A new coronavirus variant found in Bristol may be able to infect people who have already had COVID-19 or who have been vaccinated. However, the jabs will still protect against severe disease, experts have said.

The Bristol variant contains the E484K mutation, a genetic change also found in the South African and Brazilian variants.

Laboratory studies have shown that viruses with this mutation are able to escape human defences, making them more efficient at evading natural and vaccine-triggered immunity.

As of Thursday 11 February, Public Health England (PHE) said it had identified 22 cases of the Bristol variant.Another variant has been identified in Liverpool with the same mutation, taking the total number of cases with the new coronavirus variants to 78.

Read more about COVID-19 variants:

- Pfizer vaccine appears to be effective against UK coronavirus variant

- COVID-19: Moderna vaccine 'effective against new variants'

“There are data suggesting that this mutation may reduce the efficiency of immune responses against the virus," said Dr Jonathan Stoye, group leader of the Retrovirus-Host Interactions Laboratory at the Francis Crick Institute. “It is this change that makes the South African variant that we’ve heard so much about such a danger.

“We hear a lot about trying to keep the South African variants out but what appears to be happening in Bristol and Liverpool is that the same mutation is occurring, which might give these viruses the same properties as the viruses that we were trying to keep out.

“It is the same basic reason we’re afraid that this virus will escape some of the immune response that is generated against both the vaccine strains and previous infections.”

Latest figures from PHE revealed there are currently 202 cases of the South African variant in the UK. However, experts said that even if coronavirus vaccines are less effective in preventing a person from becoming infected with variant, the current jabs in use could still prevent severe disease and cut hospital admissions.

“The only thing that matters is whether the vaccine stops people from going to hospital or not," said Dr David Matthews, virologist at the University of Bristol. “As far as we can tell, none of the viruses that are emerging can do the thing that you dread – which is that it can both evade the vaccine and still put people in hospital – because that’s really the only thing we need to worry about.

“So they [the variants] are of concern, in the sense that we need to monitor the virus – because we need to know as soon as possible if a version of the virus has emerged that can evade the vaccine and still put people in hospital.

“But at the moment there’s no evidence that people who have had the vaccine are getting hospitalised with new versions of the virus.”

To contain the spread of infections from mutated variants, the Government has introduced surge testing in parts of Worcestershire, Bristol, south Gloucestershire, Manchester and London. However, some experts say that even with best efforts, mutations of concern could spontaneously emerge elsewhere.

“Even if we are highly successful in Bristol and Liverpool, the mutation could crop up elsewhere. And that doesn’t mean that it has escaped from either of those places," said Simon Clarke, associate professor in cellular microbiology at the University of Reading.

He said until there are new vaccines available that deal with coronavirus variants, which may be in early autumn, “we do need to keep these [variants] suppressed as much as we can."

How do scientists develop vaccines for new viruses?

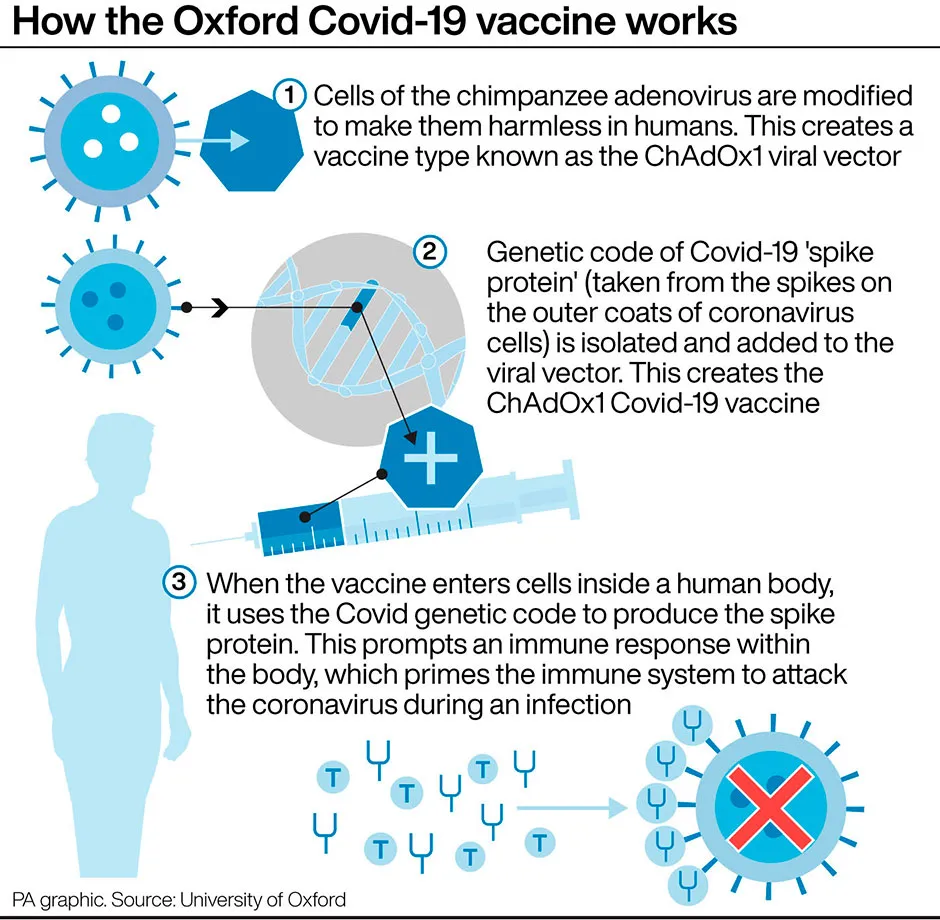

Vaccines work by fooling our bodies into thinking that we’ve been infected by a virus. Our body mounts an immune response, and builds a memory of that virus which will enable us to fight it in the future.

Viruses and the immune system interact in complex ways, so there are many different approaches to developing an effective vaccine. The two most common types are inactivated vaccines (which use harmless viruses that have been ‘killed’, but which still activate the immune system), and attenuated vaccines (which use live viruses that have been modified so that they trigger an immune response without causing us harm).

A more recent development is recombinant vaccines, which involve genetically engineering a less harmful virus so that it includes a small part of the target virus. Our body launches an immune response to the carrier virus, but also to the target virus.

Over the past few years, this approach has been used to develop a vaccine (called rVSV-ZEBOV) against the Ebola virus. It consists of a vesicular stomatitis animal virus (which causes flu-like symptoms in humans), engineered to have an outer protein of the Zaire strain of Ebola.

Vaccines go through a huge amount of testing to check that they are safe and effective, whether there are any side effects, and what dosage levels are suitable. It usually takes years before a vaccine is commercially available.

Sometimes this is too long, and the new Ebola vaccine is being administered under ‘compassionate use’ terms: it has yet to complete all its formal testing and paperwork, but has been shown to be safe and effective. Something similar may be possible if one of the many groups around the world working on a vaccine for the new strain of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is successful.

Read more: