Humans have a salamander-like ability to regrow cartilage in joints, new research suggests.

Cartilage in human joints can repair itself through a process similar to that used by animals such as salamanders and zebrafish to regenerate limbs, scientists have found.

The study identified a mechanism for repair that appears to be more robust in ankle joints and less so in hips.

Read more about the latest medical breakthroughs:

- Exoskeleton controlled by brain signals allows disabled man to walk

- New ultrasound diagnosis technique 'may be able to pick up cancers far earlier'

- Low-cost arthritis drug 'significantly reduces' symptoms of blood cancers

Researchers say the finding could potentially lead to treatments for osteoarthritis, the most common joint disorder in the world.

Professor Virginia Kraus from the departments of Medicine, Pathology and Orthopaedic Surgery at Duke University Medical Centre in America was the senior author.

She said: “We believe that an understanding of this salamander-like regenerative capacity in humans, and the critically missing components of this regulatory circuit, could provide the foundation for new approaches to repair joint tissues and possibly whole human limbs.”

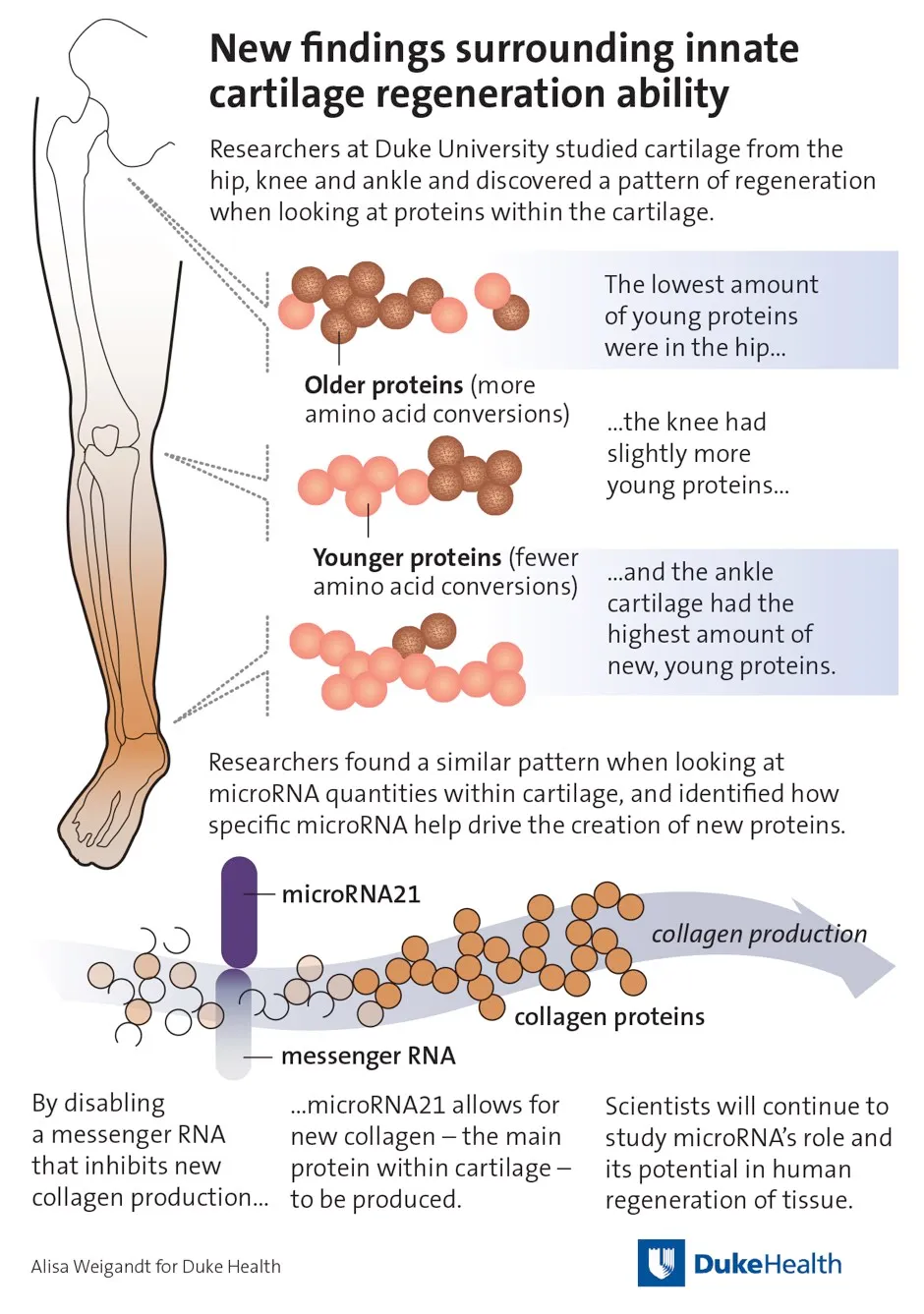

The scientists devised a way to determine the age of proteins using internal molecular clocks integral to amino acids, which convert one form to another.

Newly-created proteins in tissue have few or no amino acid conversions, while older proteins have many.

Understanding this process enabled researchers to identify when key proteins in human cartilage, were young, middle-aged or old.

According to the research published in Science Advances, the age of cartilage largely depended on where it was in the body.

Cartilage in ankles is young, is middle-aged in the knee and old in the hips.

This correlation between the age of human cartilage and its location in the body aligns with how limb repair occurs in certain animals.

The scientists say their discovery also suggests why hip and knee injuries take longer to heal, and often develop into arthritis.

The researchers also found that molecules called microRNA regulate this process, and are more active in animals that are known for limb, fin or tail repair, including salamanders, zebrafish, African fresh water fish and lizards.

They believe microRNAs could be developed as medicines that might prevent, slow or reverse arthritis.

Lead author Dr Ming-Feng Hsueh, said: “We were excited to learn that the regulators of regeneration in the salamander limb appear to also be the controllers of joint tissue repair in the human limb.”

Reader Q&A: Why can’t bones grow back?

Asked by: Simon Brown, Glasgow

Bones do repair themselves to some extent. But they can’t regenerate or replace themselves fully for the same reason that we can’t grow ourselves a new lung or an extra eye.

Although the DNA to build a complete copy of the entire body is present in every cell with a nucleus, not all of that DNA is active. Most of our cells become specialised during embryonic development so that they only divide to produce cells appropriate to their location in the body.

This is an essential mechanism that keeps us all looking roughly the right shape, despite the fact that our cells are continually dividing and dying off. There seems to be an inverse relationship between how complex an organism is and how well it is able to regenerate after an injury. So newts can regrow a leg but humans can’t.

Read more:

Prof Kraus said: “We believe we could boost these regulators to fully regenerate degenerated cartilage of an arthritic joint.

“If we can figure out what regulators we are missing compared with salamanders, we might even be able to add the missing components back and develop a way someday to regenerate part or all of an injured human limb.

“We believe this is a fundamental mechanism of repair that could be applied to many tissues, not just cartilage.”