A coronavirus vaccine being worked on by American researchers induces a robust immune response in healthy adults, results from early phases of clinical trials suggest.

Scientists found that the vaccine, called BNT162b1, was generally well-tolerated, although some participants experienced mild to moderate side-effects.

These increased with dose level, in the seven days following vaccination, including pain at the injection site, fatigue, headache, fever and sleep disturbance.

Read the latest coronavirus news:

- Drinking in pubs creates 'perfect storm' for spreading coronavirus

- ‘Atypical COVID-19 symptoms’ common in care home patients

- COVID-19: Face shields alone ‘unlikely’ to protect hairdressers and barbers

According to an interim report of a phase 1/2 clinical trial published in Nature, the vaccine, which is being developed by Pfizer, elicited a robust immune response in participants, which increased with dose level and with a second dose.

Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 (the name of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19) were present 21 days after a single vaccination at all dose levels, and there was a substantial increase in SARS-CoV-2-neutralising antibodies seven days after the second dose was given.

Delivered via an injection directly into muscle, the BNT162b1 vaccine is made up of the genetic code for the 'receptor-binding antigen' – a section on the coronavirus's characteristic spikes that enables the virus to attach itself to our cells.

The synthetic strands of genetic code are called RNA, and BNT162b1 is one of several RNA vaccine candidates that are being studied in parallel for selection to advance to a trial of their safety and efficacy.

Once injected into muscle, the RNA self-amplifies – generating copies of itself – and elicits an immune response.

RNA vaccine platforms are generally considered safe and have facilitated the rapid development of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2.

The researchers wrote: “The clinical findings for the BNT162b1 RNA-based vaccine candidate are encouraging and strongly support accelerated clinical development, including efficacy testing, and at-risk manufacturing to maximise the opportunity for the rapid production of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine to prevent COVID-19.”

Corresponding author Judith Absalon, senior medical director at Pfizer Vaccines Clinical Research, and colleagues reported interim data from an ongoing phase 1/2 clinical study of BNT162b1.

Forty-five healthy adults – 23 men and 22 non-pregnant women – aged 18 to 55 were randomised to receive 10 micrograms, 30 micrograms or 100 micrograms of the vaccine, or a placebo.

Read more about coronavirus vaccine research:

- COVID-19 vaccine trials in China deemed safe to move to phase three

- Oxford vaccine shows 'strong antibody and T-cell immune response'

- Coronavirus vaccine: 105 people take part in Imperial COVID-19 trial

Researchers found the immune response was much stronger in the 30 microgram group than in the 10.

However, there were no notable differences in immune response between the 30 and 100 groups after one dose, and, as participants who received the 100 microgram dose also experienced greater side-effects, they did not receive a second dose.

According to the study, levels of neutralising antibodies in participants were 1.9 to 4.6 times higher than those in patients recovering from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

But the scientists warned that, although this comparison provides a benchmark for evaluating the vaccine-elicited immune response and the vaccine’s potential to provide protection, phase 3 trials are needed to determine the efficacy of the BNT162b1 vaccine.

Kathrin Jansen, senior vice president and head of vaccine research and development, Pfizer, said: “The publication of peer-reviewed data from our mRNA-based vaccine development programme against SARS-CoV-2 in a world-renowned publication like Nature provides further validation of our rapid progress toward developing a safe and effective potential vaccine to help address this current pandemic.

“We are encouraged by the overall advancement of the programme and look forward to generating additional data from our ongoing studies.”

The study is also enrolling adults aged 65–85, and later phases will prioritise the enrolment of more-diverse populations.

Pfizer and BioNTech recently selected BNT162b2 as the vaccine candidate to progress to a Phase 2/3 study, which will enrol up to 30,000 participants aged between 18 and 85.

How do scientists develop vaccines for new viruses?

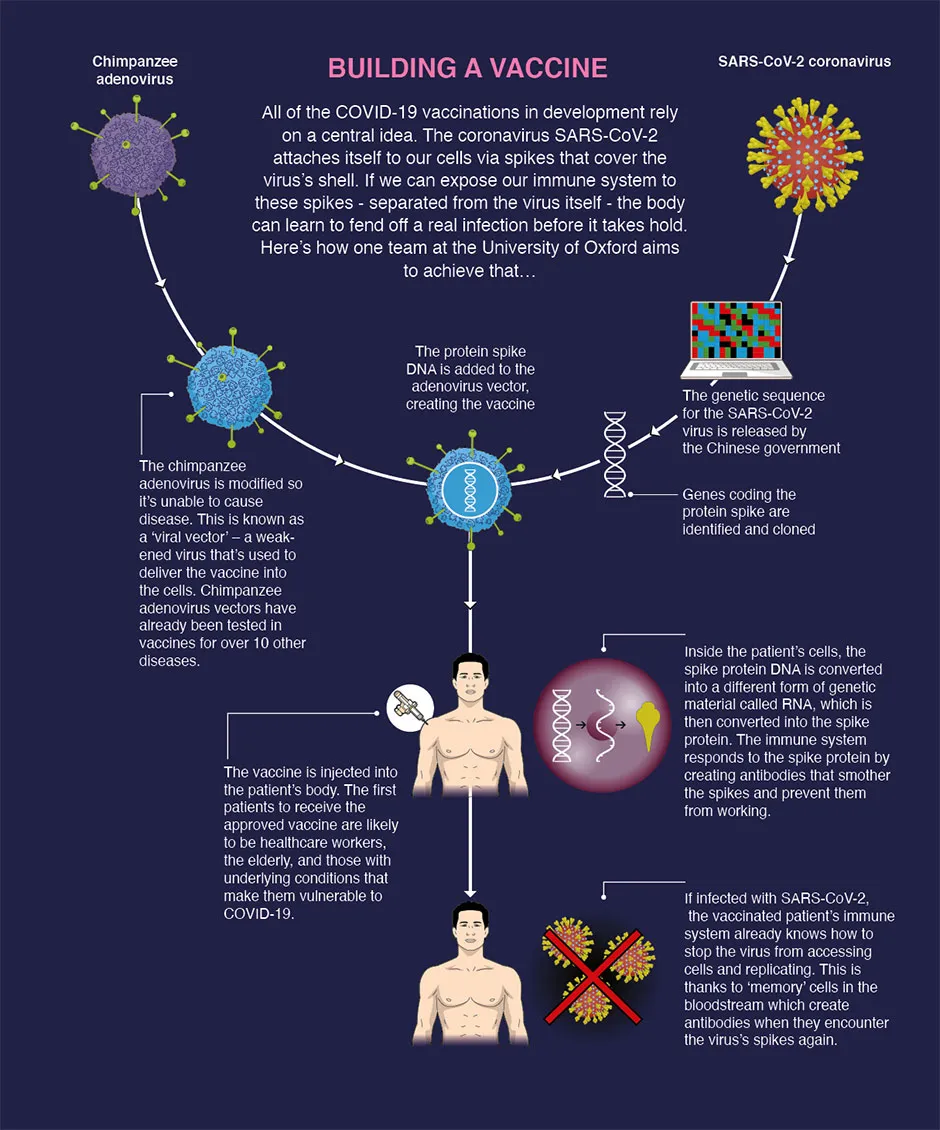

Vaccines work by fooling our bodies into thinking that we’ve been infected by a virus. Our body mounts an immune response, and builds a memory of that virus which will enable us to fight it in the future.

Viruses and the immune system interact in complex ways, so there are many different approaches to developing an effective vaccine. The two most common types are inactivated vaccines (which use harmless viruses that have been ‘killed’, but which still activate the immune system), and attenuated vaccines (which use live viruses that have been modified so that they trigger an immune response without causing us harm).

A more recent development is recombinant vaccines, which involve genetically engineering a less harmful virus so that it includes a small part of the target virus. Our body launches an immune response to the carrier virus, but also to the target virus.

Over the past few years, this approach has been used to develop a vaccine (called rVSV-ZEBOV) against the Ebola virus. It consists of a vesicular stomatitis animal virus (which causes flu-like symptoms in humans), engineered to have an outer protein of the Zaire strain of Ebola.

Vaccines go through a huge amount of testing to check that they are safe and effective, whether there are any side effects, and what dosage levels are suitable. It usually takes years before a vaccine is commercially available.

Sometimes this is too long, and the new Ebola vaccine is being administered under ‘compassionate use’ terms: it has yet to complete all its formal testing and paperwork, but has been shown to be safe and effective. Something similar may be possible if one of the many groups around the world working on a vaccine for the new strain of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is successful.

Read more: