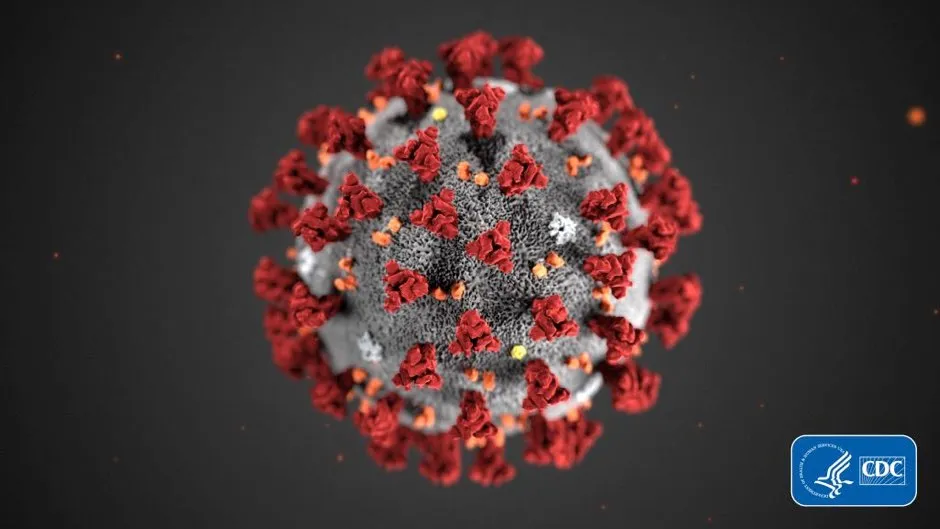

The virus that causes COVID-19 has not mutated into different types, according to new analysis.

Recent research had suggested more than one type of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is now circulating, with one strain being more aggressive and causing more serious illness than the other.

However using analysis of SARS-CoV-2 virus samples, scientists from the Medical Research Council-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research (CVR) have found only one type of the virus.

Viruses, including the one causing COVID-19, naturally accumulate mutations – or changes – in their genetic sequence as they spread through populations.

Scientists said most of these changes will have no effect on the biology of the coronavirus or the aggressiveness of the disease they cause.

Read the latest coronavirus news:

- Testing faults blamed for South Korea coronavirus reinfection results

- 'Not enough evidence' to support post-infection immunity passports, warns the WHO

- Coronavirus: 6,000 patients volunteer blood plasma for trial

Dr Oscar MacLean, from the CVR, said: “By analysing the extensive genetic sequence variation present in the genomes of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the evolutionary analysis shows why these claims that multiple types of the virus are currently circulating are unfounded.

“It is important people are not concerned about virus mutations – these are normal and expected as a virus passes through a population.

“However, these mutations can be useful as they allow us to track transmission history and understand the historic pattern of global spread.”

It was reported earlier this year that scientists had found two or three strains of SARS-CoV-2 circulating in the population, evidenced by certain mutations that had been detected.

However extensive analysis by the team found these detected mutations are unlikely to have any functional significance, and, importantly, do not represent different virus types.

The centre’s CoV-GLUE resource tracks SARS-CoV-2’s amino acid replacements, insertions and deletions, which have been observed in samples from the pandemic.

To date, the database has catalogued 7,237 mutations in the pandemic.

Scientists said that while this may sound like a lot of change, it is a relatively low rate of evolution for a virus that has ribonucleic acid (RNA) as its genetic material.

They expect more mutations will continue to accumulate as the pandemic continues.

Most observed mutations would be expected to have no, or minimal, consequence to the virus’s biology, however tracking these changes can help scientists better understand the pandemic and how COVID-19 is spreading in the community.

The study is published in Virus Evolution and the work was funded by the Medical Research Council.

Reader Q&A: Why don’t viruses like the flu die off when no one is ill?

Asked by: Andrew Cirel, via email

Strictly speaking, viruses can’t ‘die off’ as they’re just inanimate strips of genetic material plus other molecules. But the reason that they keep coming back is because they’re always infecting someone somewhere; it’s just that at certain times of the year, they’re less able to infect enough people to trigger a full-blown epidemic.

Many viruses flare up during the winter because people spend more time indoors in poorly-ventilated spaces, breathing in virus-laden air and touching contaminated surfaces. The shorter days also lead to lower levels of vitamin D, and this weakens our disease-fighting immune system. Experiments also suggest that the flu virus in particular remains infectious for longer in low temperatures.

But even when conditions aren’t ideal, viruses will find enough people to infect to ensure their survival, until they can come roaring back in an epidemic.

Read more: