Why is the Government advising us to wash our hands?

Coronavirus is a respiratory illness, meaning it is mostly spread through virus-laden droplets from coughs and sneezes. If you don’t catch your coughs and sneezes in a tissue and safely dispose of it, the virus can end up on surfaces. If someone else touches that contaminated surface, the virus can transfer onto their hand.

If you have the virus on your hands, you can infect yourself by touching your eyes, mouth or nose. You might think that you don’t touch your face very often, but it’s much more than you realise. A 2015 study found that people touch their faces an average of 23 times an hour.

While washing your hands is useful in preventing yourself from getting infected, this is not the main reason the Government recommends it.

“It’s all about stopping the spread,” says Sally Bloomfield, honorary professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “When it comes to stopping the spread of the serious infection in this country, the public have a huge role to play.”

Does soap kill coronavirus?

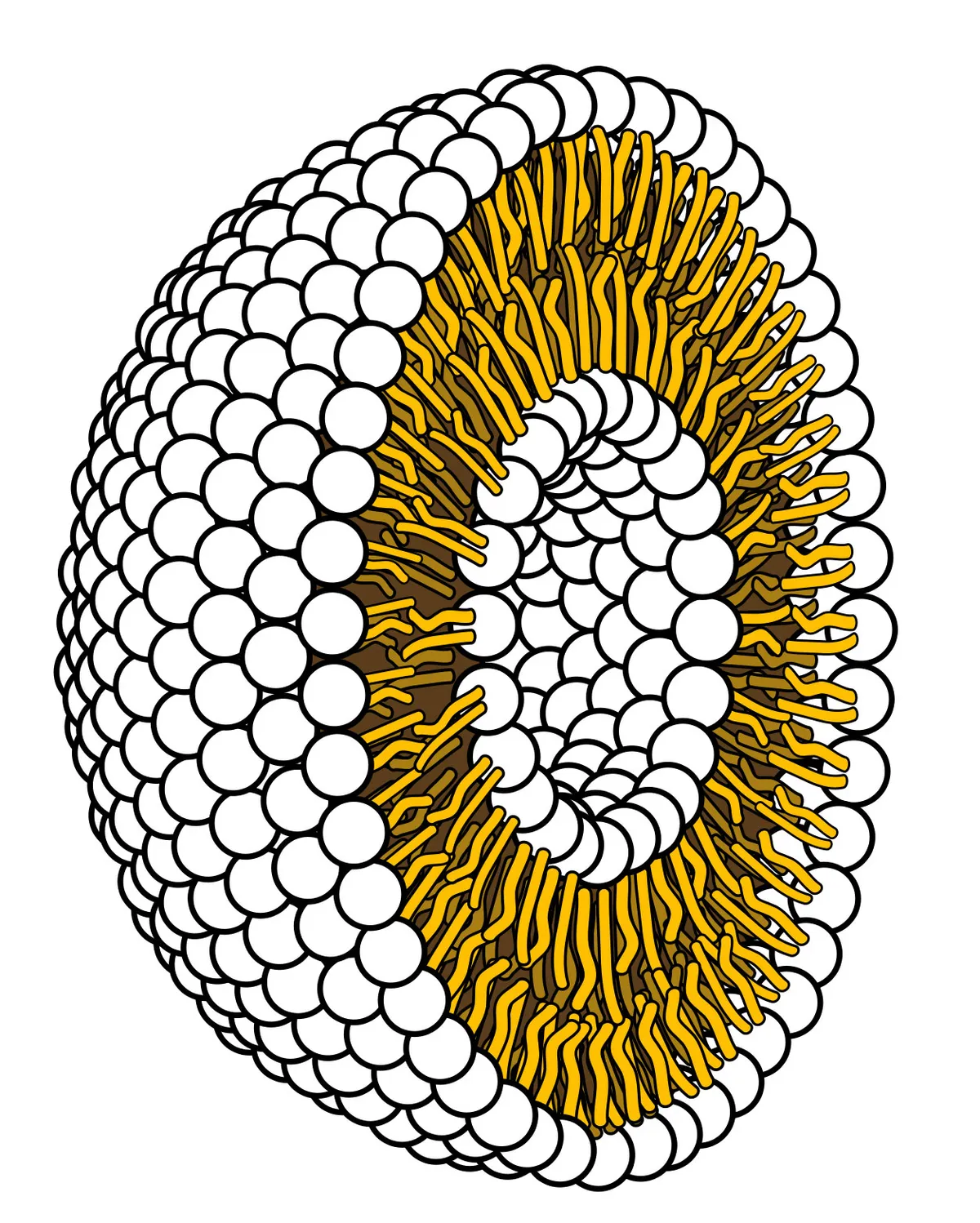

Coronavirus is an ‘enveloped virus’. This means it has a protective outer layer known as a ‘lipid bilayer’. The molecules making up this layer are shaped like a tadpole, with a water-loving (hydrophilic) round head and a water-hating (hydrophobic) tail.

These molecules arrange themselves into a ‘bilayer’: two layers piled on top of each other into a sheet, with tails pointing inwards and heads pointing outwards.

The molecules are pulled closely into each other to protect the hydrophobic tails from the water in your respiratory droplets when you cough or sneeze.

The hydrophilic heads are very ‘sticky’, meaning the virus is very effective at sticking to your hands – perfect for a microbe that’s trying very hard to infect you.

Soap molecules also have this tadpole structure, which is what makes it so useful. When you have something oily on your hands, running water won’t get rid of it. Add soap to your hands – the hydrophobic tail will cling to the oil, and the hydrophilic head will stick to the water. Now, the oil will come straight off.

Because the soap molecules are so similar to the ones making up the outer layer of the virus, the molecules in the lipid bilayer are as strongly attracted to soap molecules as they are to each other.

This disrupts the neatly-ordered shell around the virus, dissolving it in the running water and killing the virus.

Read more about coronavirus:

- Coronavirus: is it a cause for panic?

- Coronavirus: aggressive 'L type' strain affecting 70 per cent of cases

- Coronavirus breakthrough: scientists grow virus in laboratory

Does antibacterial hand sanitiser kill viruses?

Yes. Alcohol-based hand sanitiser will kill viruses if soap and water are not available. Alcohol is an antiseptic and can kill enveloped viruses such as coronavirus, but make sure it contains 60 to 95 per cent alcohol.

However, if your hands are visibly dirty, you need to use soap and running water to clean the dirt off.

Will washing my hands stop me from catching coronavirus?

Unfortunately, it’s impossible to know whether any particular case of coronavirus could have been prevented by better hand-washing.

While it is possible to contract coronavirus from touching your face with virus-contaminated hands, you can also catch it directly from the coughs or sneezes of an infected person.

So, while washing your hands won’t eliminate your risk of infection, it’s a sensible and powerful safety measure.

“It’s a little bit, I think, like wearing a car seatbelt, in that it’s unlikely you’ll get infected at the present time, in the same way as you’re unlikely to have a crash when you go out in your car,” says Bloomfield. “You still go out in your car, but you always belt up your seatbelt.”

Read more from Reality Check:

- Is the Betelgeuse star about to explode?

- Late 40s: is this the most miserable time of our lives?

- 5G and the Huawei controversy: is it about more than just security?

We do, however, know that hygiene measures – hand-washing, self-isolating when ill, disposing of tissues, etc. – do prevent the spread of respiratory diseases.

Following the 2003 outbreak of SARS-CoV in Hong Kong, the Department of Health in China wanted to know how effective the government’s efforts at containing the disease were.

Since SARS-CoV (also a type of coronavirus) was a new strain, there was no benchmark for how far it was likely to spread. What they could measure was the incidence of seasonal respiratory illnesses such as the flu.

Compared to the average numbers over the previous five years, the incidence of all of these seasonal illnesses dropped. The difference was particularly clear in the months of April to June, when the public were the most stringent with their hygiene practices.

Why is it so important to stop the spread of coronavirus?

For most people, coronavirus is not a particularly dangerous illness.

“Most of us will only get something that’s really quite mild, what feels like very mild flu, and will recover,” Bloomfield explains. “But the problem is, whilst we’re infected, we are passing it on to other people.”

Hand-washing is remarkably powerful at slowing down the spread of flu-like viruses, as mathematician Hannah Fry showed in this simulation generated for the documentary BBC Pandemic.

What slowing the spread can achieve is sometimes referred to as ‘flattening the curve’. That is, the number of cases will rise to a peak, and then drop off again.

If that process happens too quickly, many cases will occur at the same time, and the peak will be high resulting in the NHS becoming overwhelmed with cases.

However, if we can slow this process, infections may occur over a longer time period, but the peak will be much lower.

Hopefully, the number of cases at the peak will be lower than the amount the NHS can deal with.

“We want to keep that number down to a minimum so we can provide effective care where it’s needed,” says Bloomfield.

“The people we’ve got to keep it away from are the people who are vulnerable, like the elderly, people with bronchial problems, people who are immunocompromised in some way or another,” she explains, “because if they start getting it, they are at risk of very serious disease.”

How should I wash my hands?

- Start by wetting your hands. It doesn’t matter whether it’s hot or cold: a 2017 study from Rutgers University in the US found that cold water was just as effective as hot at removing E. coli.

- Next, apply either bar soap or liquid hand wash. Although there are studies which have shown that bacteria can live on the surface of a bar of soap, others have found that sharing a bar doesn’t transmit disease.

- Thoroughly rub the soap all over your hands, making sure not to miss your thumbs, between your fingers and your fingertips. This part of the process should take 20 seconds.The NHS recommends singing ‘Happy birthday’ through twice to count out 20 seconds, but you could choose any song with a 20-second chorus, such as Dolly Parton’s Jolene, or Staying Alive by the Bee Gees.

- Rinse your hands well to remove the soap. Dry them thoroughly, preferably with disposable paper towels.

- Once you have returned to your working area, or ‘safe space’, for example, desk or train seat, use a hand sanitiser.

What you do after you’ve washed your hands is important, too, says Bloomfield. “If you are, say, on an aeroplane or a train, you can wash your hands in the toilet, but you’ve then got to walk back to your seat,” she says.

“On an aeroplane, you’re going to be grabbing all the seatbacks that have been grabbed by other people. So, wash your hands or use a hand sanitiser when you get back to your ‘safe place’, so for example, when you get back to your train seat or plane seat and you’re then not going to move around.”

Can I wash my hands too much?

All of this extra hand-washing could easily dry out the skin on your hands. So, as well as washing regularly, make sure to moisturise your hands as well.

“If the skin is breaking down or raw, then the soap and alcohol disinfectants do not work as well,” says Dr Craig Shapiro, a specialist in paediatric infectious diseases in Delaware, USA, told the Washington Post. “Also, when the skin is chapped and broken, it’s uncomfortable, and people can be less likely to wash their hands to prevent transmission of germs and infection.”

Visit the BBC's Reality Check website at bit.ly/reality_check_ or follow them on Twitter@BBCRealityCheck