SpaceX is set to send four astronauts into low-Earth orbit as part of its first operational crewed flight to the International Space Station (ISS).

The crew, consisting of one Japanese and three US astronauts, is scheduled for lift-off shortly after midnight on Sunday, on a rocket and capsule system built by billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk’s aerospace company.

For NASA, it marks the beginning of using private firms as a 'taxi service' to fly its crew to and from the space station.

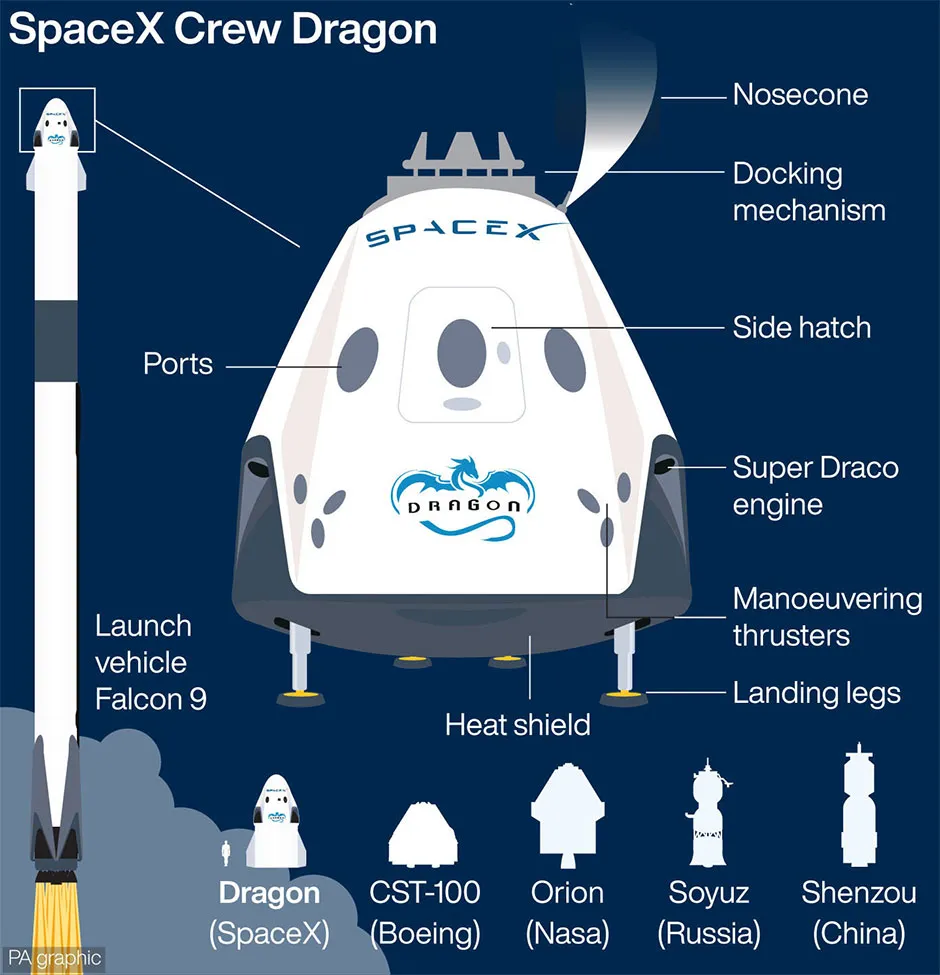

The US space agency announced this week that it had certified SpaceX’s Crew Dragon capsule and Falcon 9 rocket to carry astronauts, making it the first commercial human spaceflight system in history.

Read more about space travel:

- How will private space travel change the way we explore the Solar System?

- Everything you need to know about space travel (almost)

“This is a great honour that inspires confidence in our endeavour to return to the Moon, travel to Mars, and ultimately help humanity become multi-planetary," SpaceX chief executive Elon Musk said in a statement.

Since ending its Space Shuttle programme in 2011, NASA has depended on Russia’s space agency Roscosmos to transport its astronauts to the space station, at a cost of around 90 million US dollars (£67m) per seat.

In 2014, it awarded SpaceX and Boeing contracts to provide crewed launch services to the space station as part of its Commercial Crew Program.The SpaceX certification ends NASA's reliance on Russia and comes with a price of about 55 million US dollars (£40m) per astronaut.

“NASA's partnership with American private industry is changing the arc of human spaceflight history by opening access to low-Earth orbit and the International Space Station to more people, more science and more commercial opportunities," Phil McAlister, director of commercial spaceflight development at NASA, said in a statement.“We are truly in the beginning of a new era of human spaceflight.”

Back in May, Elon Musk’s company made history when it became the first private company to send humans into orbit.US astronauts Robert Behnken and Douglas Hurley travelled to the space station and back as part of a mission to demonstrate SpaceX’s capability to safely perform crewed missions.

The current mission, named Crew 1, will see the Crew Dragon capsule carry NASA's Mike Hopkins, Victor Glover, and Shannon Walker, as well as Japan’s Soichi Noguchi, to the space station.

The astronauts will spend six months on the orbiting space laboratory, conducting scientific experiments and performing various other tasks.

The crew is set to blast off from the Launch Complex 39A at the Kennedy Space Centre in Florida at 00:49 UK time on 15 November, in a journey that is expected to last around nine hours.

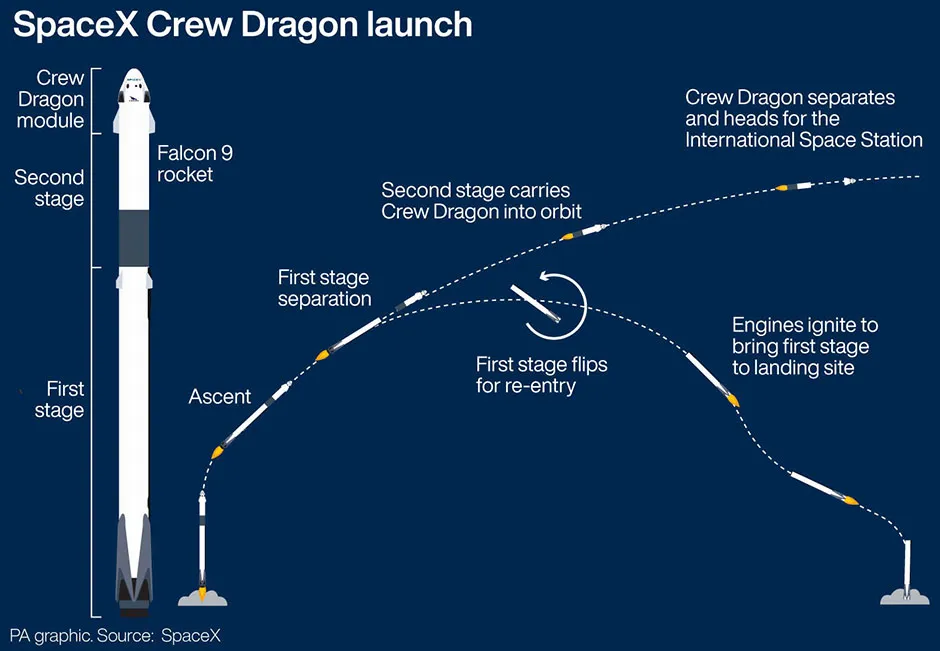

Shortly after lift-off, the Falcon 9 rocket will separate into a first stage and a second stage.The first stage will return to a SpaceX landing ship stationed off the coast of Florida, while the second part of the rocket continues the journey with the Crew Dragon.

Once in orbit, the Crew Dragon will separate from the second stage and travel at around 27,000km/h (17,000mph).The craft is expected to rendezvous and dock with the space station on Sunday at 9:20am UK time.

The astronauts will join three other space station residents – NASA's Kate Rubins and Russia’s Sergey Ryzhikov and Sergey Kud-Sverchkov – to become part of the Expedition 64 crew.

Meanwhile, NASA's other taxi service for hire, Boeing, is not expected to fly its first crew until the summer of 2021.

Reader Q&A: Why is a rocket trajectory curved after launch?

Asked by: Fred Wilhelm, US

Students have long been taught that all projectiles follow a curved path known as a parabola. The explanation is that as they fly, they cover distance both horizontally and vertically – but only the latter is affected by the force of gravity, which bends the path of the projectile into a parabola.

For long-range rockets, things are more complex. For example, air resistance must be taken into account. But even ignoring that, a projectile doesn’t really follow a parabola – because the Earth isn’t flat. This means that gravity doesn’t simply pull objects straight back down. Instead, it pulls them towards the centre of the Earth, whose direction changes as the projectile moves further down-range, away from the launch site. Detailed calculations then reveal that the true trajectory is not a parabola, but part of an ellipse.

Read more: