The virus that causes COVID-19 acts like a “wolf in sheep’s clothing” by using sugars to trick its way into the human body, according to new research.

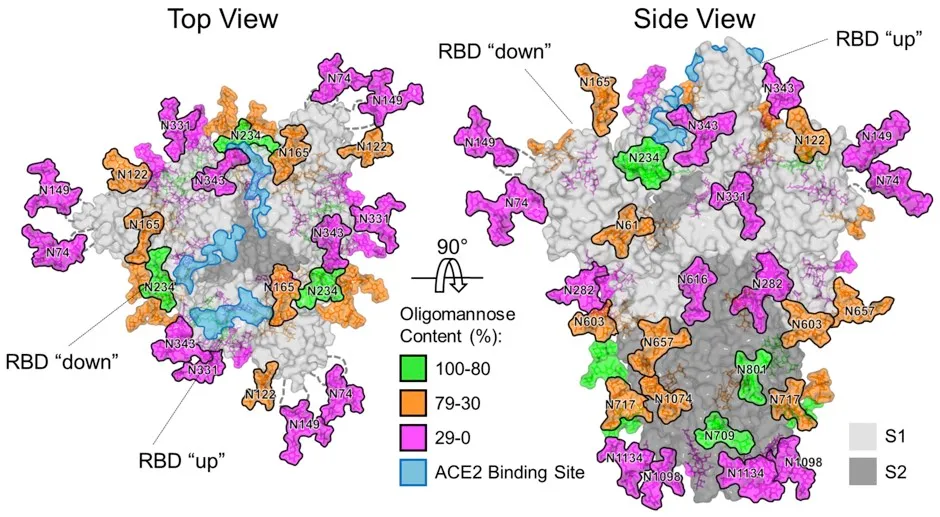

Scientists at the University of Southampton have created a model of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus that causes COVID-19 which reveals how it disguises itself to enter human cells undetected.

But they found that the virus is not as heavily protected as some others such as HIV.

Read the latest coronavirus news:

- Coronavirus test that uses lasers available 'within a year'

- Supercomputers drafted in to detect potential coronavirus treatments

- 100 days: what we now know about the coronavirus

The team, led by Professor Max Crispin, say the model will provide “crucial and encouraging” information for scientists creating a vaccine.

Prof Crispin explained that the SARS-CoV-2 virus has a large number of spikes sticking out of its surface which it uses to attach to and enter cells in the human body.

These spikes are coated in sugars, known as glycans, which disguise their viral proteins and help them evade the body’s immune system.

Prof Crispin said: “By coating themselves in sugars, viruses are like a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

“But one of the key findings of our study is that despite how many sugars there are, this coronavirus is not as highly shielded as some other viruses.

“Viruses like HIV, which hang around in one host, have to evade the immune system constantly and they have a really dense coat of glycans as a shield to the immune system.

Read more about the coronavirus pandemic:

- Should we all wear face masks?

- Coronavirus antibody tests: How they work and when we'll have them

- Corrupted Blood: what the virus that took down World of Warcraft can tell us about coronavirus

- Big tech and coronavirus: How Google and Facebook could take on the pandemic

“But in the case of the coronavirus the lower shielding by sugars attached to it may reflect that it is a ‘hit and run’ virus, moving from one person to the next.

“However, the lower glycan density means there are fewer obstacles for the immune system to neutralise the virus with antibodies. So this is a very encouraging message for vaccine development.”

The research was carried out using equipment previously provided by a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation through the Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery.

Can I get the coronavirus twice?

There have been a few stories in the press of people apparently being re-infected by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. These people reportedly became infected and hospitalised, and then were sent home once they’d tested negative for the virus. Then, days or weeks later, they tested positive again.

But this doesn’t necessarily mean that they caught the coronavirus twice.

First, during recovery from infection, a person may have very low amounts of the virus remaining in their body – low enough that our tests can’t accurately detect it. In this case, the person may be sent home on the assumption that they’re virus-free. However, their body may still be fighting the virus, and a resurgence of the virus (and symptoms) can occur, resulting in a positive test. In this case, it would just be one protracted infection, not a re-infection.

Second, we know that in most people, SARS-CoV-2 generates a strong response from the immune system. With the related coronavirus SARS-CoV, this response creates an immune memory of the virus that prevents re-infection for one to two years, and it’s likely that this is also the case for the new virus. SARS-CoV-2 also has a fairly low mutation rate, which means that it (hopefully) won’t change enough that our immune system no longer remembers it (this is what the flu virus does and why we need a new jab every year).

If this all turns out to be true, then it would suggest that re-infections are unlikely and that the cases in the news reflect testing sensitivity. However, SARS-CoV-2 is so new that we won’t know for sure until we’ve found out just how protective our immune response to the virus is, and how long it lasts.

Read more: