The European Space Agency’s (ESA) exoplanet-hunting satellite Cheops has caught a glimpse of a planet deformed by the strong tidal pull of its host star for the first time.

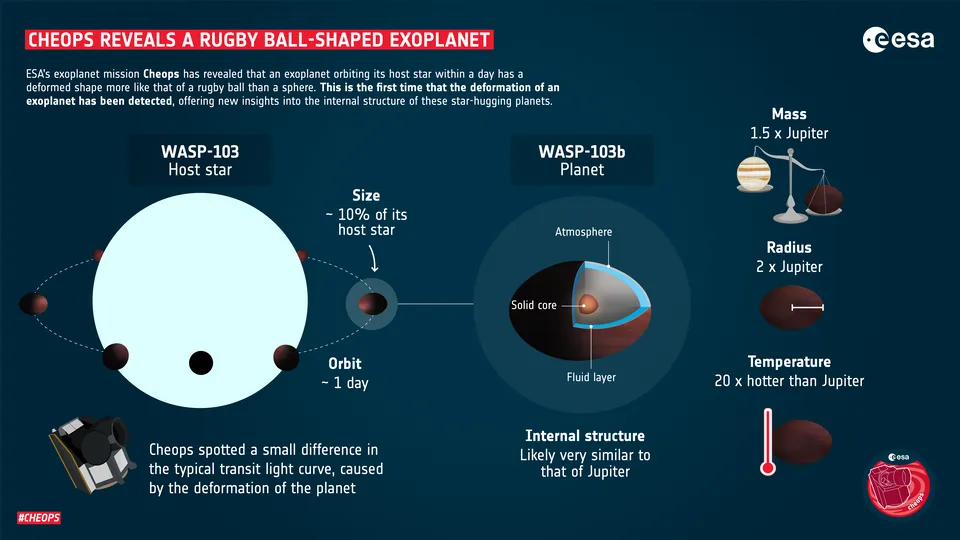

Named WASP-103b, the planet is located around 35 light-years from Earth in the constellation of Hercules and is about twice the size of Jupiter and 1.5 times its mass.

The planet is so close to its host star WASP-103, which is about 200˚C hotter and 1.7 times larger than the Sun, that it completes a full orbit in less than a day.

Astronomers have suspected that such a close proximity would cause a planet to feel a strong tidal pull from its host star, but up until now they haven’t been able to take a measurement.

Cheops measures exoplanet transits – the dip in light caused when a planet passes in front of its star. Thanks to the high precision of the measurements the satellite took of WASP-103b over multiple transits, the researchers were able to determine that the gravitational pull of its host star is strong enough to stretch the planet out into the shape of a rugby ball.

“The resistance of a material to being deformed depends on its composition,” said Susana Barros of Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço and University of Porto, Portugal, and lead author of the research.

“For example, here on Earth we have tides due to the Moon and the Sun but we can only see tides in the oceans. The rocky part doesn’t move that much. By measuring how much the planet is deformed we can tell how much of it is rocky, gaseous or water.”

The researchers were able to use the data collected by Cheops to determine WASP-103b’s Love number – a measure of how mass is distributed within a planet. The Love number for WASP-103b is similar to Jupiter, which suggests that the internal structure is similar, despite WASP-103b having twice the radius, the researchers say.

Read more about exoplanets:

- Earth may already have been spotted by 1,715 alien solar systems

- What does it mean if an exoplanet is ‘habitable’?

- Who really discovered the first exoplanet?

The team now hope to study the planet further using observations taken by Cheops and the newly launched James Webb Space Telescope to shed further light on its internal structure.

“It’s incredible that Cheops was actually able to reveal this tiny deformation,” said Jacques Laskar of Paris Observatory, Université Paris Sciences et Lettres, and co-author of the research.

“This is the first time such analysis has been made, and we can hope that observing over a longer time interval will strengthen this observation and lead to better knowledge of the planet’s internal structure."