Microscopic mites that live inside the pores of your skin are using the oils you produce to fuel their 'all-night' mating sessions – and that's actually a good thing. Once blamed for conditions like acne, rosacea and itchy scalps, these late-night lovers might actually be keeping our pores unblocked and free of the oils that contribute to bad skin problems.

In fact, as the tiny mites do us more good than harm, they could be considered as much a part of our daily lives as the bacteria living in our gut microbiome. But, scientists from Bangor University and the University of Reading say their new study into the tiny Demodex folliculorummites suggests the mites existence is under threat.

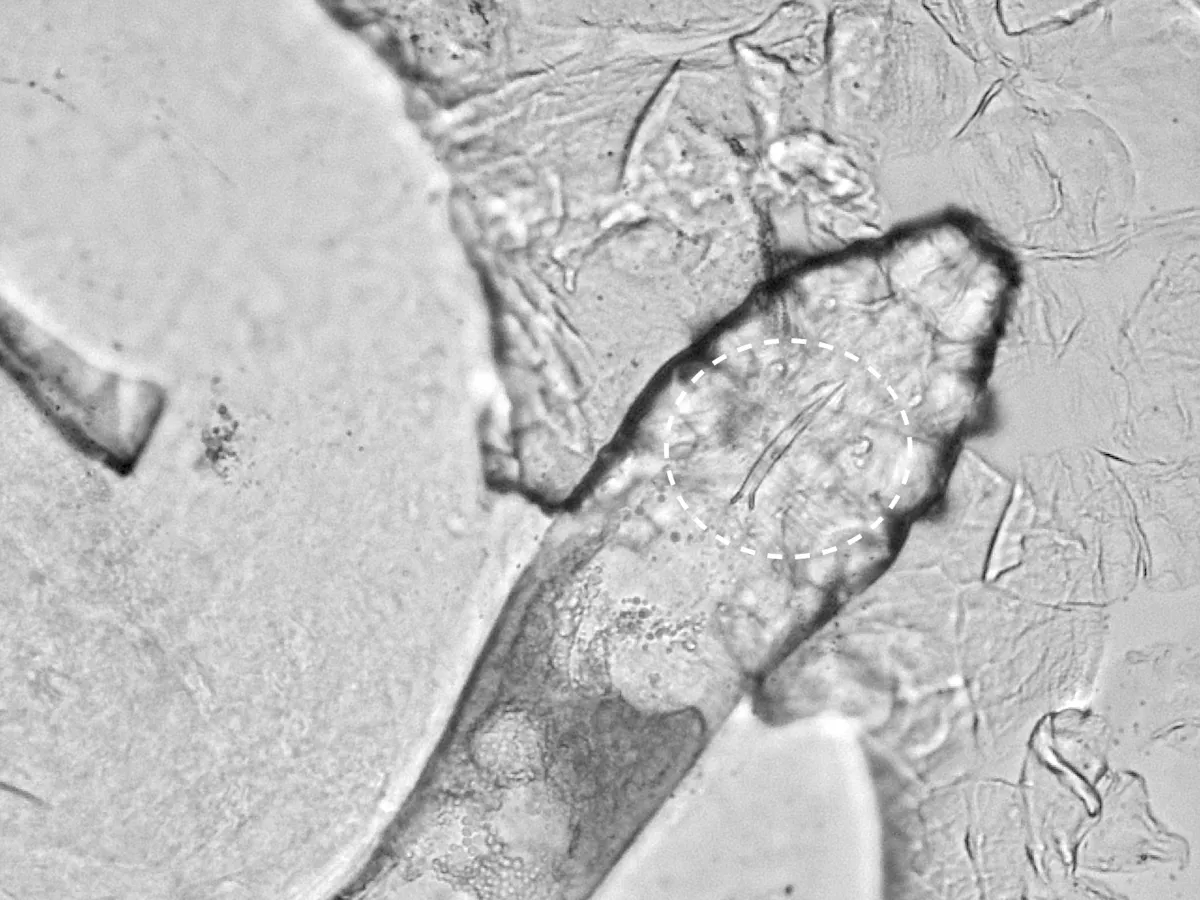

The first-ever study of the mites' DNA has revealed that their ancient relationship with humans has contributed to the loss of much of the organisms' genetic variety. Living in the follicles on our faces and nipples – the mites' preference, scientists say, though they can be found all over the body – has left them with such an isolated experience that they're fast approaching an 'evolutionary dead-end'.

With very few mite-mingling events, mating pairs have passed on the same genes for millions of years, and shed the ones that were unnecessary. As they can't protect themselves against UV radiation, the mites hide inside your pores during the day, coming out at night to feed and do the deed.

At some point, the mites lost the gene to produce melatonin, which is the chemical that nocturnal animals use to keep themselves awake at night. Luckily for the mites, melatonin is produced by glands on our skin. It's this by-product of our existence that the mites use to fuel their fecundity.

Despite the mites' relationship with us and other animals since mammals first appeared on Earth around 200 millions ago,Demodexare effectively on the path to extinction. Analysis of the mites' genome has shown that they can only be passed from mother to child (so your mites will never mix with your partner's, no matter how often you rub faces).

As generations come and go, the differences in mites' DNA become smaller in smaller. Someday, the gene pool will be so small, they'll become extinct.

The genetic analysis also dispelled one long-standing idea about the mites: that they don't have anuses and hold onto all their faeces throughout their lifetime (a short two or three weeks) until they die. This dermo-dumping, researches once supposed, could cause skin inflammation and problems like acne. But the Demodex mites don't deserve such a bad reputation.

"Mites have been blamed for a lot of things," said Dr Henk Braig, co-lead author of the new study. "[But their] long association with humans might suggest that they also could have simple but important beneficial roles, for example, in keeping the pores in our face unplugged."

Though the mites have been previously thought of as parasites, Braig and colleagues are pushing for a reassessment of their role in our lives. Their help in keeping our skin healthy means we could consider them one of our symbionts – a lifelong partnership between two different species that benefits both.

Can we prevent their loss? It may be too late.

"I think that we cannot stop nature, and we shouldn’t," said Dr Alejandra Perotti, co-author of the Demodex research. "However, [our] healthy skin should suffice to maintain healthy populations for generations to come."

Read more about skincare: