There is expected to be a significant reduction in weekly supply of the COVID-19 vaccines starting at the end of March, with health leaders stating that volumes for first doses will be significantly reduced. But what does this mean for the vaccination programme?

Here are some of the answers to the key questions.

What is behind the delay?

It has been said that the reduction in vaccine supply is partly down to a delivery of five million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine from the Serum Institute of India being held up by four weeks.

However, indications from the Government are that a number of global manufacturers are experiencing issues with supply.

What does this mean for the vaccine rollout?

Health leaders in England have said that from 29 March volumes for first doses will be significantly constrained. This shortfall is predicted to last for four weeks.

Professor Martin Marshall, chairman of the Royal College of GPs said the focus in April will now be on giving second doses to people who were vaccinated earlier in the year.

The guidelines from the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation say there should be between 4 and 12 weeks between doses.

Read more about COVID-19:

- Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine and blood clots: Should we be worried?

- COVID-19: Can we stop the spread of more coronavirus variants?

What about the vaccination targets?

The Department of Health and Social Care says the Government is still on track to offer a first dose to all adults by the end of July.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock has also said the 15 April target for vaccinating over-50s will still be met.

Who does the delay affect?

People in their 40s are likely to have to wait until May to get their COVID-19 vaccine.

It had previously been hoped that vaccination of this group would start in April, after all of those over-50 had received their first jab.

What about the Moderna vaccine?

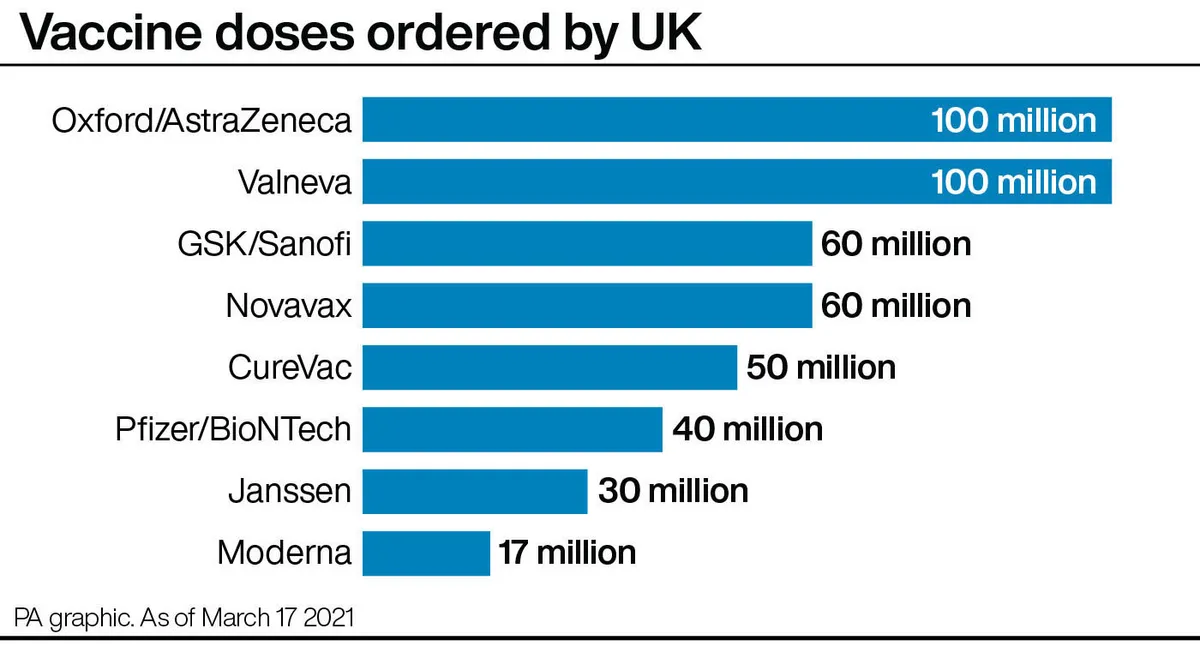

The jab from US biotech firm Moderna is not expected to arrive until the spring, although a specific date has not yet been given.

After the vaccine was approved by regulators in January, the Government purchased an additional 10 million doses of the vaccine on top of its previous order of 7 million.

How do scientists develop vaccines for new viruses?

Vaccines work by fooling our bodies into thinking that we’ve been infected by a virus. Our body mounts an immune response, and builds a memory of that virus which will enable us to fight it in the future.

Viruses and the immune system interact in complex ways, so there are many different approaches to developing an effective vaccine. The two most common types are inactivated vaccines (which use harmless viruses that have been ‘killed’, but which still activate the immune system), and attenuated vaccines (which use live viruses that have been modified so that they trigger an immune response without causing us harm).

A more recent development is recombinant vaccines, which involve genetically engineering a less harmful virus so that it includes a small part of the target virus. Our body launches an immune response to the carrier virus, but also to the target virus.

Over the past few years, this approach has been used to develop a vaccine (called rVSV-ZEBOV) against theEbola virus. It consists of a vesicular stomatitis animal virus (which causes flu-like symptoms in humans), engineered to have an outer protein of the Zaire strain of Ebola.

Vaccines go through a huge amount of testing to check that they are safe and effective, whether there are any side effects, and what dosage levels are suitable. It usually takes years before a vaccine is commercially available.

Sometimes this is too long, and the new Ebola vaccine is being administered under ‘compassionate use’ terms: it has yet to complete all its formal testing and paperwork, but has been shown to be safe and effective. Something similar may be possible if one of the many groups around the world working on a vaccine for the new strain ofcoronavirus(SARS-CoV-2) is successful.

Read more: