Superstitious? Look away now; a Blue Moon is here tonight. And it’s a double whammy this month, because it’s also a supermoon.

Okay – so astronomically speaking, the Super Blue Moon this August won’t have any bearing on your life whatsoever, but it will be an impressive sight, nonetheless.

It’s the second full Moon of the month, and the third supermoon of the year, but when exactly can you see this rare Super Blue Moon? Which constellation will it appear in? And, what's the best time to view it from the UK? Answers to these questions, and more, are below.

Why not make the most of the last of the mild nights with our full Moon UK calendar and astronomy for beginners guide? And in case you missed it, veteran astronomer Pete Lawrence has put together a comprehensive guide to how to take great pictures of the Moon, even if you only have a smartphone.

When can I see the Blue Moon in 2023?

The Super Blue Moon will be visible tonight, 31 August 2023, in the UK and around the world. If you’re unable to see this rare supermoon at its peak, it will also appear full until 1 September 2023.

“The Moon is technically at opposition when it appears full as will be the case on 31 August at 2:36am BST,” says BBC The Sky at Night presenter and astronomer Pete Lawrence.

“This is the second full Moon in August, the first occurring on 1 August at 19:32 BST. Although not strictly correct, popular culture refers to the second full Moon in a month as a Blue Moon even though it’s unlikely to appear blue!”

You'll have to wait quite a while before the next full Super Blue Moon, which will be visible 31 January 2037.

When is the best time to see the Super Blue Moon?

The Super Blue Moon rises at 8:07pm in the east-southeast on 30 August 2023 (as seen from London, UK).

Syzygy, which happens for just a moment when the Earth, Moon and Sun are perfectly aligned (and the Moon is fully illuminated), will happen in the early morning of 31 August, at 1:36am.

The Sun will begin to set at 7:51pm on the 30th, and like a seesaw, the Moon will rise into the twilight sky and should offer a good view (clouds permitting) soon after rising.

If you live in an area with an unobstructed view of the eastern horizon, around 9pm will be a good time to meander to a window to spot this rare Moon. We’ll also be treated to the ‘moon effect’ around this time. This is when – to our human eyes – the Moon looks bigger when it’s closer to the horizon.

If you live in an area where the horizon is obstructed (for example, by trees, buildings, or hills), then you’ll still get a good view once the Moon has risen higher in the sky, around 11pm.

What is a Blue Moon?

The Blue Moon that occurs this month is what’s known as a ‘monthly blue Moon’, also known as a ‘Calendrical Blue Moon’.

This is where two full Moons occur within one calendar month. As the time between two full Moons is around 29.5 days, and because our Gregorian calendar has either 30 or 31-day-long months (mostly), it’s possible for another full Moon to occasionally make an appearance at the end of the month. And it’s this second full Moon that we call a Blue Moon.

Blue Moons are rare, hence the saying, “once in a blue moon”. They occur roughly once every two to three years, and the last Blue Moon to occur was Halloween, 31 October 2020.

There is also another, more traditional definition to a Blue Moon, and that is what’s known as a ‘seasonal Blue Moon’. According to NASA, a seasonal Blue Moon is the third Blue Moon in a season that has four full Moons.

Similarly, we sometimes get two new Moons in a month, and this extra new Moon is known as a black Moon.

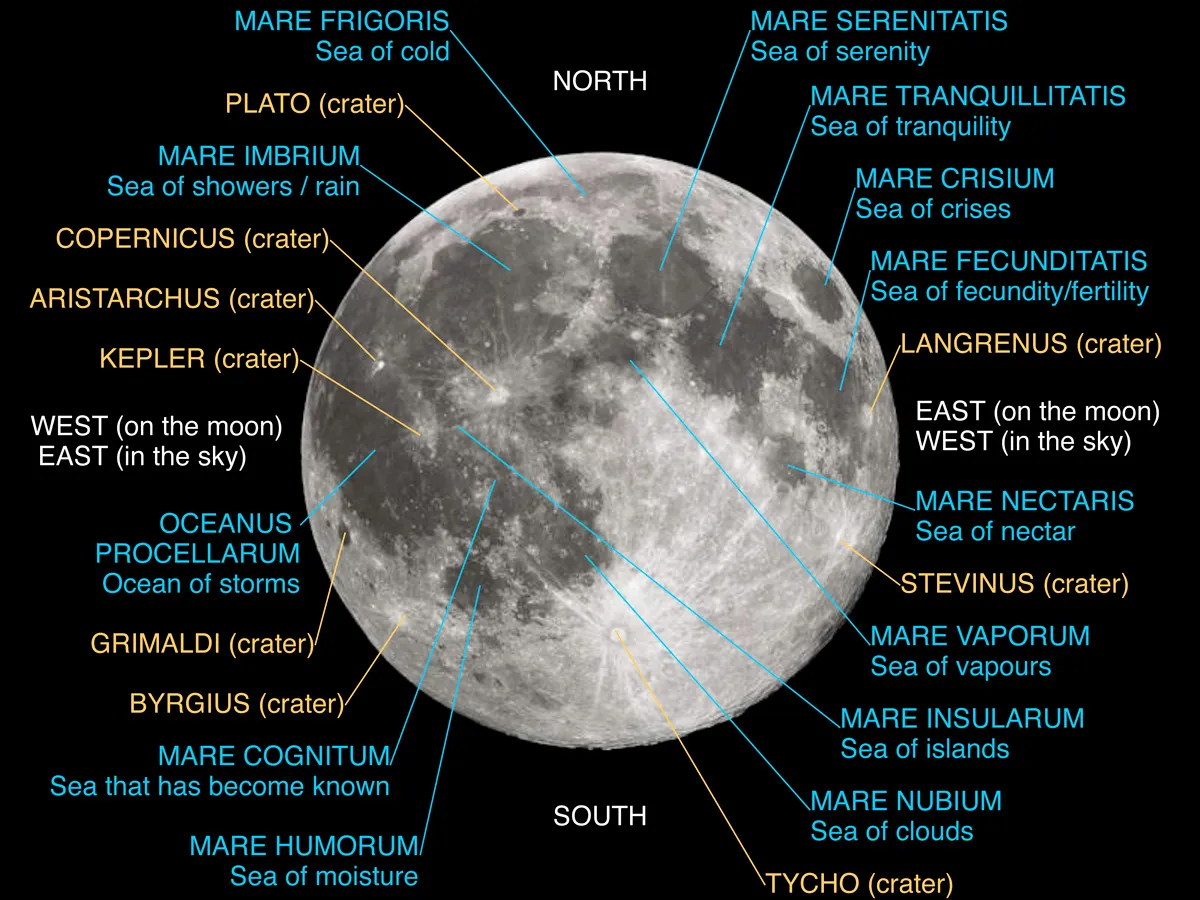

What can I see on the Moon?

A supermoon can offer a good opportunity to spot craters and dark volcanic areas with the naked eye. For the most prominent shadows, it’s actually better to try phases other than during a full Moon, although there are still some impressive features you can spot during the full phase.

Here are a few lunar features to look out for during tonight’s Super Blue Moon:

Tycho crater

Where: Southern uplands

One of the most distinctive craters on the Moon, the Tycho crater looks like a giant splash in the southern highlands. Although just 80km (53 miles) in diameter, its relative youth helps us distinguish it from the other craters on the lunar surface.

At a fresh 108 million years old, the splash marks, or ‘rays’ still stand out as bright streaks radiating out from the crater. In 1972 Apollo astronauts brought a sample from one of these rays back to Earth, so we have a pretty accurate idea of its age.

Oceanus Procellarum

Where: Western edge

From the Latin meaning ‘Ocean of Storms’, the Oceanus Procellarum is the largest of the lunar mares. To us, it looks like a huge dark patch on the western edge; but what we’re actually looking at is a vast volcanic plain.

Like the other mares (dark patches on the Moon), it’s basalt – made from the hardening of ancient magma. Spanning more than 2,500km (1,600 miles) and covering an area of approximately 4 million km2, it accounts for a whopping 10.5 per cent of the total lunar surface.

Copernicus crater

Where: Oceanus Procellarum, slightly northwest of the centre

Not to be confused with the Martian crater of the same name, this 93km (58 mile) diameter crater is located within the Oceanus Procellarum, and is around 3.8km (2.4 miles) deep.

It’s a nice target to try and pick out with binoculars, and although circular in shape, has a distinct hexagonal wiggle to the walls. In planetary terms, the Copernicus crater is also in its youth; between 800 million and 1 billion years old.

How to photograph the Super Blue Moon

Did you know you can take great pictures of the Super Blue Moon with just a smartphone? Okay – mobile phones have come a long way these days, and most boast excellent cameras, but there are a few easy hacks you can try to boost your lunar photography even further.

Snapping the supermoon just after rising, while the sky is not yet in total darkness, will enable you to capture some interesting foreground features (foliage, skylines, buildings etc) for a pleasing composition. You’ll also avoid overexposing the Moon, and with a steady hand (or a tripod if you have one) you might even be able to capture the Man in the Moon.

Afocal imaging is a rather fancy name for quite a simple hack: point your phone into a pair of binoculars (or telescope) and take the picture that way. After that, you can crop out any rogue borders for an Insta-worthy Moon pic.

- Discover more essential tips and tricks in our lunar photography guide

Which constellation will the Moon be in?

On the night of full, the Super Blue Moon will be adjacent to the constellation Aquarius – where Saturn is currently residing until 2026 – before entering neighbouring Pisces on 2 September 2023.

The day before, on 30 August, the Moon will be 2.5 degrees south of Saturn in Aquarius, returning to roughly the same spot it was at the beginning of the month. A few days after full, on the 4 September, a now-waning gibbous Moon will have moved into Aries and will be 3.3 degrees north of Jupiter.

On 5 September, the Moon will be 2.8 degrees north of Uranus in Aries, before heading into Taurus on the 6th.

Will the Moon be blue?

Sadly, no. The Moon will not look blue in colour. We refer to a ‘Blue Moon’ in the metaphorical sense; something that is rare in occurrence, rather than a literal colour.

In fact, the Moon is more likely to look a yellow-orange colour when it’s near to horizon, before changing to a grey colour as it rises higher into the sky. But not blue, sorry!

The yellow colour is actually due to the interplay of the atmosphere with sunlight, and other particles (such as dust) in the atmosphere. When the Moon is low on the horizon, the light has a thicker layer of atmosphere to pass through, so the shorter wavelengths of light, like blue and green, are more effectively scattered than the longer wavelengths (red and yellow). This allows the yellow and red hues to dominate, leading to the Moon's yellowish colour.

But when the Moon is higher in the sky, the light has less of the atmosphere to pass through, resulting in less scattering and a clearer, whiter appearance.

Is the Blue Moon 2023 a supermoon?

Yes, like the first full Moon this month, the second full Moon in August 2023 is also a supermoon, and the third supermoon of the year!

Supermoons are an unofficial designation for when the Moon is 360,000km or closer to Earth in its orbit, and we'll often see two or three full supermoons in a row. In 2023, the July full Moon, the Buck Moon, the first full Moon in August the Sturgeon Moon, and this rare blue Moon, are also supermoons.

The Super Blue Moon this month will be a mere 357,344 km or 222,043 miles away from us, making it the biggest Moon of the year.

But you might want to make a special point of looking up for this one; the next Blue Moon that’s also a supermoon won’t be until 31 January 2037, at which time the Moon will be 358,080 km away.

When are the supermoons of 2023?

Here are the supermoons of 2023:

- 3 July 2023: Buck Moon

- 1 August 2023: Sturgeon Moon

- 31 August 2023: Blue Moon

- 29 September 2023: Harvest Moon

When is the next Blue Moon?

The next monthly Blue Moon will be 31 May 2026, and the next (albeit less exciting – sorry NASA) seasonal Blue Moon will be 19 August 2024.

Sometimes, we can get two Blue Moons in a single year. Thanks to the 28 days of February (29 in leap years), sandwiched either side by 31-day-months, we occasionally get two full Moons in January and March. This last happened in 2018, but we’ve got 14 years to wait until the next occurrence, in 2037.

What causes a supermoon?

As the Moon follows an elliptical (oval-shaped) orbit around the Earth, its distance from us changes over time. When the full Moon coincides with the perigee – the point in its orbit when it comes closest to the Earth – and providing the Moon is closer than 360,000 km to the Earth, we get a supermoon.

This is, of course, an unofficial designation, but one that has gained in popularity over recent years.

A supermoon appears around 7 per cent larger and around 15 per cent brighter than a standard full Moon, although this can be a little tricky to spot without having two Moons side-by-side.

Conversely, when a full Moon is at its furthest distance in its orbital path around the Earth (called the apogee), the Moon appears smaller. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this is termed a micromoon. If we compare a supermoon to a micromoon, a supermoon looks around 14 per cent bigger and 30 per cent brighter.

How often do we get a full Moon?

A full Moon occurs every 29 days, 12 hours, 44 minutes and 3 seconds, rounded to 29.53 days. This figure is calculated by the time it takes the Moon to make one full orbit around the Earth (one lunar cycle). It’s also known as one ‘synodic month’ after the Greek word synodic meaning ‘conjunction’, and is measured between two successive new Moons.

A full Moon occurs, when – as part of the lunar cycle – the Moon is fully illuminated by the Sun. For this to happen, the Moon and Sun need to be opposite each other in the sky, so a full Moon will always rise as the Sun sets. And yes, this means that a full Moon is one that’s technically in opposition, just like Saturn was a few days ago.

How will the Blue Moon affect me?

Unless you’re particularly susceptible to the placebo effect, then the Blue Moon is unlikely to have any effect on your life (unless you’re a werewolf, of course).

Some studies have suggested correlations between the full Moon and certain phenomena like changes in sleep patterns, emergency room visits, and psychological states. However, these correlations are often weak, and many studies have failed to consistently replicate these findings.

The majority of scientific literature indicates that any influence of the full Moon on human behaviour is likely to be negligible, instead attributed to other factors or biases. While the idea of the ‘lunar effect’ is popular in folklore and culture, the rigorous scientific evidence supporting significant effects on human behaviour remains limited.

About our expert, Pete Lawrence

Pete Lawrence is an experienced astronomer, astrophotographer, and presenter on BBC's The Sky at Night. Watch him on BBC Four or catch up on demand with BBC iPlayer.

Read more: