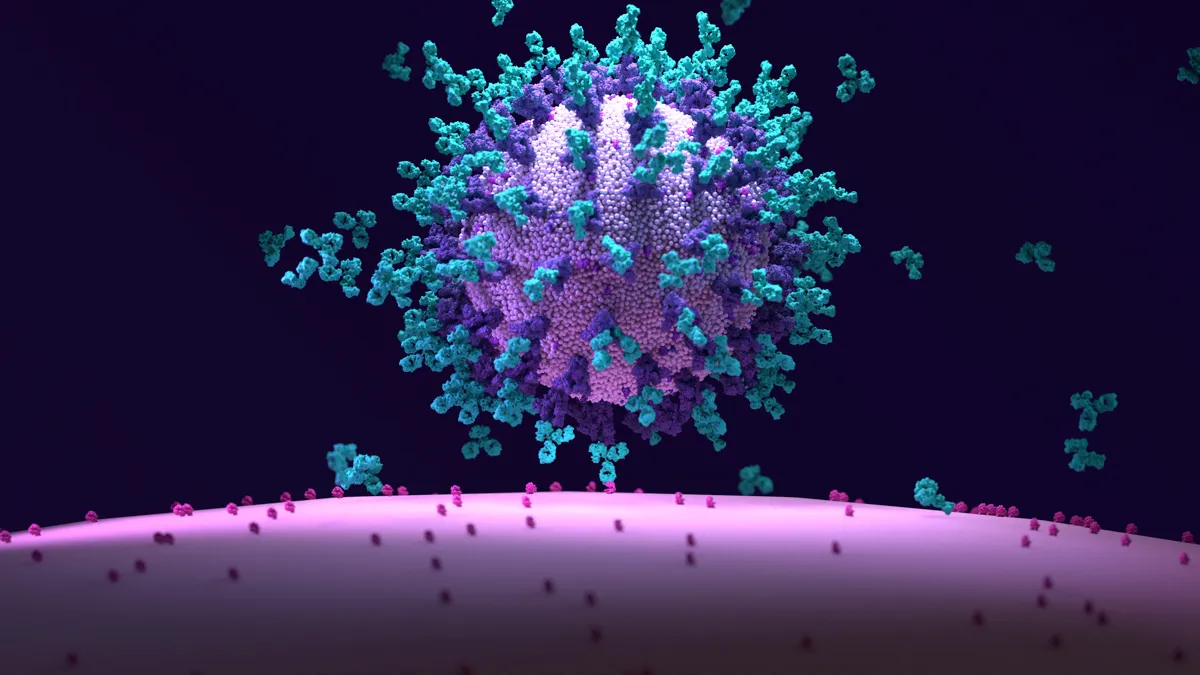

One theory relates to the path that COVID-19 takes to get into our bodies. All viruses have a way to get into our cells, but COVID-19 uses an entry point that is part of our body's defence system. Making it inactive could lead to long-term effects.

All viruses have to use a pathway to get into cells, and COVID-19 uses an enzyme called ACE2.

"If you have any source of infection in your body, your body flushes essentially a poison through the system and it gives your own cells the antidote to that poison. Then anything that's not 'you' gets poisoned. But it's the ACE2 enzyme that creates your antidote."

It could be that when COVID-19 impairs ACE2, our bodies are flooded with poison designed to rid us of the disease, but our inability to make the antidote leads us to develop long COVID.

Another possible cause of long COVID could be the presence of the virus in our bodies long after we've tested negative for COVID-19.

"Some researchers are asking whether there could be some virus hiding somewhere in the body in an immuno-privileged tissue, a place that your immune system can't get to," said Strain.

Strain believes the most likely place a virus could hide would be in our guts. Our gut isn't generally affected by our immune system, because there are good and bad bacteria and virus that live there to make up our microbiome.

"People who get long COVID do have a dramatic change in the make up of their microbiome. We see that, and it's useful to know because it means that we can start looking at that tissue to see if the gut the place where the problem is. Though it could be several things; it could be that the virus is living there. It could be that the virus just wipes out your healthy gut bacteria. Or, it could just be purely coincidental, and people have got long COVID have made diet changes because they're reaching for higher energy foods, and when your diet changes, so too does your bacteria change."

What are the symptoms of long COVID?

According to the January 2022 ONS data, the most common long COVID symptoms were fatigue, found in 50 per cent of patients; shortness of breath, reported by 37 per cent, and a loss of smell (37 per cent) and loss of taste (28 per cent).

The ferocity of the symptoms can vary, and Strain said there can be a waxing and waning of peoples' illnesses.

"Symptoms can vary from extreme, debilitating fatigue and malaise right through just some very mild symptoms. The classic symptoms that people are describing are fatigue, difficulty concentrating or what's called brain fog, and then muscle weakness or muscle aches and pains, which we call myalgia."

One aspect of long COVID is what's called post-exertional malaise, which Strain describes as the tiredness and lethargy that is completely disproportionate to the exercise or activity undertaken.

Read more about long COVID:

- Up to 20 per cent of coronavirus patients may develop long COVID

- 'Persistent' structural changes in lungs could explain long COVID

"That seems to be one of the hallmark features of the fatigue that people get. And the only place that we've seen that symptom before is in chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME. So much so that a lot of people are saying that this entire group of patients with long COVID basically have ME. Actually, a lot of people with ME are looking to long COVID research and saying maybe we'll finally start getting some answers."

Strain says that some people are also having symptoms such as hair loss, temperature changes, feeling feverish and diarrhoea.

"A significant proportion of people are describing anxiety or difficulty focusing. That's really difficult to tease out [a cause], because if you've had a very mild illness and then been left with a debilitating fatigue, it's understandable that you're going to be feeling depressed. You're effectively grieving for the fact that your body's not working three months later.

"But there are people who get disproportionate anxiety or neurological problems like mood alterations. Given that our mood is just a collection of neurones and hormones in the brain, there's no reason to suspect that the other dysregulations that are affecting the body aren't affecting the brain. Therefore, this is a manifestation of long COVID."

How do I know if I have long COVID?

The NHS recommends that people contact their GP if they are worried about any symptoms that have persisted for four weeks or more after having COVID-19.

While the symptoms of fatigue, muscle pain and shortness of breath are common in long COVID, they could be an indicator of an underlying illness.

"The main thing that we do in the clinic is make sure that there's nothing else [going on] that we do know how to treat. So, if we're getting people with severe palpitations, we start looking for other causes of palpitations or we try medications at work for palpitations. Some people actually have a syndrome called postural orthostatic tachycardia, for which we can test.

"We've actually picked up a few things in people who've come in for long COVID. A few patients who had under-active thyroid problems, a few new cases of diabetes or picked up. I saw one patient who actually had cancer and his haemoglobin had dropped, and that's why he was fatigued."

Is there a test for long COVID?

Currently, long COVID clinics test for other illnesses to rule out. However, scientists are looking for ways to test for specific damage associated with long COVID.

One study by researchers from universities across Cardiff, Manchester, Oxford, and Sheffield, showed that patients with long COVID seem to have problems with getting oxygen into their cells.

"Oxygen isn't getting across the membranes as it should, and that's something that hadn't been shown before in long COVID patients or in any other disease, really. That suggests that the oxygen from the air isn't getting into the blood vessels, and that raises a whole lot of questions about why. Is it because the membranes aren't right? Have the blood vessels become occluded or are they just not transmitting? Is it a problem with the blood itself?

"But the fact that they can identify that there is a problem is a step in the right direction."

Some are also looking to see if there is a problem with long COVID patients' metabolism.

Our body turns the food that we eat into a molecule called ATP, which is a store of energy that can be released when needed. As we exercise, or do anything that requires energy, we begin to break down ATP. It then becomes something called ADP and a molecule called phosphocreatine.

"Measuring the amount of phosphocreatine and its ratio to amount of ATP can give you an idea of where your metabolism is and whether you're drained," said Strain. "This is something that's already been demonstrated in people with ME."

Can asymptomatic people get long COVID?

While those with long COVID as a result of being in the hospital ITU or due to blood vessel damage will have had symptomatic COVID-19, figures show that long COVID patients with predominantly ME-like symptoms might have had very mild, or even asymptomatic COVID-19.

"Very often, the only time that these patients realise they've had COVID is because they get antibody tests come back positive," said Strain.

How does the vaccine affect my chances of getting long COVID?

Studies have shown that getting the COVID vaccine lowers the chance of developing long COVID.

January data from the ONS suggests that having two doses of the vaccine at least two weeks prior to catching COVID-19 decreased the odds of a person reporting long COVID by 41 per cent.

This could suggest that long COVID could have an immunological aspect, that is either treated or at least helped by the vaccine. Strain says there could be individuals who might have got long COVID if it hadn't been for the boost of immunity offered by the vaccine.

In one study that Strain was involved in, they found that the majority of people (60 per cent) who had long COVID symptoms actually got better when they were vaccinated.

How long does long COVID last?

Scientists do not know exactly how long symptoms will last, but long COVID patients do get better.

"It's taken a long time, but there's a huge number of people who are getting better on their own. People are getting to a stage where they don't have symptoms anymore.

"For the true long-haulers, the ones who've had it for more than 12 months – and there's still about 600,000 of those – the greater the understanding of the disease, the more chance we've got for getting a cure. I think there's a lot of hope, not just for long COVID, but for other aligned diseases, because of the amount of research that's going into this. We've actually found out more about the condition in the last six months than we found out about ME in 30 years' worth of research."

Do we know how to treat long COVID?

Strain says that for long COVID patients with damaged blood vessels, these elements are very similar to other diseases and conditions whereby lots of blood clots form. So, these patients can be helped by the treatments already being used.

If long COVID symptoms are caused by a problem with a person's gut bacteria, this could also be treated using methods already known.

"There are treatments available to restructure your gut bacteria," said Strain. "We we already use them in patients who have are infected with a bacteria called Clostridium difficile. This is one particular bacteria runs throughout your entire colon, and it causes quite nasty diarrhoea. The treatment we use there is basically a faecal transplant, taking the [good] bugs out of one person and giving them to another."

Long COVID has also been identified in groups of people, and understanding why could point to future treatments.

"It does go in families, does go in teams, it does go in particular lifestyles. People can say, well, if your husband and daughter both get long COVID, then it could be genetic. And that's true. But that doesn't explain why husbands and wives are getting it.

"However, they are very likely to have similar gut bacteria because they have a similar diet, similar lifestyle, similar exposures. All of those things are suggestive that having healthy bacteria could be one of the one of the ways to protect yourself against long COVID, and it could even be a treatment in the future."

Strain stresses that it is unlikely that there will be a one-type-fits-all treatment. One large study called STIMULATE-ICP is due to be launched soon, and it will investigate several different types of treatment. The study will include anticoagulants, anti-inflammatories, antivirals, a structured exercise programme and an energy-management technique called pacing.

How can I recover from long COVID?

While many of the potential treatments are yet to be proven to be effective, the pacing technique can be a simple, straightforward option for people to take at home.

"Pacing is actually is quite simple. Let's say you can walk 1,000 yards, and that's the point that you start to feel fatigued. Then, you should never walk 1,000 yards. You should walk to 800 yards, then stop and have a rest.

"What you should really be doing is going out on a regular basis and only doing 80 per cent of the maximum you can do. What you'll soon find is your 80 per cent will gradually build up."

Using this method, people can at points re-evaluate their 80 per cent, meaning they might go up to 900 yards, then 1,000, then 1,100 and so on.

"Now, it takes longer to build up that way than say if you go beyond where your maximum is. But if you go beyond maximum, you end up with three or four days of recovery time afterwards. Although you would have pushed your fitness up by doing a little bit more at the time, your overall fitness level is taking a step down during your recovery."

Are people with long COVID still infectious?

No, not as far as we currently know.

Modelling from the UK Health Security Agency has shown that if people with COVID-19 have two consecutive negative rapid lateral flow results on the sixth day of their self-isolation period, ending their isolation early will equate to roughly 7 per cent being released still infectious. It is thought that people with long COVID, or post-COVID symptoms after four weeks or more, are no longer infectious.

About our expert

Dr David Strainis a senior clinical lecturer at the University of Exeter Medical School and a consultant for the Devon ME/CFS specialist service. During the pandemic he has been leading the British Medical Association’s COVID-19 response team.