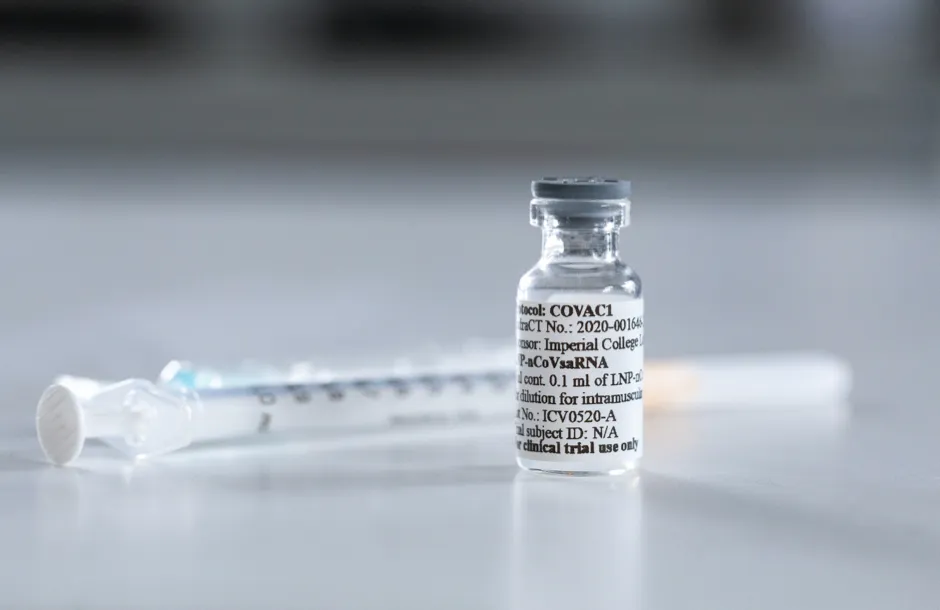

A coronavirus vaccine being developed by Imperial College London could be approved for use by the middle of next year, an expert has said.

Professor Robin Shattock, who is leading the university’s COVID-19 vaccine effort, told the European Parliament trials are showing promising results.

He said human volunteers seem to be “responding well” to the vaccine and the aim is to launch a large 20,000-person trial before the end of the year.

Read more about developing a COVID-19 vaccine:

- Coronavirus vaccine ready for end of year for some, says England's chief medical officer

- Oxford coronavirus vaccine: Trials resume after pause

- COVID-19: Who should get a vaccine first?

If trials continue to show promising results, Shattock explained, then international trials will begin later this year with potential approval for the vaccine by mid-2021.

He added that if their vaccine is successful, it will be distributed through a new social enterprise – VacEquity Global Health (VGH) – and the aim will be to distribute it as widely as possible, including to low and middle-income countries.

For the UK and low-income countries abroad, Imperial and VGH will waive royalties and charge only modest cost-plus prices.

We are all in a race against the virus and not each other. The more vaccines that pass the finishing line, the greater choice we have for global access

Professor Robin Shattock, Imperial College London

Shattock also spoke about the natural immunity, how much protection a vaccine might provide, and virus mutations.

“The numbers of reinfection are currently extremely low and there is no evidence to suggest that reinfection is associated with serious disease," said Shattock.

“We’re not seeing repeated episodes of serious disease. We can be confident that natural immunity in the majority does provide some protection against severe disease.

“We are at a stage where we don’t know if any of these vaccines work and so our understanding of the duration of protection that any vaccine may deliver is at best, guess work at this stage.”

“I think we cannot rule out the possibility that there may be requirement for repeat boosting, particularly for vulnerable populations, potentially on an annual basis,” said Shattock.

He added that one piece of good news was that the virus appears to be showing very little change, or mutation, at this stage.

There is therefore “no evidence any of the vaccines currently in development will be rendered redundant by changes in the virus but this needs to be monitored very carefully.”

The latest coronavirus news:

- COVID-19: Around 20 per cent of cases are asymptomatic

- Shoebox-sized coronavirus test kit gives results in just 90 minutes

- Rehab vital for 'long COVID' patients, says expert

Giving evidence at a joint hearing of the European Parliament’s Industry, Research and (ITRE) and Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI) Committees, he also highlighted how European funding and collaboration is essential when tackling global health challenges.

“We have been working with a number of EU colleagues from this programme on the development, evaluation and production of our COVID-19 vaccine," said Shattock.

“The lessons learned with prototype RNA vaccines from the EAVI2020 project have informed design elements that we are now applying to COVID-19.”

Shattock said co-ordinated action across Europe and the world will be crucial as people move on to the next stage of the pandemic and look to deal with other current and future global challenges.

“We are all in a race against the virus and not each other.

“The more vaccines that pass the finishing line, the greater choice we have for global access,” he told MEPs.

How do scientists develop vaccines for new viruses?

Vaccines work by fooling our bodies into thinking that we’ve been infected by a virus. Our body mounts an immune response, and builds a memory of that virus which will enable us to fight it in the future.

Viruses and the immune system interact in complex ways, so there are many different approaches to developing an effective vaccine. The two most common types are inactivated vaccines (which use harmless viruses that have been ‘killed’, but which still activate the immune system), and attenuated vaccines (which use live viruses that have been modified so that they trigger an immune response without causing us harm).

A more recent development is recombinant vaccines, which involve genetically engineering a less harmful virus so that it includes a small part of the target virus. Our body launches an immune response to the carrier virus, but also to the target virus.

Over the past few years, this approach has been used to develop a vaccine (called rVSV-ZEBOV) against the Ebola virus. It consists of a vesicular stomatitis animal virus (which causes flu-like symptoms in humans), engineered to have an outer protein of the Zaire strain of Ebola.

Vaccines go through a huge amount of testing to check that they are safe and effective, whether there are any side effects, and what dosage levels are suitable. It usually takes years before a vaccine is commercially available.

Sometimes this is too long, and the new Ebola vaccine is being administered under ‘compassionate use’ terms: it has yet to complete all its formal testing and paperwork, but has been shown to be safe and effective. Something similar may be possible if one of the many groups around the world working on a vaccine for the new strain of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is successful.

Read more: