A fish-shaped robot that can collect tiny pieces of plastic waste has been developed by scientists at Sichuan University, China. The bot uses light from a laser to flap its tail side-to-side and has a body that can attract molecules found on microplastics, causing them to stick to it as it swims past.

The robo-fish was, in part, inspired by marine life – its moving body uses a structure similar to a naturally strong and flexible substance found on the inside surface of clam shells: mother-of-pearl.

Mother-of-pearl, also known as nacre, is a layered material that looks almost like a brick wall under the microscope. It's this structure that the team mimicked in their robot, as the sliding layers enabled it to move its tail but the strength of the overall design made it more durable.

Now that the team have proven the robo-fish concept works, they'll move onto developing its ability to dive deeper and carry more microplastics out of the ocean.

All items that contain plastic can release microscopic amounts of plastic debris, which are called microplastics.These small bits of material – less than 5mm in size – build up on the seafloor. There, they can be mistaken for food and get stuck in an animal’s digestive tract, leading to starvation. Some plastics have been treated before use, and as their coating degrades it can release toxic chemicals into the water that poison nearby marine life.

No-one knows exactly how much plastic is in the world’s oceans. The most recent figures, published in 2015, estimate that somewhere between 4.8 and 12.7 million tonnes of plastic enter the seas each year.

While reducing plastic waste and filtering wastewater before it gets to the ocean can help minimise the amount of microplastics in our seas, cleaning the already-tainted water is difficult. The tiny particles can get lodged deep within cracks and crevices on the seafloor, areas that are hard to reach using large and inflexible robots.

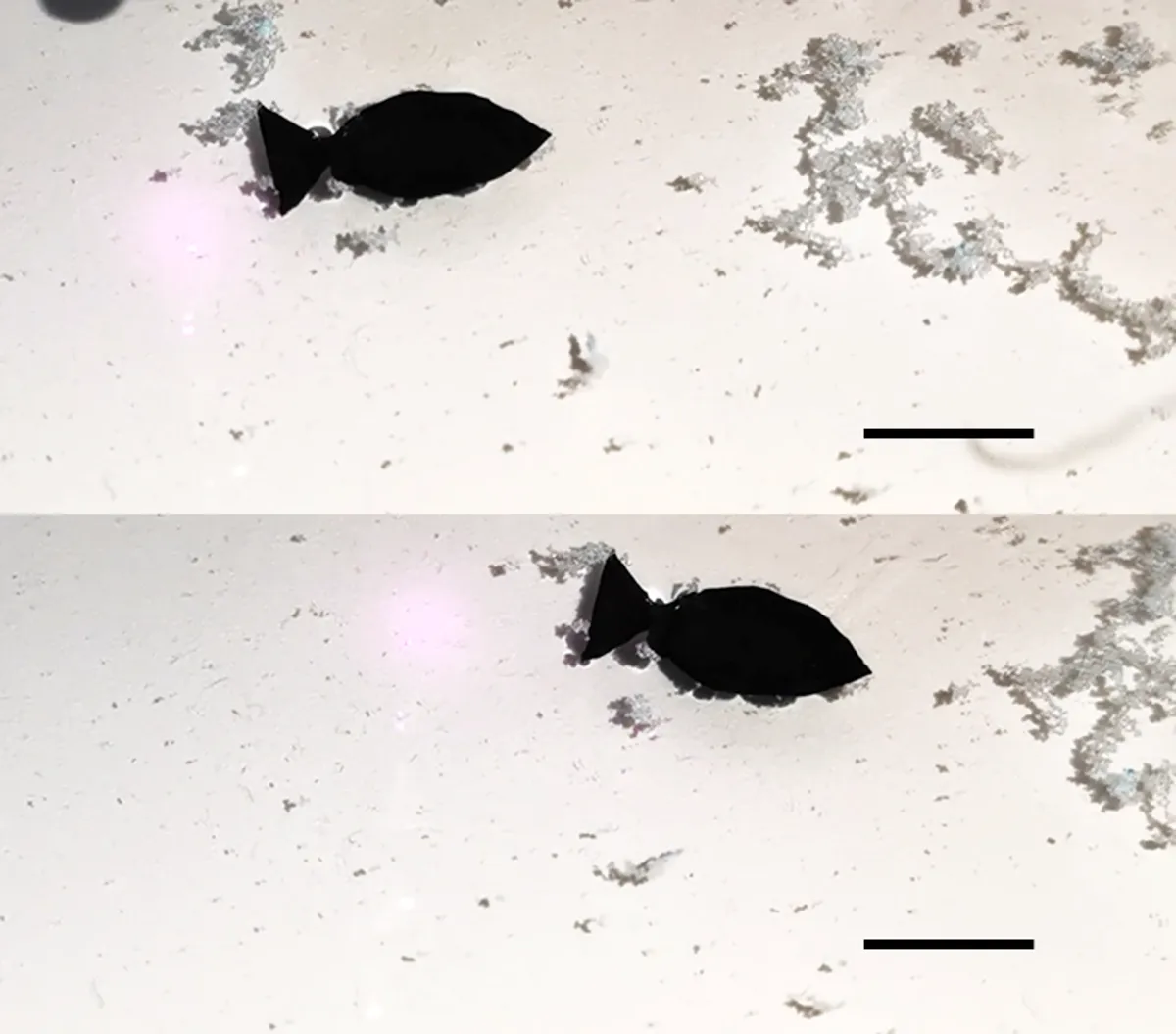

The new robo-fish, however, is just 15mm long. Its clever design also allows it to swim in all directions using a light source as its power. When a laser is shone on the fish's tail, the light deforms the material, causing it to bend. Done several times in succession makes the tail flap side to side, and the robo-fish can swim up to 2.67 times its own body length per second.

Its body also contains molecules that are slightly negatively charged, which attract the parts of the microplastics that are positively charged. This means the robo-fish is so 'sticky', it doesn't need to get so close as to touch every single microplastic to collect it.

Currently, though, the team have only tested the fish on microplastics that float in water. The next test will be to see if the robot can attract plastic in as challenging an area as the seafloor.

Read more about microplastics: