The first case of someone being reinfected with coronavirus has been reported by researchers in Hong Kong.

The findings could have significant implications for the development of coronavirus vaccines and what is known about natural immunity against COVID-19 – but experts have cautioned that it is too early to know whether reinfection is possible in everyone, or how severe a second infection with the virus would be in each person.

Read the latest coronavirus news:

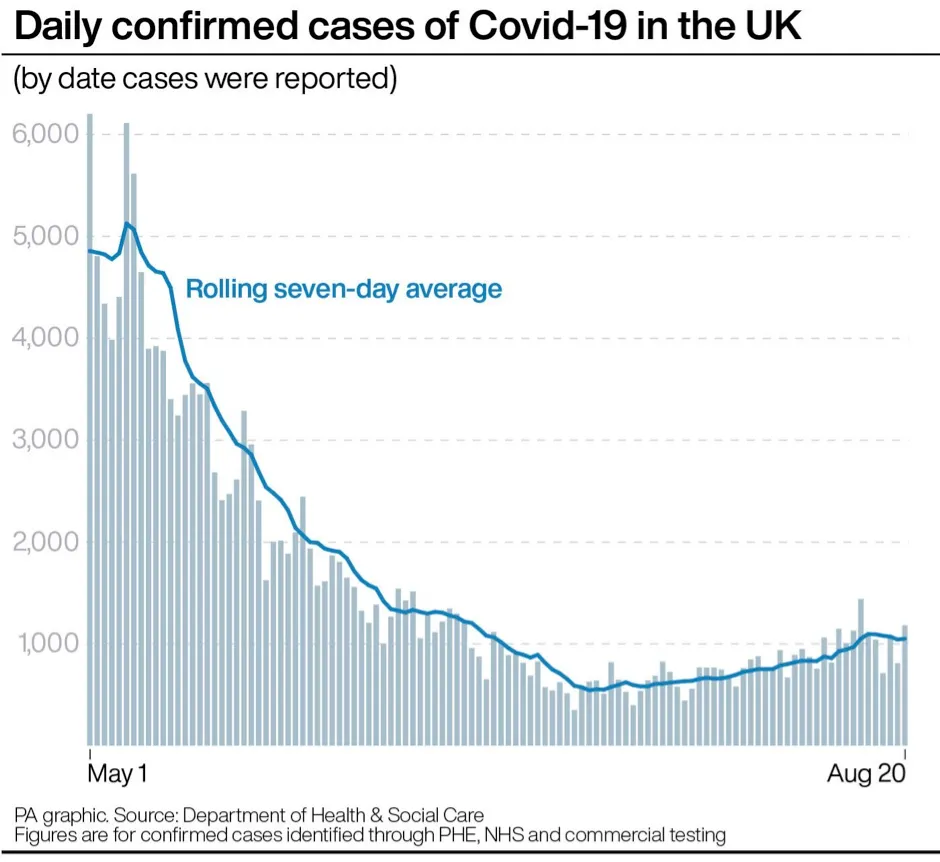

- Latest figures suggest R number is above 1.0 in England

- Coronavirus not “going to be a disease like smallpox which could be eradicated by vaccination”

- Scientists think they’ve identified how COVID-19 causes patients to lose their sense of smell

Researchers at the University of Hong Kong’s (HKU) department of microbiology said that an “apparently young and healthy patient had a second episode of COVID-19 infection which was diagnosed four and a half months after the first episode”.

They added that the case illustrates reinfection can occur a few months after recovery from the first infection.

The man had no symptoms – was asymptomatic – during the second infection which was picked up by screening tests on returning passengers at Hong Kong airport.

Genetic sequencing of the virus showed he was infected twice by different strains of COVID-19, the researchers said.

They added that the findings suggest SARS-CoV-2 may persist in the global human population, as is the case for other common-cold associated human coronaviruses, even if patients have acquired immunity via natural infection.

Someone with a second, asymptomatic case may still be able to spread the virus to others. Therefore, people with previous COVID-19 infection should comply with control measures like wearing face coverings and social distancing.

One of the researchers, Dr Kelvin Kai-Wang To, clinical associate professor in the Department of Microbiology at HKU, said: “This case shows that patients [who have] recovered from COVID-19 can get reinfected. Therefore, the immunity against COVID-19 is not lifelong. ”

He added: “Reinfection is likely occurring elsewhere. Our case was asymptomatic and was diagnosed because of screening at the airport.”

I don’t want people to be afraid. People need to understand that when they are infected, even if they have a mild infection, they do develop an immune response

Dr Maria Van Kerkhove, WHO

In a statement the university said: “Since the immunity can be short lasting after natural infection, vaccination should also be considered for those with one episode of infection.”

The study has been accepted by medical journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, but the full research is yet to be published.

Experts in the UK say it is too early to know what the single case may mean on a global scale.

Brendan Wren, professor of microbial pathogenesis, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said: “With over three million cases of COVID-19 worldwide, the first reported case of a potential reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 needs to be taken into context.

“It appears that the young and healthy adult has been reinfected with a slight SARS-CoV-2 variant from the initial infection three months previously.

“It is to be expected that the virus will naturally mutate over time. This is a very rare example of reinfection and it should not negate the global drive to develop COVID-19 vaccines.”

Dr Jeffrey Barrett, senior scientific consultant for COVID-19 Genome Project, Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: “This is certainly stronger evidence of reinfection than some of the previous reports because it uses the genome sequence of the virus to separate the two infections.

“It seems much more likely that this patient has two distinct infections than a single infection followed by a relapse (due to the number of genetic differences between the two sequences).”

But he added that it is “very hard” to make any strong inference from a single observation, and that seeing one case of reinfection is not that surprising.

“This may be very rare, and it may be that second infections, when they do occur, are not serious,” said Dr Barrett.

Read more about asymptomatic cases:

- Asymptomatic carriers should self-isolate ‘regardless of symptoms’

- Over 40 per cent of COVID-19 cases asymptomatic in Italian town study

- COVID-19 asymptomatic in over 80 per cent of cases, cruise ship study finds

Dr Maria Van Kerkhove, the WHO’s technical lead for COVID-19, said: “What we understand from the press release (about the reinfected patient) is that this may be an example of reinfection, and if you remember last week I was asked about this and I had said that in cases like this it would be good if sequencing could be done.

“And in a place like Hong Kong, where they have very strong facilities they can do that in, and in fact they have done, I understand there is a 24 nucleotide difference between the first virus and second virus.

“What I think is really important is that we put this into context. There has been more than 24 million cases reported to date and we need to look at something like this on a population level.”

She added: “But I don’t want people to be afraid, we need to ensure that people understand that when they are infected, even if they have a mild infection, they do develop an immune response.

“In this particular case, it’s very important that we look – and I haven’t read the studies so I don’t have an answer to this yet – to see if this individual developed a neutralising antibody response, which is what will protect from reinfection.”

It appears that the patient in this study was tested for antibodies only once during the first infection, which was negative. This single test is one of the limitations of the study, say the authors, as “the negative antibody test does not exclude the possibility that the patient indeed developed antibody response during the early convalescent phase for the first [infection]."

How do scientists develop vaccines for new viruses?

Vaccines work by fooling our bodies into thinking that we’ve been infected by a virus. Our body mounts an immune response, and builds a memory of that virus which will enable us to fight it in the future.

Viruses and the immune system interact in complex ways, so there are many different approaches to developing an effective vaccine. The two most common types are inactivated vaccines (which use harmless viruses that have been ‘killed’, but which still activate the immune system), and attenuated vaccines (which use live viruses that have been modified so that they trigger an immune response without causing us harm).

A more recent development is recombinant vaccines, which involve genetically engineering a less harmful virus so that it includes a small part of the target virus. Our body launches an immune response to the carrier virus, but also to the target virus.

Over the past few years, this approach has been used to develop a vaccine (called rVSV-ZEBOV) against the Ebola virus. It consists of a vesicular stomatitis animal virus (which causes flu-like symptoms in humans), engineered to have an outer protein of the Zaire strain of Ebola.

Vaccines go through a huge amount of testing to check that they are safe and effective, whether there are any side effects, and what dosage levels are suitable. It usually takes years before a vaccine is commercially available.

Sometimes this is too long, and the new Ebola vaccine is being administered under ‘compassionate use’ terms: it has yet to complete all its formal testing and paperwork, but has been shown to be safe and effective. Something similar may be possible if one of the many groups around the world working on a vaccine for the new strain of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is successful.

Read more: