- The oceans' 'biological pump' is capturing even more carbon dioxide than previously thought, a study finds.

- Phytoplankton on the surface of the ocean absorb carbon dioxide, and are eaten by zooplankton, carrying theCO2 deeper into the ocean.

- The levels of CO2 in the atmosphere would be much higher if not for the biological carbon pump.

The “biological pump” in the world’s oceans, which plays a key part in the global carbon cycle, is capturing twice as much carbon as previously thought, scientists have said.

The biological carbon pump (BCP) contributes to the role of the ocean in taking up and storing carbon dioxide (CO2) by removing the gas from the atmosphere, changing it into living matter, and distributing it to the deeper ocean layers.Without the BCP, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 would be much higher.

Read more about the ocean:

- How we can save the oceans, and how they can save us

- Saving ocean life within a human generation is 'largely achievable' say scientists

The researchers said their findings, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could have implications for future climate assessments.

Single-celled organisms, called phytoplankton, live on the ocean’s surface and use sunlight to make food and energy – taking up CO2 and releasing oxygen in the process. When phytoplankton die, they are eaten by other marine creatures, like zooplankton.

And once these creatures die, they become biological debris, known as marine snow, that are rich in carbon and fall deeper into the ocean, a key process in the BCP. However, the phytoplankton’s ability to absorb CO2 depends on the amount of sunlight able to penetrate the ocean’s upper layer.

Researchers set out to measure the depth of the ocean’s sunlit surface area or euphotic zone, using a technique known as chlorophyll fluorescence detection that looks for the presence of photosynthetic phytoplankton in the deeper layers of the ocean.

Read more about climate change:

- The road to net zero: how we could become carbon neutral

- Tropical forests could switch from a carbon sink to a carbon source in the next 20 years

The found the depth of the euphotic zone, which is where most of the marine species live, to significantly vary throughout the world.

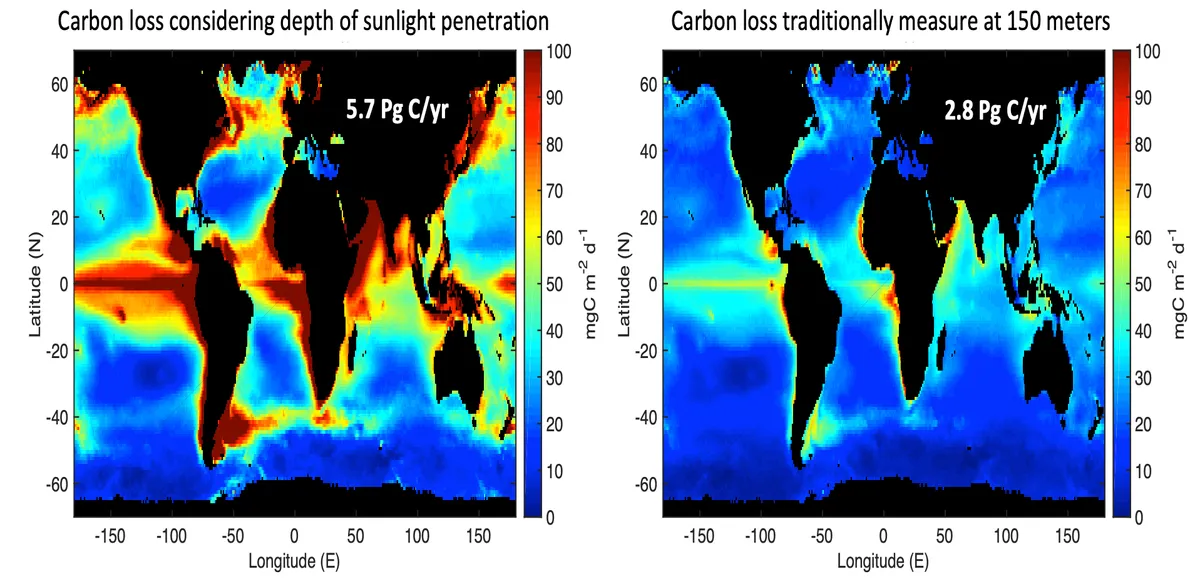

Combining their findings with data from previous studies of the BCP, the authors were able to estimate the rate at which carbon particles are sinking.They found that about twice as much carbon sinks into the ocean per year than previously estimated.

Study leader Dr Ken Buesseler, a geochemist with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, a US research institute dedicated to the study of marine science, said: “If you look at the same data in a new way, you get a very different view of the ocean’s role in processing carbon, hence its role in regulating climate.”

Researchers believe using their method to assess the BCP could lead to more accurate climate models that could help shape the global climate policy.

Dr Buesseler added: “Using the new metrics, we will be able to refine the models to not just tell us how the ocean looks today, but how it will look in the future. Is the amount of carbon sinking in the ocean going up or down? That number affects the climate of the world we live in.”

Reader Q&A: Do we really know what climate change will do to our planet?

Asked by: Jennifer Cowsill, via email

There is no doubt that greenhouse gas emissions caused by humans are changing our climate, resulting in a progressive rise in global average temperatures. The scientific consensus on this is comparable to the scientific consensus that smoking causes lung cancer.

Our climate is a hugely intricate system of interlinking processes, so forecasting exactly how this temperature increase will play out across the globe is a complex task. Scientists base their predictions on powerful computer models that combine our understanding of climatic processes with past climate data.

Many large-scale trends can now be calculated with a high degree of certainty: for instance, warmer temperatures will cause seawater to expand and glaciers to melt, resulting in higher sea levels and flooding. More localised predictions are often subject to greater uncertainty.

Read more: