Observing the birth of the first stars and galaxies has been a sought-after goal of astronomers for decades. And now a worldwide team, co-led by the Universities of Cambridge and Stellenbosch, South Africa, has developed a technique to observe and study these ancient starsby looking through the clouds of fog that filled the Universe around 378,000 years after the Big Bang.

The team’s research, part of the REACH (Radio Experiment for the Analysis of Cosmic Hydrogen) experiment, will allow astronomers to observe the earliest stars by studying these primordial hydrogen clouds with a radio telescope – in the same way we might define a landscape by looking at shadows in the fog.

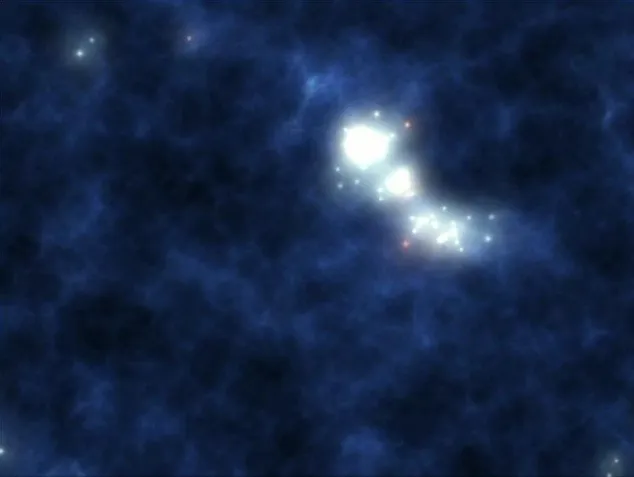

“At the formation of the first stars, the Universe was mostly empty and composed mostly of hydrogen and helium. Because of gravity, these elements eventually came together and the conditions were right for nuclear fusion, which is what formed the first stars," said lead researcher Dr Eloy de Lera Acedo, from Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory.

"They were surrounded by clouds of so-called neutral hydrogen, which absorb light really well, so it’s hard to detect or observe the light behind the clouds directly.”

The REACH team has had to overcome issues relating to radio telescope observations – where distortions are introduced to the signal received – which can completely obscure a cosmological signal of interest.

Furthermore, the elusive signal the team is searching for is expected to be around 100,000 times weaker than other radio signals coming from the sky – for example, those from our own Galaxy.

To study the cosmic dawn, the team are looking at the ‘21cm line’ (also known as the Hydrogen line, or H I line) – an electromagnetic radiation signature from hydrogen in the early Universe.

They are looking for a radio signal that measures the contrast between the radiation from the hydrogen and the radiation behind the hydrogen fog.

The REACH researchers have used simulations to mimic a real observation using multiple antennas – when earlier observations have relied on a single antenna – to improve the reliability of the data.

“We forgot about traditional design strategies and instead focused on designing a telescope suited to the way we plan to analyse the data – something like an inverse design,” said de Lera Acedo. “This could help us measure things from the cosmic dawn and into the epoch of reionisation, when hydrogen in the Universe was reionised.”

With the research method in place, the first observations from the REACH telescope are expected later this year. Meanwhile, its construction is being finalised at the Karoo radio reserve in South Africa, a location which boasts excellent conditions for radio observations.

Read more about space: