The thought of spaceflight may make the heart skip a beat, but actually travelling beyond Earth could alter the organ’s cells.

With extended stays aboard the International Space Station (ISS) commonplace, and the likelihood of humans spending longer periods in space increasing, there is a need to better understand the effects of micro-gravity on cardiac function.

New research suggests heart muscle cells derived from stem cells have a remarkable ability to adapt to their environment during and after spaceflight.

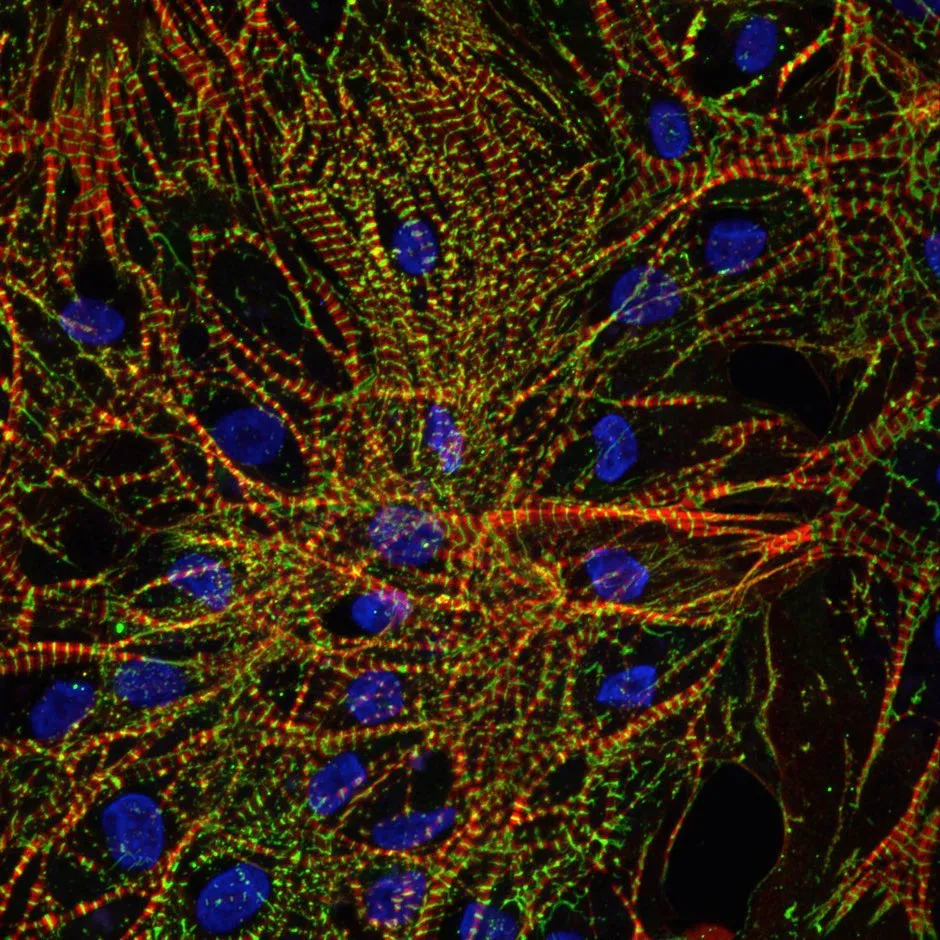

Scientists examined cell-level cardiac function and gene expression in human heart cells cultured aboard the International Space Station for five-and-a-half weeks.They found that exposure to micro-gravity changed the expression of thousands of genes, but largely normal patterns reappeared within 10 days after returning to Earth.

Read more about the body in space:

Senior study author, Joseph Wu, of Stanford University School of Medicine, said: “Our study is novel because it is the first to use human induced pluripotent stem cells to study the effects of spaceflight on human heart function.

“Micro-gravity is an environment that is not very well understood, in terms of its overall effect on the human body, and studies like this could help shed light on how the cells of the body behave in space, especially as the world embarks on more and longer space missions such as going to the Moon and Mars.”

Until now, most studies on how the heart reacts to micro-gravity have been conducted in either non-human models or at tissue, organ or systemic level.To address this, the beating cells were launched to the ISS aboard a SpaceX spacecraft as part of a commercial resupply service mission.Simultaneously, they were also cultured on Earth for comparison purposes.

When they returned to the planet, the cells showed normal structure and morphology.However, they did adapt by modifying their beating pattern and calcium recycling patterns.

Researchers sequenced the cells harvested at four-and-a-half weeks aboard the ISS, and 10 days after returning to Earth.Results showed that 2,635 genes were differentially expressed among flight, post-flight, and ground control samples.

Most notably, gene pathways related to mitochondrial function were expressed more in the space-flown cells, according to the research published in the Stem Cells Reports journal.

A comparison of the samples revealed the space cells adopted a unique gene expression pattern during spaceflight, which reverted to one that is similar to ground-side controls upon return to normal gravity.

Dr Wu added: “We’re surprised about how quickly human heart muscle cells are able to adapt to the environment in which they are placed, including micro-gravity.

“These studies may provide insight into cellular mechanisms that could benefit astronaut health during long-duration spaceflight, or potentially lay the foundation for new insights into improving heart health on Earth.”