Remains of a teenage girl who lived around 9,000 years ago have been discovered at a burial site in Peru alongside “a well-stocked, big-game hunting toolkit”.

Researchers say the findings, published in the journal Science Advances, challenges the hypothesis that prehistoric hunting was exclusively the domain of men, with women taking on the role of foragers.

“An archaeological discovery and analysis of early burial practices overturns the long-held ‘man-the-hunter’ hypothesis," said Dr Randy Haas, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of California, Davis, US, and the lead author on the study.

“Labour practices among recent hunter-gatherer societies are highly gendered, which might lead some to believe that sexist inequalities in things like pay or rank are somehow ‘natural’. But it’s now clear that sexual division of labour was fundamentally different – likely more equitable – in our species’ deep hunter-gatherer past.”

Read more about archaeology:

- Did Neanderthals have a society?

- 48,000-year-old arrowheads found in Sri Lankan cave

- Ancient humans arrived in Europe 'far earlier than previously thought'

The remains of the female hunter were found in 2018 during archaeological excavations at a high-altitude site called Wilamaya Patjxa in Peru.

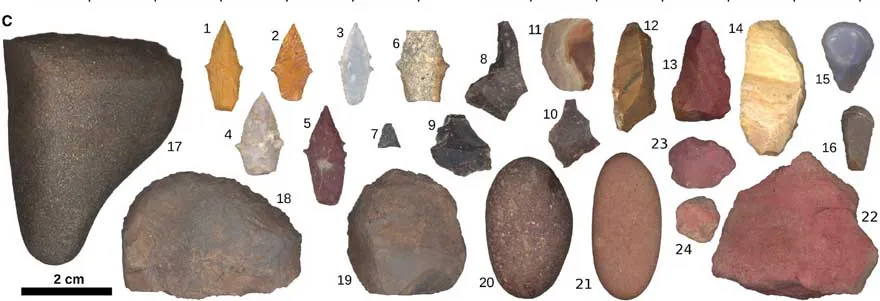

According to the researchers, the burial contains a “comprehensive array of hunting and animal processing tools that together provided unusually robust support for her hunter status”.

These tools include “stone projectile points for felling large animals, a knife and flakes of rock for removing internal organs, and tools for scraping and tanning hides”.

The sex of the human remains was confirmed by a protein analysis of the dental remnants while bone examination suggests she may have been between aged 17 to 19 at the time of her death.

Following what they describe as a “surprising discovery”, the researchers then looked at archaeological records of other burial sites throughout North and South America.

They found evidence of 27 individuals buried with big-game hunting tools – 11 female and 16 male.Based on their findings, the team suggests that between 30 per cent and 50 per cent of big-game hunters who lived more than 10,000 years ago in the Americas may have been women.

“Our findings have made me rethink the most basic organisational structure of ancient hunter-gatherer groups, and human groups more generally," Prof Haas said.

“Among historic and contemporary hunter-gatherers, it is almost always the case that males are the hunters and females are the gatherers.

"Because of this – and likely because of sexist assumptions about division of labour in western society – archaeological findings of females with hunting tools just didn’t fit prevailing worldviews.

“It took a strong case to help us recognise that the archaeological pattern indicated actual female hunting behaviour.”

Reader Q&A: Were the Egyptian pyramids built by slaves?

Asked by: Laura Price, Cardiff

Contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t slaves who built the pyramids. We know this because archaeologists have located the remains of a purpose-built village for the thousands of workers who built the famous Giza pyramids, nearly 4,500 years ago.

I had the good fortune to work on the site in 2005-2006, and it was incredible to watch as the finds came in. There were ancient name stamps and seals – bureaucratic evidence of how the officials kept track of the huge operation to feed and house the workers. Animal bones found at the village show that the workers were getting the best cuts of meat. More than anything, there were bread jars, hundreds and thousands of them – enough to feed all the workers, who slept in long, purpose-built dormitories. Slaves would never have been treated this well, so we think that these labourers were recruited from farms, perhaps from a region much further down the Nile, near Luxor.

The labourers would have been enticed by the mix of high-quality food and the opportunity to work on such a prestigious project. Today, many of the highly experienced archaeological workmen at the pyramids come from the same region, though they are paid in hard currency, rather than prime beef and accolades.

Building the pyramids was not an easy job. The skeletons of some of the workmen show that their muscles were under a large amount of strain. But they may not have resented their jobs too much – in graffiti left near the pharaoh Khufu’s burial chamber in the Great Pyramid of Giza, they painted the name of their work crew: ‘The Friends of Khufu Gang’.

Read more: