We have some sweet news for you, skygazers: the so-called Strawberry Moon, the sixth full Moon of 2021, is taking to the night sky tonight.

And it’s worth your attention for one simple reason. Occurring just days after the summer solstice – it will be the largest full Moon until next year, passing just 360,221km away from Earth.

Unfortunately, many parts of the UK may not be to see the Moon clearly due to cloud cover. However, to the naked eye, it will still appear full for two more nights.

So, why does the Strawberry Moon carry that unusual name? Will it carry a reddish hue all night, if at all? And how can you get an Insta-worthy photo of it? With the help of Dr Darren Baskill, physics and astronomy lecturer at the University of Sussex, we’ve answered these lunar quandaries and more below.

When is the Strawberry Moon?

The Strawberry Moon can be seen from the night ofThursday 24 June 2021in the UK (and around the rest of the Earth).

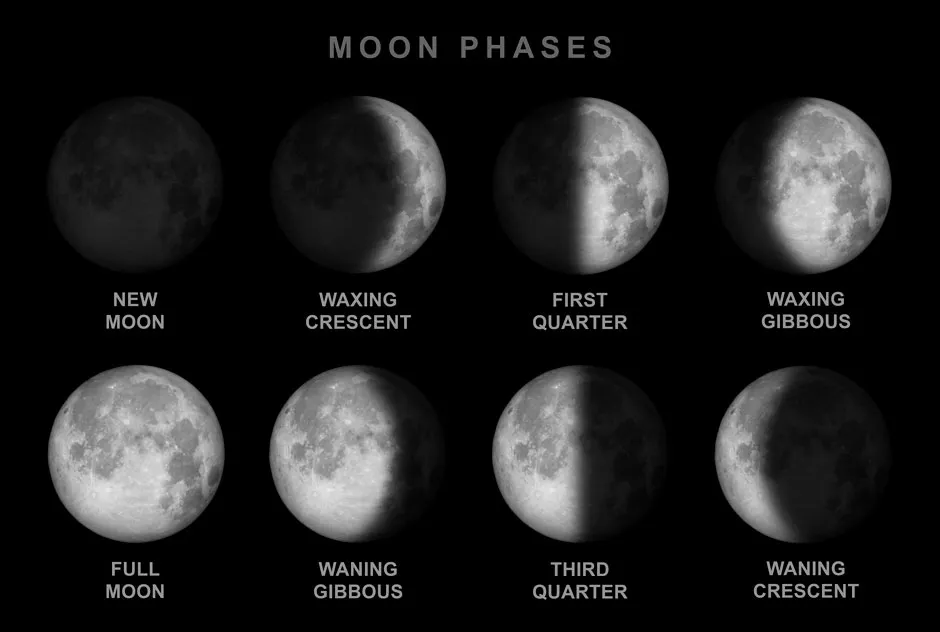

Astronomically speaking, the Moon is technically ‘full’ (reflecting the maximum amount of sunlight on Earth) for only a short period. This moment, called syzygy, occurs when Earth comes exactly between the Moon and the Sun.

This month, syzygy happens at 7:39pm in the UK on 24 June – an hour before the Moon rises. However, if you’re not looking at it with a telescope, the Moon will still appear ‘full’ two to three days after this moment, being above 99 per cent illuminated.

Interestingly, although the summer solstice was the longest day of the year, the UK's latest sunset will actually occur on Thursday 24 June 2021 (9:21pm in London).

Read more about the Moon:

Will the Strawberry Moon look red?

Despite its name, the Strawberry Moon won’t appear with a reddish hue all night. However, like any full Moon, it’s possible Earth’s neighbour could appear slightly crimson-coloured as it passes close to the horizon.

“The Moon will slightly change colour depending on where it appears in the sky,” explains Baskill.

“It’s all to do with the curvature of Earth. When you stand outside and look directly up, you’re looking through about 30km of atmosphere. But look to the horizon and you’re looking through about 300km of atmosphere.”

This means, when appearing from the horizon, the white light reflected by the Moon must travel further through the atmosphere. And, because blue (shorter wavelength) light ‘bends’ or ‘scatters’ more than so red light, not as much of it will reach your eye. Without those shorter wavelengths, only the more yellow/red colour will be left. Thus, the Moon may appear red in the sky.

“You can see evidence of this scattering effect yourself by shining a torch through a bottle of milky water,” says Baskill.

“The bottom sides of the bottle will appear blue (as that light most scatters), while the end of the bottle will appear red. This is because all the blue light has been bent away by this point.”

Why is it called a Strawberry Moon?

The name, according to some sources (such as the US Farmers’ Almanac), originates from native American groups, who harvested strawberries during this time of year. However many argue this explanation is oversimplistic at best, and culturally insensitive at worst.

This is because, as Baskill argues, such reasoning tends to condense all native American groups into one, ignoring how they are as culturally (and linguistically) diverse as Europeans.

“And no one seems to know who is inventing these generalisations!” Baskill says.

“Plus, native Americans have plenty of variations on Moon names – highlighting one is very much cherry-picking!”

Indeed, other native American groups also call the June full Moon the ‘Full Leaf Moon’, the ‘Green Corn Moon’ and ‘Peach Moon’.

How far away will the Strawberry Moon be?

When ‘full’, the Moon will be 360,221km away from Earth – almost nine times the circumference the globe. The Strawberry Moon will be over 8,000km closer to Earth than during July’s full Moon.

How often do full Moons happen?

Generally, once a month. A full Moon happens roughly every 29.5 days, the length of one lunar cycle.

Next’s month’s full Moon, known as the Buck Moon to some, will reach syzygy on Saturday 24 July.

What’s the best way of photographing the Strawberry Moon?

First thing you should know: it is possible to photograph the Moon with your phone alone. However, if you don’t want the lunar surface to look like an underwhelming white spec, there are some easy tips you can follow.

- Turn off your flash.

- Lower your camera’s ISO sensitivity.

- Raise its focus to 100 or more.

To make this easier, you can download one of the many astronomy photography apps.NightCap –available on theApp Store, £2.99 – is our top pick, making it onto our list ofbest astronomy apps. Android users can dowload ProCam X (HD Camera Pro), £4.99, from Google Play.

What about if you’re using a professional camera? Choose your lens wisely. “You need a reasonable zoom lens to capture a detailed picture,” explains Baskill.

To achieve a sharper image, he also recommends an aperture of f/9 to f/10 with a shutter speed of between 1/60th and 1/125th of a second. If your pictures are blurry, try leaning your camera against an object or – much better – use a tripod.

What details can I find when looking at the Moon?

The best time to study the Moon’s surface is actually not on the night of the full moon itself, as it can be too bright. Instead, pick a night a few days before or after the full moon to see the most detail.

The easiest features to spot with binoculars are the Moon’s craters – especially the younger ones, which tend to be brighter.

If you’re looking from the northern hemisphere, you’ll see a large, bright crater just to the left of the centre of the Moon’s surface. This is Copernicus, which is 93km-wide and thought to be around 800 million years old (relatively young by the Moon’s standards).

If you imagine a line of symmetry drawn vertically through the Moon’s disk, the Apollo 11 landing site, in the Sea of Tranquility, is pretty much where Copernicus would be reflected on the other side. Remember, if you’re looking from the southern hemisphere, the Moon will appear upside down compared to looking from the northern hemisphere.

You should also be able to see two more distinctive craters with your binoculars – Aristarchus, which is to the left of Copernicus, and the huge Tycho crater at the very bottom.

If you look closely enough you’ll see there are many more craters, each one evidence of the Moon’s billions of years of meteorite bombardment. – Abigail Beall

About our expert, Dr Darren Baskill

Dr Baskill is an outreach officer and lecturer in the department of physics and astronomy at the University of Sussex. A keen astrophotographer, he previously lectured at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, where he also initiated the annual Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition. Baskill is also a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society and a member of the Institute of Physics.

You can follow him on Twitter.

Read more: