An ancient reptile which stands out because of its long, giraffe-like neck may have lived in the ocean, and not on land, scientists have said.

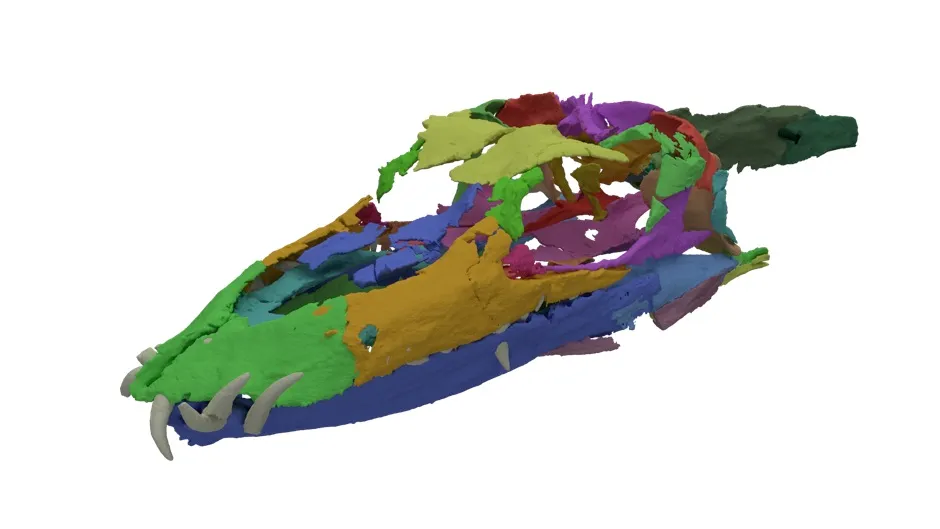

The findings, published in the journal Current Biology, are based on a digital reconstruction of the crushed skull of Tanystropheus, which lived more than 240 million years ago.

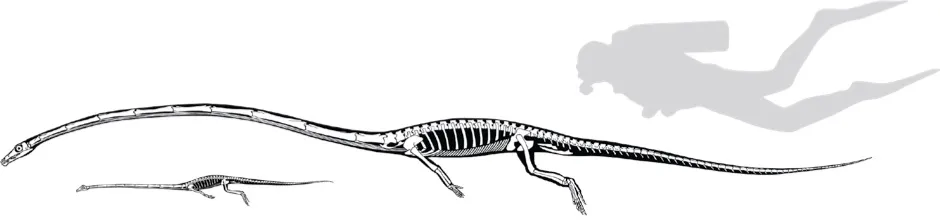

Although first described in 1852, scientists have been debating whether the reptile, which is over 6m long, lived on land or under water because its “bizarre body didn’t make things clear one way or the other”.

Read more fossil discoveries:

- 200 million-year-old fossil shows dinosaur 'walked like a guineafowl'

- Ichthyosaur's pebble-like teeth used to 'crush the shells of their prey'

- Fossil footprints 'provide a tantalising snapshot of humankind’s earliest days'

Tanystropheus’s neck was 3m long – three times as long as its torso – but not very flexible and had only 13 extremely elongated vertebrae to hold it in place.

The researchers said the reptile’s neck bears similarities to the tall neck of a giraffe, which has only seven neck bones.However, skull reconstruction revealed Tanystropheus to have “several very clear adaptations for life in water”.

The researchers found its nostrils to be located on top of the snout, similar to that of modern-day crocodiles.

In addition, the teeth were long and curved, which would have helped in catching slippery prey such as fish.

Olivier Rieppel, a paleontologist at the Field Museum in Chicago, US, and one of the authors on the study, described the creature as “a stubby crocodile with a very, very long neck”.

He added: “That neck doesn’t make sense in a terrestrial environment.

“It’s just an awkward structure to carry around.”

In spite of being a creature of the ocean, the researchers believe Tanystropheus may have been a poor swimmer, because of “the lack of visible adaptations for swimming in the limbs and tail”.

We expected the bizarre neck of Tanystropheus to be specialised for a single task, like the neck of a giraffe. But actually, it allowed for several lifestyles. This completely changes the way we look at this animal

Stephan Spiekman, University of Zurich

Stephan Spiekman, a paleontologist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland and lead author on the study, said: “It likely hunted by stealthily approaching its prey in murky water using its small head and very long neck to remain hidden.”

Tanystropheus lived 242 million years ago, during the middle Triassic period, when dinosaurs were just starting to emerge on land and giant reptiles dominated in the sea.

Remains of this creature were unearthed at Monte San Giorgio on the border between Switzerland and Italy.

Scientists have also found fossils in the area that look similar to Tanystropheus but are just 1.2m long.

To find out whether these smaller specimens were juveniles or a separate species, the researchers examined the bones to look for growth rings, which then determine the age of the species.

Analysis revealed the smaller creatures to be mature, indicating they belonged to a different species, Tanystropheus longobardicus.

Nick Fraser, keeper of natural sciences at National Museums Scotland and a co-author on the paper, said: “It is hugely significant to discover that there were two quite separate species of this bizarrely long-necked reptile who swam and lived alongside each other in the coastal waters of the great sea of Tethys approximately 240 million years ago.”

Mr Spiekman added: “These two closely related species had evolved to use different food sources in the same environment.

“The small species likely fed on small shelled animals, like shrimp, in contrast to the fish and squid the large species ate.

“This is really remarkable, because we expected the bizarre neck of Tanystropheus to be specialised for a single task, like the neck of a giraffe.

“But actually, it allowed for several lifestyles. This completely changes the way we look at this animal.”

Reader Q&A: How do dinosaur footprints get fossilised?

Asked by:Rob French, Sheffield

First, the creatures must step through sediment that is pliable enough to record their footprints, but not so pliable it gets washed away before being protected by fresh sediment.

Each footprint then has three chances to become a fossil: as the original impression (the ‘true track’), as its fainter impression in the underlying layers (the ‘undertrack’), or by new sediment filling in the original impression (the ‘natural cast’) and hardening. Either way, as the layers of sediment build up, the pressure turns them to rock which – given yet more luck – will preserve the print intact for aeons.

Read more: