Neuroscientists are poised to gain new insights into how our minds work, thanks to a breakthrough in non-invasive 3D brain scanning.

Testing the new technique – which is called diffuse optical localisation imaging (DOLI) – researchers from the University of Zurich injected a live mouse with special fluorescent microdroplets that became distributed throughout the bloodstream.

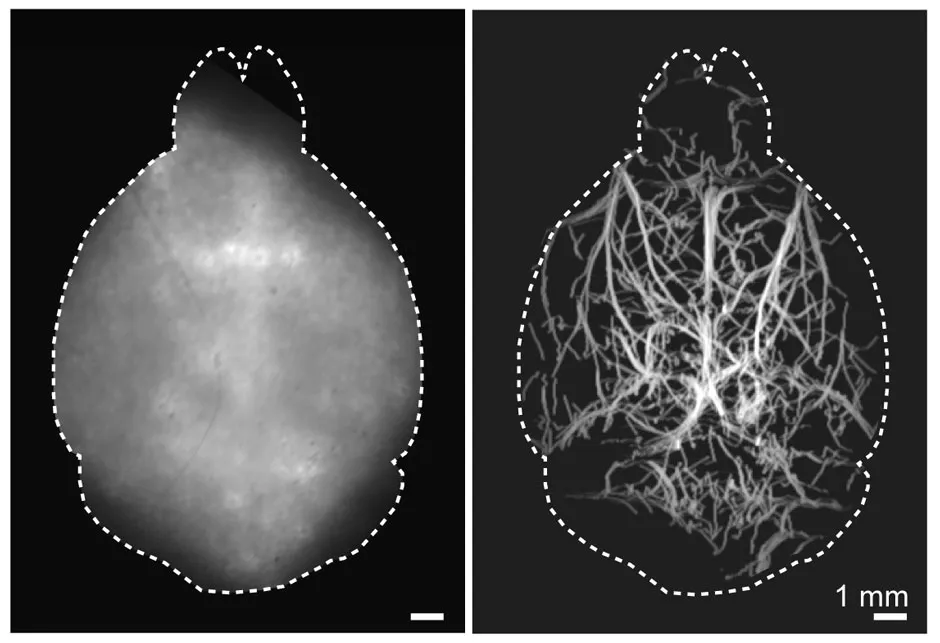

Highly efficient short-wave cameras (which take advantage of a near-infrared spectral window) tracked the fluorescent to draw a map of the deep cerebral network within the mouse's brain.

Previous microscopy techniques generated unclear images due to intense light scattering. However, the DOLI technique can create a clear picture of the brain at the capillary level by using a fluorescent filled with tiny lead-sulfide-based particles called quantum dots.

Additionally, unlike past procedures, DOLI does not need to break the animal’s skull and scalp to work.

It is hoped the new non-invasive technique will lead to a better understanding of how brains work, including how neurological diseases first form.

"Enabling high-resolution optical observations in deep living tissues represents a long-standing goal in the biomedical imaging field," said research team leader Prof Daniel Razansky, who published the group’s findings in Optica, The Optical Society's journal.

"DOLI's superb resolution for deep-tissue optical observations can provide functional insights into the brain, making it a promising platform for studying neural activity, microcirculation, neurovascular coupling and neurodegeneration."

Before being tested on live mice, the new scanning method was trialled on ‘tissue phantoms’, synthetic models that mimic brain tissues.

It remains to be seen if the results will be replicated on humans. However, researchers already hope to create even clearer pictures of the brain using by developing new fluorescents that are stronger, smaller and more stable.

"We expect that DOLI will emerge as a powerful approach for fluorescence imaging of living organisms at previously inaccessible depth and resolution regimes," said Razansky.

Read more news about the brain: