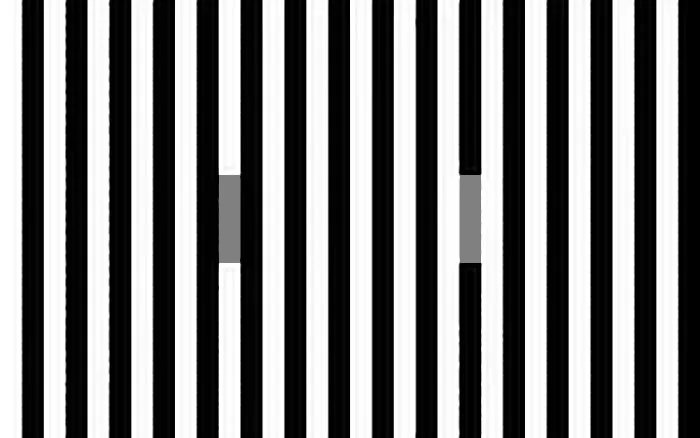

See the image above? It’s playing tricks on your eyes: despite initial appearances, the bar in the middle of the picture is actually a singular shade of grey – it only appears lighter at one end due to the background gradient.

Such 'simultaneous contrast' illusions like this have long fascinated scientists, with many pondering why these pictures so easily trip us up. However, a new breakthrough study from the University of Exeter may now have unravelled the mystery: high-contrast optical illusions are caused by limitations in our eyes, rather than more complex neurological processes involving context and prior knowledge.

In simpler terms, it's not your brain's processing power that's to blame, but rather the hardware of your visual system.

“This throws into the air a lot of long-held assumptions about how visual illusions work,” Dr Jolyon Troscianko – one author of the study, published in PLOS Computational Biology – said.

As previously discovered, our eyes communicate with the brain by adjusting how fast their neurons fire. However, as Troscianko explained, “There is a limit to how quickly these neurons can fire, and previous research failed to consider how this limitation might impact our perception of colour."

In the study, researchers created a computer model that mimicked the ‘limited bandwidth’ of the human eye, replicating the way we perceive visual information. When this model was exposed to 'simultaneous contrast' illusions, the researchers observed that the model would become overwhelmed by the presence of high contrasts, resulting in a distorted perception of the image.

“Our model shows how neurons with such limited contrast bandwidth can combine their signals to allow us to see these enormous contrasts, but the information is ‘compressed’ – resulting in visual illusions,” said Troscianko.

The model, the researchers say, shows how different neurons have evolved to become finely tuned at processing subtle variations across a range of colours. “For example, some neurons are sensitive to very tiny differences in grey levels at medium-sized [ranges], but are easily overwhelmed by high contrasts,” said Troscianko.

“Meanwhile, neurons coding for contrasts at larger or smaller scales are much less sensitive, but can work over a much wider range of contrasts, giving deep black-and-white differences.”

In future, scientists hope to use the computer model to explore the colour perception of animals with different vision neuron bandwidths to humans.

Read more: