Taking inspiration from evolution, scientists have developed a new cooling technology using the same method by which camels prevent themselves from overheating in the desert.

The way camels (and other animals, and humans, too) cool down is usually by sweating. When the internal body temperature rises, sweat glands in the skin start to produce sweat. This salty water sits on the skin, and the humidity difference between that and the dry air drives evaporation of sweat as water vapour – taking with it heat, in the form of energy.

By studying this process, scientists developed a technology that mimicked the job of sweat glands using a hydrogel, which is a gel-like material designed to hold large amounts of water. A single layer of this hydrogel could keep something cool by releasing its water over the course of around 40 hours, after which it had to be resupplied with more ‘sweat’.

Read more about animal-inspired tech:

- Owl’s flight through gusty winds could inspire new aircraft designs

- Mantis shrimp ‘clubs’ inspire a new generation of super tough materials

- Jellyfish inspire mini flying robot

To increase the amount of time that the hydrogel could keep something cool, the scientists again looked to the camel.

"Zoologists have reported that a shorn camel has to increase the water expenditure for sweating by 50 per cent in the daytime compared to the one with a natural woolly coat," said Jeffrey Grossman, a senior author of the study. This means that the animal with less fur had to produce more sweat to stay cool. So, a hydrogel without an insulating layer on top would lose water faster than one with something to act as ‘fur’.

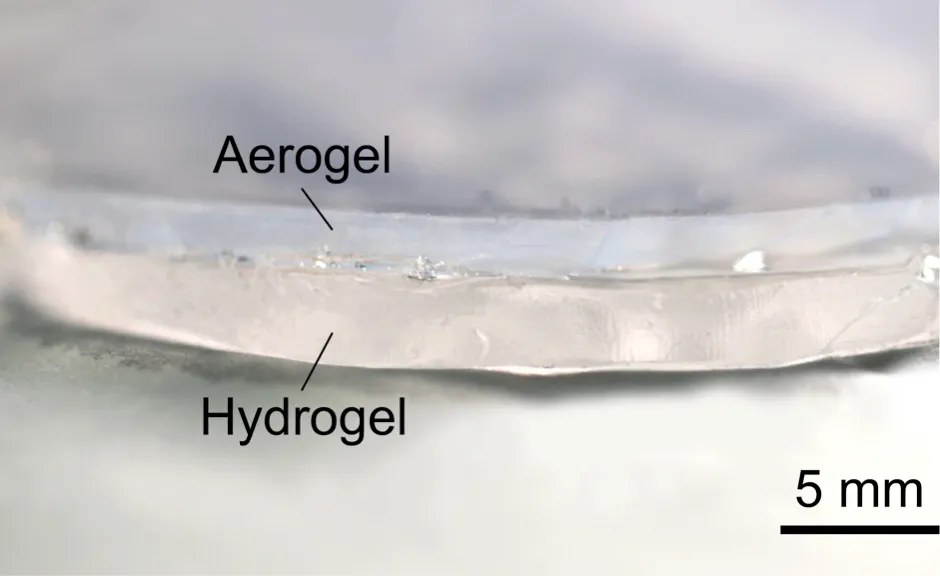

To do this, scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology designed an aerogel layer that would let the water vapour through.

"By mimicking the dual fur/gland system in camels, we designed an evaporation-insulation bilayer, which, like for the camel, allows for a significant extension of the passive evaporative cooling time for the same amount of water consumption,” said Grossman.

The team’s bilayer design kept a sample at a temperature 7˚C lower than its surroundings for 200 hours before it needed to be ‘recharged’ with more water, five times longer than then single layer approach.

Unlike cooling systems based on air conditioners and refrigerators, the hydrogel-aerogel technology doesn’t use any electricity, making it more appropriate for the millions of people around the world who have no access to electricity.

“We want this to be a green technology,” said lead author of the study, Zhengmao Lu. “Once the hydrogel is fully dried [out], it can be submerged in water (not necessarily clean water) and becomes hydrated and functional again, for multiple cooling cycles.”

More on green tech:

- UK's first hydrogen train to make its debut

- Apple: Tech giant to be carbon neutral by 2030

- Plug-in hybrid cars: Are they really the eco-friendly choice?

However, the manufacture cost of the technology is currently the bottleneck for scalability, said Grossman. But with news that the Pfizer/BioNTech coronavirus vaccine could need to be kept at -70˚C, low-cost, portable cooling technology is in demand.

“One major thing we learn in this work is the benefit of adding porous insulation, which I think can be useful for temperature regulation of the coronavirus vaccine as well,” said Lu. “Admittedly, with our current material set, where the major heat removal mechanism is still water evaporation, it is unlikely to reach such low temperatures.”

Using their discovery, Lu says a solution to the problem could be to pair dry ice with porous insulation.

“To some extent, people already do this with existing dry ice packages. To reach even lower temperatures than those, we need to optimise the design of the insulation material. At this point, we expect this might take a few years’ effort.”

Reader Q&A: Why do we sweat when we’re anxious?

Asked by: Kanika Ahuja, Winchester

This is part of our fight-or-flight response and happens when our sympathetic nervous system releases hormones, including adrenaline, which activates sweat glands.

Brain scans reveal that sniffing someone else’s panic-induced sweat lights up regions of the brain that handle emotional and social signals. So one theory is that this sweating is an evolved behaviour that makes others’ brains more alert and primed for whatever it is that’s making us anxious – handy if there’s a marauding tiger on the loose.

Read more: