Rock and soil samples taken from Mars in the search for life on the Red Planet are to be selected by UK researchers.

Scientists at Imperial College London and the Natural History Museum will help the NASA Perseverance rover select the Martian samples to be brought back to Earth, as it searches for evidence of ancient microbial life.

The mission to Mars is set to launch on Thursday.

Jezero crater, the 28-mile (45km) wide destination of Perseverance, contains sediments of an ancient river delta, a location where evidence of past life could be preserved if it ever existed on the planet.

Read the latest Mars news:

- Tianwen-1: China Mars mission launches aboard Long March-5 rocket

- ExoMars mission delayed until 2022

- Marsquakes caused by tectonic activity, NASA’s InSight probe confirms

Professor Sanjeev Gupta, from Imperial, will help NASA oversee mission operations from a science and engineering point of view.

He said: “This is crucial to understand what the Martian climate was like early in Mars’ history and whether it was habitable for life.

“This information will be used to help us define the best spots to collect rock samples for future return to Earth.

“Laboratory analyses of such samples on Earth will enable us to search for morphological and chemical signatures of ancient life on Mars and also answer key questions about Mars’ geological evolution.”

Professor Mark Sephton, also from Imperial, will help identify samples of Mars that could contain evidence of past life.

He said: “I hope that the samples we select and return will help current and future generations of scientists answer the question of whether there was ever life on the Red Planet.

“With one carefully chosen sample from Mars, we could discover that the history of life on the Earth is not unique in the Universe.”

Read more about Mars exploration:

- Astrogeology: How are we looking for life on Mars?

- Move over, Mars: why we should look further afield for future human colonies

- Does the Red Planet harbour life? Here’s what we know

Professor Caroline Smith, from the Natural History Museum, will study the mineralogy and geochemistry of the different rocks found in the crater.

Dr Keyron Hickman-Lewis, who is preparing to join the museum, will study the palaeoenvironments of sedimentary horizons exposed in Jezero crater and the potential for signatures of ancient microbial life preserved within.

Dr Hickman-Lewis said: “Mars probably presents our best chance of finding life elsewhere in the Solar System, and the fact that Mars 2020 plans to prepare samples for eventual return to Earth gives us a unique opportunity to discover traces of that life."

NASA’s Perseverance rover and the recently launched UAE Hope mission will blaze a trail ahead of the launch of the UK-built Rosalind Franklin rover, due to blast into space in 2022.

The Rosalind Franklin rover, which was built by Airbus in Stevenage, Hertfordshire, will be able to drill 2m below the surface, gathering samples from regions not affected by radiation.

Perseverance will carry instruments geared to search for the carbon building blocks of life and other microbes and to reconstruct the geological history of the Red Planet.

The instruments will analyse samples from the surface, with selected samples collected by drilling down to 7cm and then sealed in special tubes and stored on the rover.

When the rover reaches a suitable location, it will drop the tubes on the surface of Mars to be collected by a future retrieval mission, which is currently being developed.

The Sample Fetch rover, being developed by Airbus, will collect the samples and take them to the NASA Mars Ascent vehicle.

NASA and European Space Agency (ESA) scientists are planning how the samples will be curated on their return.

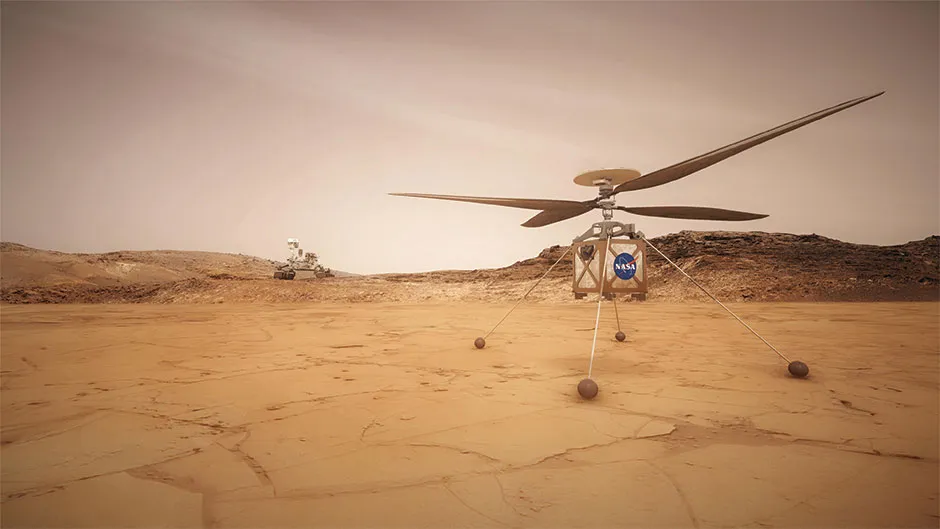

The rover also carries the Ingenuity Mars helicopter, which will fly short distances and marks the first attempt at powered, controlled flight on another planet.

If the test of the helicopter is successful, it could lead to more flying probes on other planets.

Perseverance will also trial technologies to help astronauts make future expeditions to Mars.

This includes testing a method for producing oxygen from the Martian atmosphere and identifying other resources such as subsurface water.

Sue Horne, head of space exploration at the UK Space Agency, said: “It is amazing that we are undertaking the first step of a sequence of missions to collect samples from Mars and return them to Earth.”

Reader Q&A: Why do we never see video footage from Mars?

Asked by: Richard O’Neill, Glasgow

Video footage requires much higher data transmission rates than still images, and it can take several hours for NASA to receive just one high-resolution colour image from Mars.

Engineers are looking at switching from radio to infrared communication, because the much shorter wavelength offers far higher data rates. The next generation of Mars landers may then send back HD video imagery direct from the Red Planet.

Read more: