A team of Chinese researchers are preparing to launch a third phase of testing for a potential COVID-19 vaccine after it was found to be safe during a trial involving just over 500 people.

Scientists from a range of Chinese research institutions found the vaccine candidate provoked a double immune response by stimulating two types of antibodies and also T-cells.

The second phase of testing was conducted over the course of April, and aimed to evaluate the immune response, safety and determine the most suitable dose for a third round of trials.

Read more about ongoing coronavirus vaccine trials:

- Oxford vaccine shows 'strong antibody and T-cell immune response'

- 105 people take part in Imperial COVID-19 trial

- COVID-19 vaccine ready in first half of 2021 if trials go 'really well'

During the trial, 253 people received a high dose of the vaccine, 129 received a low dose, while 126 were given a placebo.

The research, published in The Lancet, found 95 per cent of participants in the high-dose group and 91 per cent of the low-does group showed either antibody or T-cell immune response 28 days after vaccination.

Because there is still no universally successful COVID-19 therapy, participants were not deliberately exposed the virus.

As a result, it is still unclear whether the level of immune response provided by the vaccine is sufficient to protect against infection from the coronavirus.

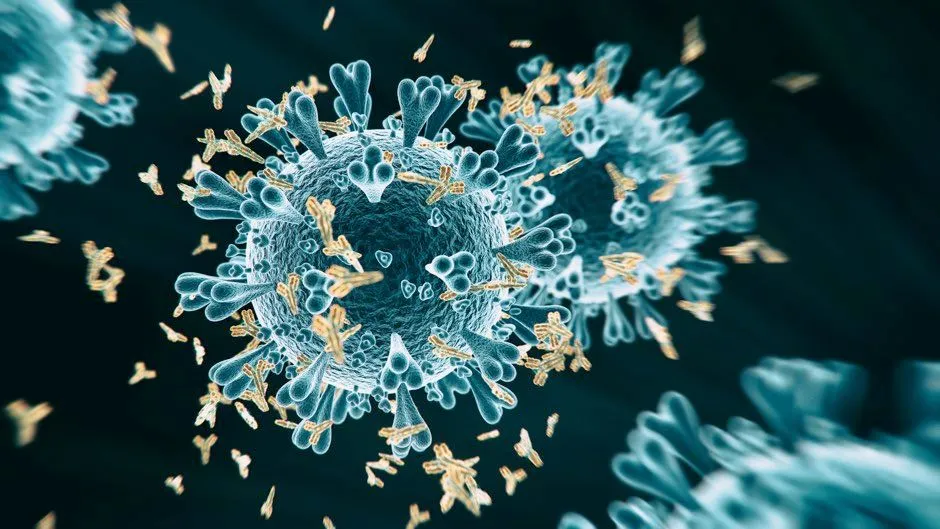

These two immune responses work together to resist infection – antibodies are found in bodily fluids and tackle viruses by either neutralising them or binding to them to flag them up to other immune cells.

T-cells can recognise and kill a cell that has been hijacked by a virus and turned into a little factory generating new viruses – acting as a backstop if viruses do manage to get past the antibodies.

In the study, T-cell responses were found in 90 per cent of the high-dose participants and 88 per cent of the low-dose participants. It was found that the vaccine generated a neutralising antibody response in 59 per cent of high-dose and 47 per cent of low-dose participants.

It generated a binding antibody response in 96 per cent of the high-dose and 97 per cent of the low-dose group, while he participants in the placebo group showed no antibody increase from baseline.

During phase two of testing, 24 people in the high-dose group had a severe reaction to the vaccine, one in the low-dose group and two people in the placebo group – the most common severe reaction was fever.

Read the latest coronavirus news:

- Synairgen drug 'prevents 79 per cent' of coronavirus cases progressing

- COVID-19: Scientists predict 3,500 deaths due to late cancer diagnosis

- Coronavirus: physical distancing and closures 'a key component' in decreasing number of new cases

Professor Feng-Cai Zhu, of China’s Jiangsu Provincial Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, said: “This is an important step in evaluating this early-stage experimental vaccine and phase-three trials are now under way.”

Just 13 per cent of those involved were over the age of 55, and the third round of testing is expected to include much greater numbers of older people.

Professor Wei Chen, from the Beijing Institute of Biotechnology, says: “Since elderly individuals face a high risk of serious illness and even death associated with COVID-19 infection, they are an important target population for a COVID-19 vaccine.

“It is possible that an additional dose may be needed in order to induce a stronger immune response in the elderly population, but further research is under way to evaluate this.”

The researchers also emphasised it is not clear if any immune response may last, as participants were last tested just 28 days after receiving their dose of the vaccine.

How do scientists develop vaccines for new viruses?

Vaccines work by fooling our bodies into thinking that we’ve been infected by a virus. Our body mounts an immune response, and builds a memory of that virus which will enable us to fight it in the future.

Viruses and the immune system interact in complex ways, so there are many different approaches to developing an effective vaccine. The two most common types are inactivated vaccines (which use harmless viruses that have been ‘killed’, but which still activate the immune system), and attenuated vaccines (which use live viruses that have been modified so that they trigger an immune response without causing us harm).

A more recent development is recombinant vaccines, which involve genetically engineering a less harmful virus so that it includes a small part of the target virus. Our body launches an immune response to the carrier virus, but also to the target virus.

Over the past few years, this approach has been used to develop a vaccine (called rVSV-ZEBOV) against the Ebola virus. It consists of a vesicular stomatitis animal virus (which causes flu-like symptoms in humans), engineered to have an outer protein of the Zaire strain of Ebola.

Vaccines go through a huge amount of testing to check that they are safe and effective, whether there are any side effects, and what dosage levels are suitable. It usually takes years before a vaccine is commercially available.

Sometimes this is too long, and the new Ebola vaccine is being administered under ‘compassionate use’ terms: it has yet to complete all its formal testing and paperwork, but has been shown to be safe and effective. Something similar may be possible if one of the many groups around the world working on a vaccine for the new strain of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is successful.

Read more: