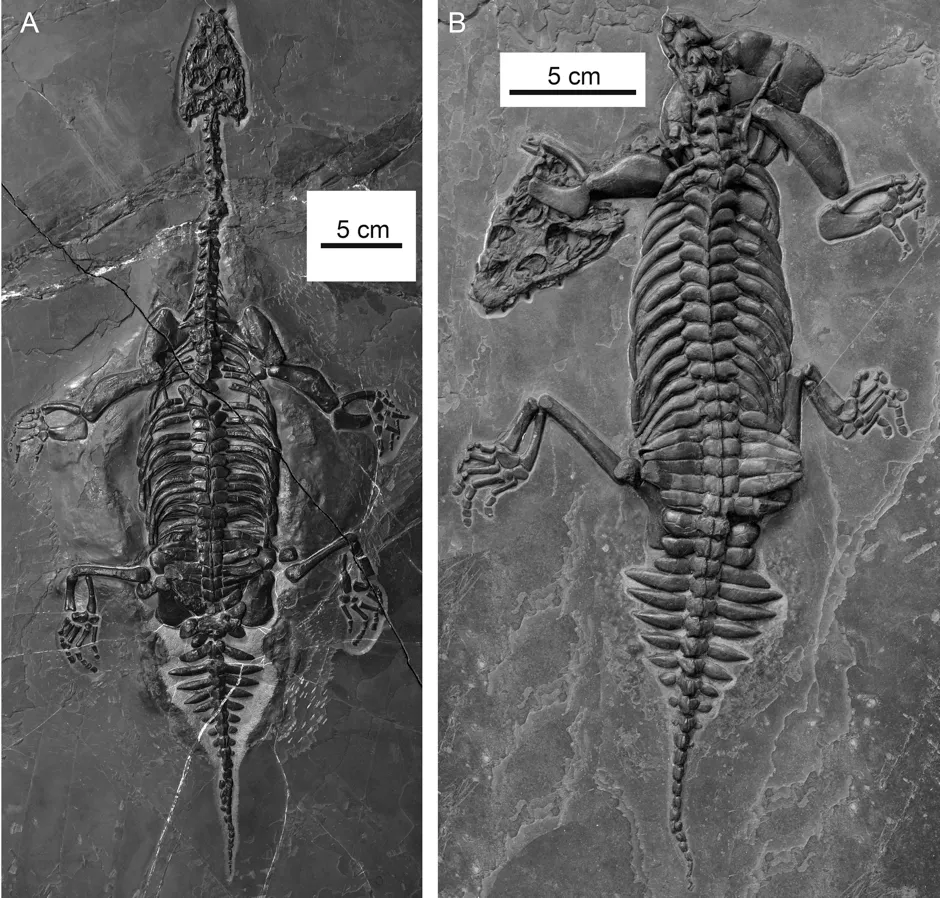

Analysis of two skeletons has revealed a new species of nothosaurs – reptiles that lived in the water during the Triassic period.

The 60cm long skeletons were identified as nothosaurs due to their small heads, wide snout, long neck and flipper-like limbs, but researchers noted in their paper that the two specimens "differed from other known nothosauroids mainly in having an unusually short tail".

"A long tail can be used to flick through the water, generating thrust, but the new species we've identified was probably better suited to hanging out near the bottom in shallow sea," said Dr Qing-Hua Shang from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and co-author of the study.

Read more about ancient reptiles:

- Ancient teeth reveal how the first mammals lived more like reptiles

- Mystery solved: 240-million-year-old reptile with 'extraordinarily long neck' lived in the ocean

- Ancient reptile ‘well-preserved’ in stomach of slightly larger reptile

The reptile was able to use its short, flattened tail for balance, "like an underwater float", which meant it used very little energy to move through the water while looking for its prey.

Other adaptations included strong forelimbs, short front feet and thick, dense bones, which the researchers say increased Brevicaudosaurus jiyangshanensis'sstability while underwater, though it limited its ability to swim at speed.

It was B. jiyangshanensis'sthick bones that made it neutrally buoyant. While in shallow water, the reptile's density was the same as the density of the water, meaning it didn't sink or rise – it could float almost effortlessly. The size of the skeleton's ribs also suggest the reptile had large lungs, increasing the amount of time it could spend underwater searching for food.

When looking at the head of the new species, the researchers were interested in a bone found in the middle ear, called the stapes. If found, the bone was expected to be thin as with other marine reptiles of its time, however the new species stapes was "relatively massive compared with that of some aquatic reptiles". As this bone is used for sound transmission, the scientists say B. jiyangshanensis'sthick, bar-shaped bone suggested it had good hearing.

"Perhaps this small, slow-swimming marine reptile had to be vigilante for large predators as it floated in the shallows, as well as being a predator itself," said co-author Dr Xiao-Chun Wu from the Canadian Museum of Nature.

Reader Q&A: How do dinosaur footprints get fossilised?

Asked by:Rob French, Sheffield

First, the creatures must step through sediment that is pliable enough to record their footprints, but not so pliable it gets washed away before being protected by fresh sediment.

Each footprint then has three chances to become a fossil: as the original impression (the ‘true track’), as its fainter impression in the underlying layers (the ‘undertrack’), or by new sediment filling in the original impression (the ‘natural cast’) and hardening. Either way, as the layers of sediment build up, the pressure turns them to rock which – given yet more luck – will preserve the print intact for aeons.

Read more: