Since its release in 1972, the table tennis-themed video game Pong has provided hours of entertainment to players from all genders, ages and walks of life. Now, thanks to an international team of neuroscientists, it can add a Petri dish layered with 800,000 living brain cells to that list.

Named DishBrain, the living model provides evidence that brain cells can display signs of intelligent behaviour, even when they are simply jumbled together in a dish.

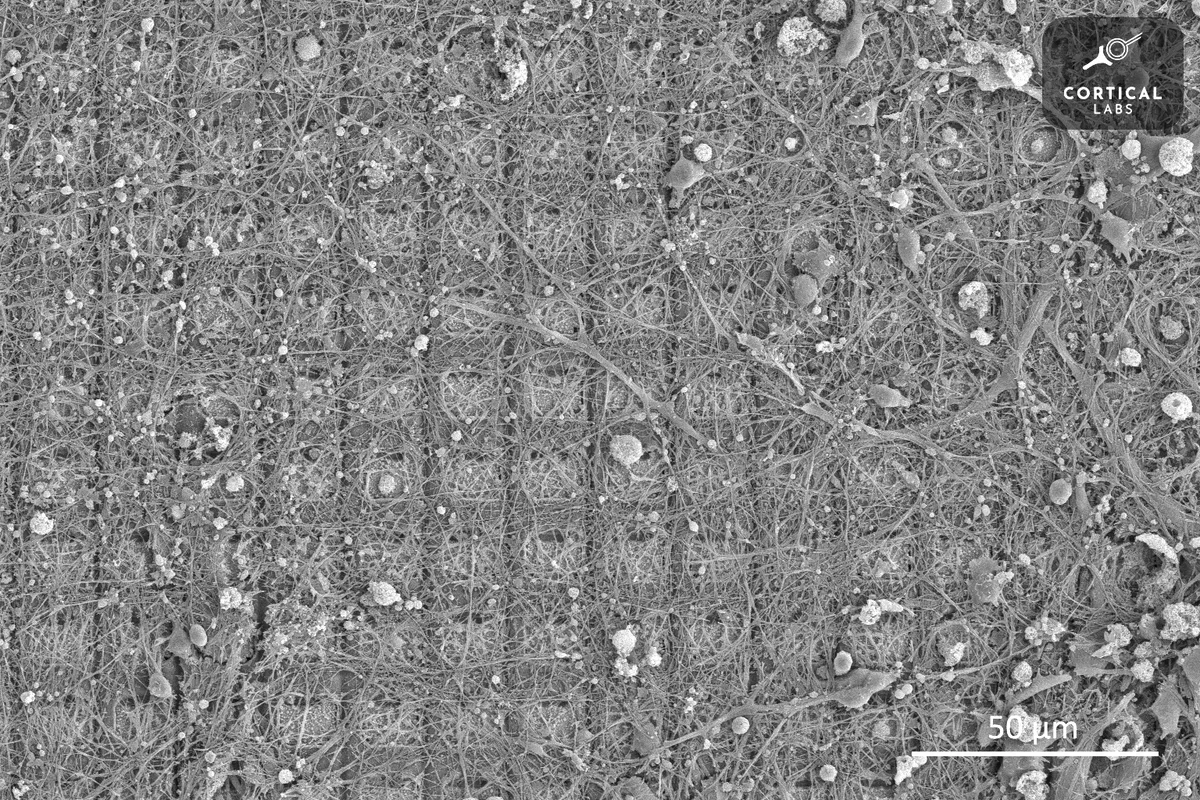

To create the model, the team harvested cells from embryonic mouse brains along with human brain cells derived from stem cells and grew them on top of a microelectrode array.

When playing a game of Pong, DishBrain was fed signals giving it information about the location of the ball. When the ball was on the left, electrodes on the left side of the array fired, and when the ball was on the right, electrodes on the right fired. Meanwhile, the distance of the ball from the paddle was indicated by the frequency of the signal.

The model was than given feedback via electric probes that got stronger the closer it was able to get to the ball. This in essence made the cells act as if they themselves were the paddle.

“The beautiful and pioneering aspect of this work rests on equipping the neurons with sensations — the feedback — and crucially the ability to act on their world,” said co-author Prof Karl Friston, a theoretical neuroscientist at University College London.

“This is remarkable because you cannot teach this kind of self-organisation; simply because — unlike a pet — these mini brains have no sense of reward and punishment.”

While previous experiments have successfully monitored the activity of neurons mounted onto electrode arrays, DishBrain is the first example of them being stimulated in a meaningful way, the researchers say.

The model could now potentially enable scientists to conduct experiments using real brain cells rather than computer models when researching the effect of neurodegenerative diseases and medicine on the brain.

“The translational potential of this work is truly exciting: it means we don’t have to worry about creating ‘digital twins’ to test therapeutic interventions,” said Friston.

“We now have, in principle, the ultimate biomimetic ‘sandbox’ in which to test the effects of drugs and genetic variants – a sandbox constituted by exactly the same computing (neuronal) elements found in your brain and mine.”

First, though, they want to see what effect alcohol will have on the model.

“We have shown we can interact with living biological neurons in such a way that compels them to modify their activity, leading to something that resembles intelligence,” said lead researcher Dr Brett Kagan, Chief Scientific Officer of biotech start-up Cortical Labs, in Melbourne Australia.

“We’re trying to create a dose response curve with ethanol – basically get them ‘drunk’ and see if they play the game more poorly, just as when people drink.”

Read more about neuroscience: