Intensive farming practices provide the perfect environment for bacteria and viruses to spread across the world and increase the risk of epidemics, scientists have said.

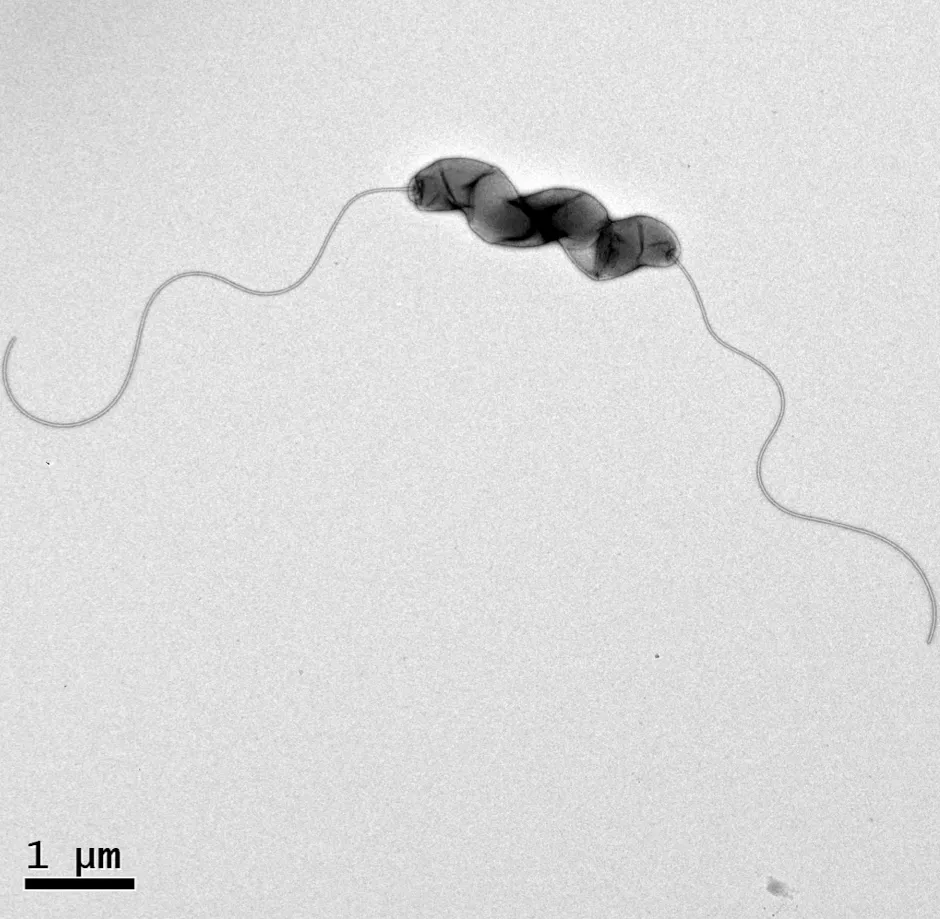

Their warning comes following a genetic analysis of the bacteria Campylobacter jejuni, which is commonly found in farmed cattle.

The bug is also considered to be the most common bacterial cause of human gastroenteritis, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Read more epidemiology stories:

- Transmission of viruses from animals to humans is'a direct result of our actions'

- Epidemiology: the history of disease and epidemics

- How to survive a plague: The story of how activists and scientists tamed AIDS

In a new UK-led study, the researchers have warned the techniques used in intensive farming are increasing the likelihood of animal-to-human transmission of pathogens like Campylobacter, posing a global public health risk.

Professor Sam Sheppard, from the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath, said: “There are an estimated 1.5 billion cattle on Earth, each producing around 30kg of manure each day; if roughly 20 per cent of these are carrying Campylobacter, that amounts to a huge potential public health risk.

“Over the past few decades, there have been several viruses and pathogenic bacteria that have switched species from wild animals to humans: HIV started in monkeys; H5N1 came from birds; now COVID-19 is suspected to have come from bats.

“Our work shows that environmental change and increased contact with farm animals has caused bacterial infections to cross over to humans too.”

Prof Sheppard said the instances of the previous epidemics should be a “wake-up call to be more responsible about farming methods”.

Campylobacter can be found in the faeces of chickens, pigs, cattle and wild animals and is estimated to be present in the excrement of 20 per cent of cattle worldwide.

While infections caused by the bacteria are generally mild, it can be fatal among infants and young children, the elderly, and people who are immuno-suppressed.

The bug is resistant to antibiotics because the medicines are used in farmed animals to help prevent disease outbreaks.

The researchers studied the genetic evolution of Campylobacter and found strains specific to cattle emerged in the 20th Century, coinciding with large increases in farmed cattle numbers during that time.

The authors believe changes in anatomy, physiology and diet of the cattle caused by industrialised agriculture triggered genetic changes in the bacteria that enabled it to cross the species barrier and infect humans.

Professor Dave Kelly, from the department of molecular biology and biotechnology at the University of Sheffield, said: “Human pathogens carried in animals are an increasing threat and our findings highlight how their adaptability can allow them to switch hosts and exploit intensive farming practices.”

The research is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

How do viruses jump from animals to humans?

Every animal species hosts unique viruses that have specifically adapted to infect it. Over time, some of these have jumped to humans – these are known as ‘zoonotic’ viruses.

As our populations grow, we move into wilder areas, which brings us into more frequent contact with animals we don’t normally have contact with. Viruses can jump from animals to humans in the same way that they can pass between humans, through close contact with body fluids like mucus, blood, faeces or urine.

Because every virus has evolved to target a particular species, it’s rare for a virus to be able to jump to another species. When this does happen, it’s by chance, and it usually requires a large amount of contact with the virus.

Initially, the virus is usually not well-suited to the new host and doesn’t spread easily. Over time, however, it can evolve in the new host to produce variants that are better adapted.

When viruses jump to a new host, a process called zoonosis, they often cause more severe disease. This is because viruses and their initial hosts have evolved together, and so the species has had time to build up resistance. A new host species, on the other hand, might not have evolved the ability to tackle the virus. For example, when we come into contact with bats and their viruses, we may develop rabies or Ebola virus disease, while the bats themselves are less affected.

It’s likely that bats were the original source of three recently emerged coronaviruses: SARS-CoV (2003), MERS-CoV (2012) and SARS-CoV-2, the cause of the 2019-20 coronavirus outbreak. All of these jumped from bats to humans via an intermediate animal; in the case of SARS-CoV-2, this may have been pangolins, but more research is needed.

Read more: