A reindeer-herding community living in the Mongolian mountains are paying the “first price” for climate change due to melting ice, scientists have said.

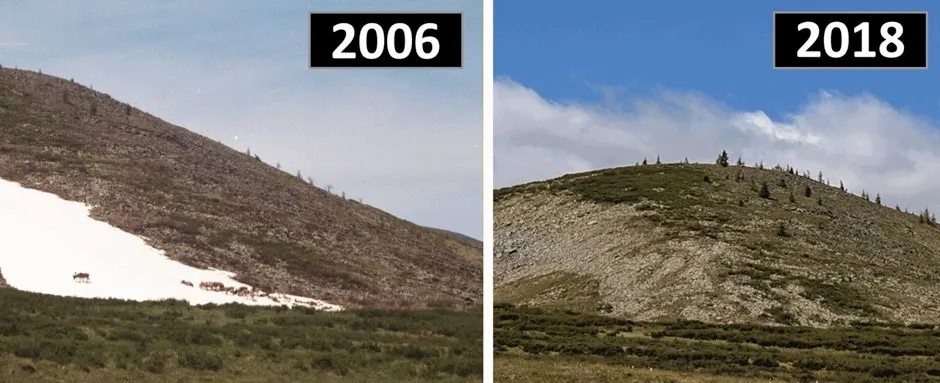

Researchers believe that ice patches, meant to remain intact even in the summer, are thawing in the Khovsgol province in north-western Mongolia and posing a threat to the livelihood of the locals.

They say the so-called “eternal ice” is central to the lives of the Tsaatan people, the region’s traditional reindeer herders, who depend on the snowy patches for clean drinking water and to cool down in summer months.

Read the latest climate change news:

- Climate change 'already damaging the health of the world’s children'

- Climate change declared 'emergency' by 11,000 scientists

- Climate change: extreme weather events could occur every year by 2050

William Taylor, assistant professor in the department of anthropology at the University of Colorado Boulder in the US and study leader, said: “The Tsaatan are literally at the front lines of climate change.

“These are folks that contributed nothing to the problem that we find ourselves in globally, but they’re the ones paying the first price.”

Mongolia is witnessing climate warming at rates exceeding the global average, the researchers say, with summer temperatures already 1.5°C warmer than 20th-Century levels as of 2001.

In 2018, an international team of researchers conducted archaeological surveys in the Ulaan Taiga region in Khovsgol province and spoke to eight of the 30 or so local families.

In their interviews, the herders described how many ice patches had melted for the first time in memory between 2016 and 2018, with many complaining that recent declines in pasture quality had led to reindeer sickness and death, researchers said.

Study co-author Jocelyn Whitworth, a veterinary researcher and owner of the Clearview Animal Hospital in Colorado Springs, US, said: “Access to ice patches has been critical for the health and welfare of these animals in so many ways.

“Losing the ice compromises reindeer health and hygiene and leaves them more exposed to disease, and impacts the well-being of the people who depend on the reindeer.”

In addition, the researchers are also worried that melting ice could affect the region’s archaeological record.

These records are usually obtained from organic materials that have been preserved inside ice and snow for decades, if not centuries, allowing archaeologists a glimpse into the past.

The team recently reported finding a number of wooden artefacts, including an object identified by local people as a willow fishing pole.

But thawing ice has raised concerns that these objects are at risk of degrading rapidly as a result of being exposed to the elements.

Dr Julia Clark, an archaeologist at Flinders University in Australia and the project’s co-director, said: “Archaeology is non-renewable.

“Once the ice has melted and these artefacts are gone, we can never get them back.”

The study is published in the open-access journal Plos One.