A new species of prehistoric scorpion may have been capable of leaving its marine habitat and venturing onto land, new research suggests.

The findings indicate that Parioscorpio venator is the oldest-known scorpion reported to date, coming from the early Siluarian period – around 437.5 to 436.5 million years ago.

Scorpions are among the first animals to have moved from the sea onto land, but because their fossil record is limited, how and when they adapted to dry life remains unclear.

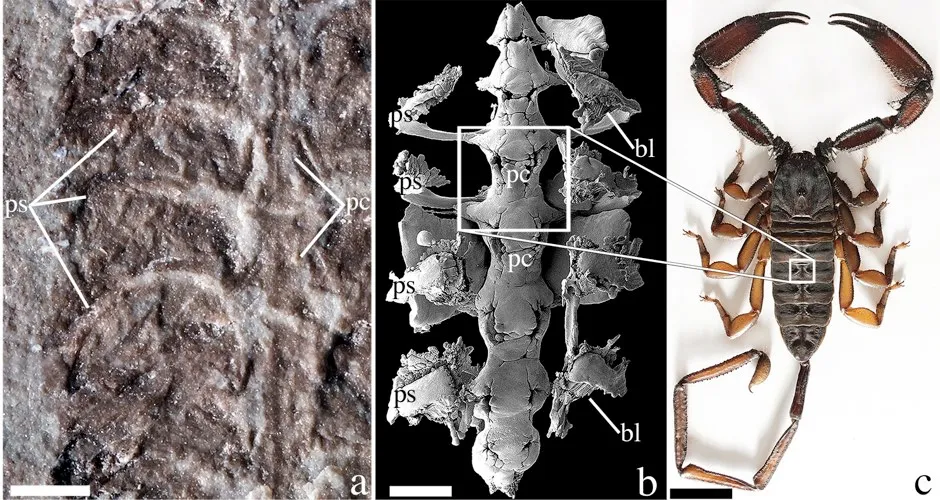

Andrew Wendruff, a palaeontologist at Otterbein University in the US, and colleagues describe two well-preserved specimens of a previously-unknown fossil scorpion species.

They were discovered in the Waukesha Biota in Wisconsin, US, and are older than Dolichophonus loudonensis, from Scotland, which was previously accepted as the oldest known scorpion species.

Read more about prehistoric creatures:

- Ancient 8-metre crocodile needed extra bones to move around

- Ancient rhino tooth provides world's oldest sample of genetic data

- Oldest-ever liquid blood found in 42,000-year-old ice age horse

P. venator shows some primitive characteristics present in other early marine organisms, including compound eyes, as well as characteristics found in present-day scorpions, such as a tail terminating in a stinger.

Both of the newly discovered specimens show details of internal anatomy, including narrow, hourglass-shaped structures that extend along much of the middle part of the body.

These structures are very similar to the circulatory and respiratory systems in present-day scorpions, as well as those of modern horseshoe crabs, the authors say.

The study, published in the Scientific Reports journal, sets out that no lungs or gills are evident in fossils.

However, it adds that their similarity to horseshoe crabs, which can breathe on land, suggests that while the oldest scorpions may not have been fully terrestrial, they may have forayed onto land for extended periods of time.

The authors write: “Anatomical details preserved in P. venator suggest that the physiological changes necessary to accommodate a marine-to-terrestrial transition in arachnids occurred early in their evolutionary history.

“Whether P. venator was a fully terrestrial arthropod is uncertain.

“The close similarity of its preserved pulmonary-cardiovascular structures with those of extant scorpions and horseshoe crabs hint at the possibility of extended stays on land.”

The thought experiment: How could I become a fossil?

- Pick the right place to dieFossils form best in oxygen-starved environments that keep out bacteria. These conditions also encourage the chemical reactions that replace your body’s soft tissues with hard minerals. Drowning in a stagnant lake is a good bet, or a cold sea.

- Get buried quicklyA layer of sediment keeps out scavengers and protects your skeleton from being scattered by currents. Shallow seas are good because a constant, gentle rain of dead plankton and sediment is washed down by rivers. It will take at least 10,000 years to fossilise you.

- Get discoveredIf you want to be found as a fossil, pick a place where the motion of tectonic plates will lift you above sea level, so erosion can start peeling away the layers of rock above you. If the rock below you is crumbly, so much the better – it will collapse into cliffs that expose fossils faster.

Read more thought experiments: