- A toxin released by a strain of the E. coli bacteria leaves the unique “fingerprints” of bowel cancer tumours.

- Detecting this specific DNA damage could, in future, allow doctors to identify people at higher risk of the disease.

- Finding suggests E. coli may contribute to 1 in 20 bowel cancer cases in the UK.

A common type of bacteria found in the gut may play a role in the development of bowel cancer, according to research.

Scientists have found a toxin released by a strain of the E. coli bacteria leaves unique patterns, or “fingerprints”, as it damages the DNA in the cells lining the gut.

These so-called fingerprints were observed mainly in bowel cancer tumours, showing “a direct link” between the microbial toxin and the genetic changes that contribute to cancer development.

The researchers suggested that detecting this specific DNA damage could, in future, allow doctors to identify people at higher risk of the disease.

Read the latest news about cancer discovery:

- Flashing blue lights switch on cancer-fighting cells

- Statins could reduce ovarian cancer risk by 40 per cent

- Cancer-causing mutations can appear decades before diagnosis, study suggests

Professor Hans Clevers, of the Hubrecht Institute in the Netherlands and one of the study authors, said: “Things like tobacco or UV light are known to cause specific patterns of DNA damage, and these fingerprints can tell us a lot about past exposures that may have caused cancer to start.

“But this is the first time we’ve seen such a distinctive pattern of DNA damage in bowel cancer, which has been caused by a bacterium that lives in our gut.”

The scientists investigated the role of gut microbiome, or the ecosystem of bacteria in the digestive system, in the development of bowel cancer.

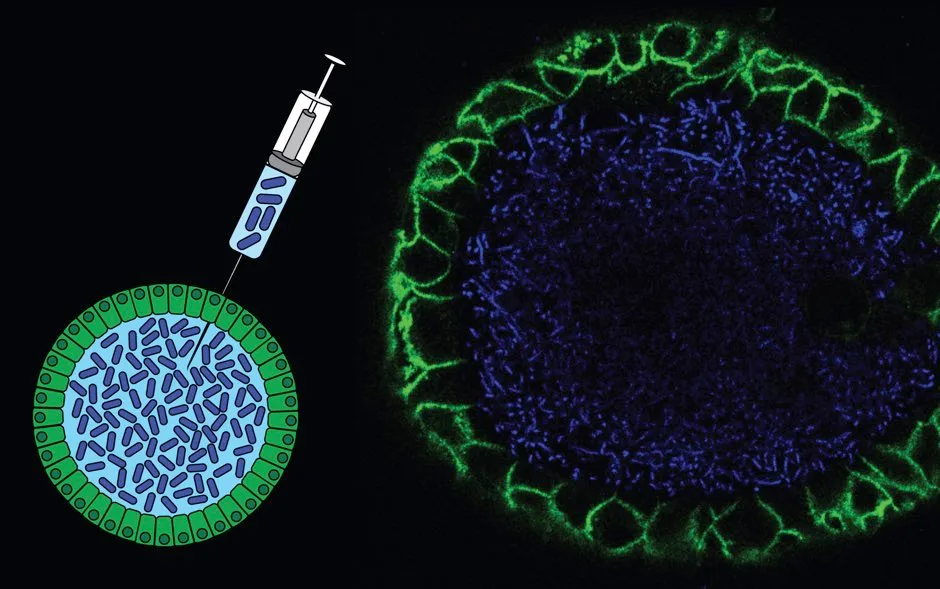

They focused on a strain of E. coli producing the toxin known as colibactin.

Miniature replicas of the gut grown in the lab were exposed to this toxin and the researchers found evidence of DNA damage following unique patterns.

The team analysed the DNA sequences of more than 5,500 tumour samples and found these fingerprints to be present more often in bowel cancers than other types of tumour.

The researchers then focused on bowel tumours specifically, looking at more than 2,000 samples collected as part of the 100,000 Genomes Project run by Genomics England.

They found the colibactin fingerprints were present in 4-5 per cent of the samples, which the researchers said suggests that colibactin-producing E. coli may contribute to 1 in 20 bowel cancer cases in the UK.

They are now looking at other bacteria and their toxins associated with bowel cancer as part of the next steps in their research.

Read more about the microbiome:

- 15 tips to boost your gut microbiome

- Psychobiotics: Your microbiome has the potential to improve your mental health, not just your gut health

- The British microbiome: how our guts can tell us more than our genes

Professor Philip Quirke, of the University of Leeds and study-co-author, said: “We hope to identify more DNA damage fingerprints to paint a better picture of risk factors.

“We will then need to work out how we can reduce the presence of high-risk bacteria in the gut.

“But this is all in the future, so for now people should continue to eat a healthy diet and participate in bowel cancer screening.”

There are around 42,000 new bowel cancer cases every year in the UK, where it remains the second most common cause of cancer death, according to Cancer Research UK.

The research, funded by a £20 million Cancer Research UK Grand Challenge award, is published in the journal Nature.

Q&A: Am I more bacteria than human?

There are more bacterial cells in your body than human cells, but the ratio isn’t as extreme as once thought. A 2016 study at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel found that our total cell count is 56 per cent bacteria (compared with earlier estimates of 90 per cent). And because bacteria are much smaller, their total mass is only about 200g. So by weight, we are more than 99.7 per cent human.

Even so, we shouldn’t underestimate the contribution bacteria make to our body, nor feel threatened by it. Most of our ‘human’ cells contain structures called mitochondria, which we rely on to convert glucose into compounds we can use for energy.

These mitochondria probably began as free-living bacteria before they embarked on a symbiotic relationship with us. The only reason that we don’t include them in our tally of bacteria is that they never leave the confines of human cell membranes, though they are, in many respects, independent organisms with their own DNA.

Like all multicellular animals, we can’t easily point to individual components and say “This is part of me, and this is not”. Your body is like a city – it has a collective identity that goes beyond its individual inhabitants. The pigeons and squirrels that call London home are just as much a part of it as the humans who live there.

Read more: