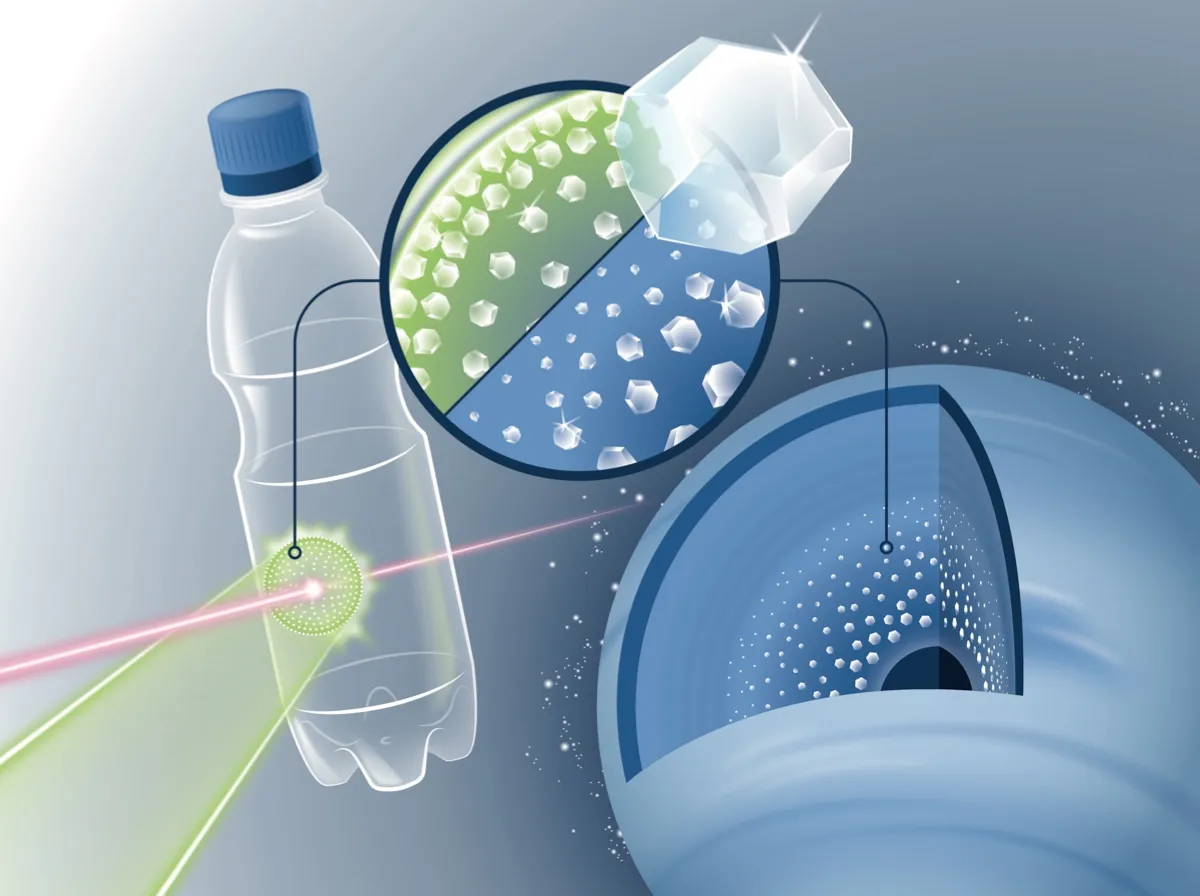

A team of German and French researchers have designed an intriguing experiment in order to find out more about the conditions in the ice giant planets, Neptune and Uranus. They fired extremely powerful laser flashes at a film of PET plastic – the same stuff used in plastic bottles – and found that the resulting shock wave produced tiny diamonds.

The scientists, from Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR), the University of Rostock and the École Polytechnique, wanted to simulate the extreme conditions found within the ice giants. Deep within these distant worlds, internal heat raises temperatures to thousands of degrees Celsius, and the atmospheric pressure is millions of times greater than on Earth.

When the team directed the powerful laser flashes at a sample of film, it generated a shock wave that compressed the material for a few nanoseconds to a million times the atmospheric pressure on Earth.

“We discovered that this extreme pressure produced tiny diamonds,” said Dominik Kraus, HZDR physicist and University of Rostock professor.

According to Kraus, the scientists opted for the everyday substance PET (polyethylene terephthalate) as it has a good balance between carbon, hydrogen and oxygen to simulate the interior of ice giant planets.

The experiment was conducted at California’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, using the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), a powerful, accelerator-based X-ray laser.

Two measurement methods were used to analyse what happened when the intensive laser flashes hit the film. These were X-ray diffraction, which determined whether nanodiamonds were produced, alongside a small-angle scattering (SAS) technique, to see how quickly and how large the nanodiamonds grew.

This research further supports the theory that on ice giants such as Neptune and Uranus, it could literally rain diamonds. Similar planets outside of our Solar System could also experience this sort of activity.

Read more about the ice giants:

The scientists believe that an unusual form of water known as 'superionic water' should be produced alongside the diamonds, and they want to carry out further research to confirm whether or not this is the case.

In addition to providing this exciting new knowledge about the ice giant planets, the research could also help establish a new way of producing nanodiamonds in industry, where they can be used, for example, in the production of quantum sensors. It could also help with the tailored production of nanometer-sized diamonds, which are currently used in the manufacture of abrasives and polishing agents.

“So far, diamonds of this kind have mainly been produced by detonating explosives,” said Kraus. “With the help of laser flashes, they could be manufactured more cleanly in the future. The X-ray laser means we have a lab tool that can precisely control the diamonds’ growth.”