A child has become the first patient to receive a transfusion of plasma from people who have recovered from coronavirus through a dedicated treatment trial.

Scientists say the randomised evaluation of COVID-19 therapy, called the RECOVERY trial, tests existing treatments that may help people hospitalised with suspected or confirmed cases of the virus.

The randomly-selected patient is the first of any age to be transfused with COVID-19 convalescent plasma through the recovery trial, according to NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT).

The transfusion took place at the Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital and the patient, who is under the age of 18, is also the first child to receive plasma through the NHSBT plasma programme.

Read the latest coronavirus news:

- Coronavirus: Ibuprofen trial for hospitalised patients begins

- COVID-19 asymptomatic in over 80 per cent of cases, cruise ship study finds

- Coronavirus: reducing distance to one metre increases transmission risk

Although patients have already received plasma through the REMAP-CAP trial, this was not focused solely on coronavirus and only adults in intensive care were able to receive the treatment, according to NHSBT.

Convalescent plasma is the part of blood that contains red and white blood cells around the body. During infection, plasma also contains the antibodies used to fight off the virus.

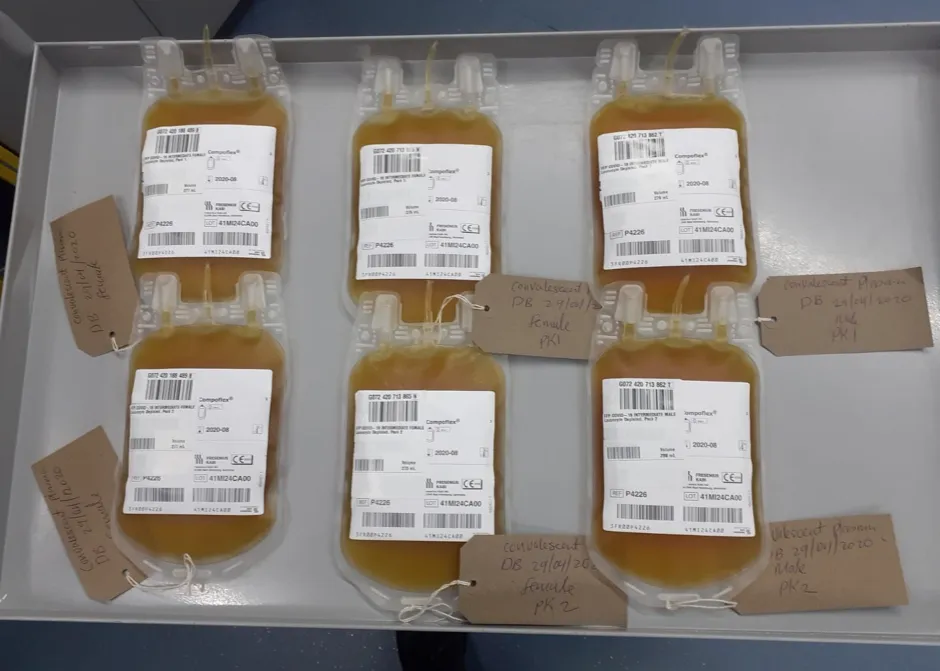

The plasma used in the programme is taken from former COVID-19 patients, meaning it is rich in the specific antibodies that developed during recovery.

If the trial is successful, being treated with convalescent plasma could become a widespread practice in hospitals for those who are seriously ill and struggling to develop their own antibodies.

Selected hospitals are currently able to randomise patients to receive plasma in the recovery trial, which is open to patients of all ages admitted to hospital and being coordinated by the University of Oxford.

Plasma donations are being collected by NHSBT at all 23 of its donor centres in England and, as of 1 June, some 263 units have been issued to hospitals, while a further 267 units are ready for issue.

Prof Richard Haynes, clinical trial lead for the RECOVERY trial said: “Plasma from patients who have recovered from COVID-19 may help to speed up clearance of the virus from those who are currently suffering from the disease and improve their chances of recovery – but we can’t be certain unless we compare it to no additional treatment beyond the usual standard of care received by all patients."

Dr Lise Estcourt, head of NHSBT’s Clinical Trials Unit, said: “This is a welcome milestone and we expect the number of people receiving convalescent plasma transfusions within the trials will now grow.

“We can only provide convalescent plasma thanks to the generosity of people who donate after recovering from the illness. Please help the NHS find out whether this is an effective treatment for COVID-19 by donating plasma," said Estcourt.

NHSBT is appealing for people who have recovered from COVID-19 or the symptoms, and who live near one of its 23 donor centres, to offer to donate their plasma by calling 0300 123 23 23 or visiting www.nhsbt.nhs.uk

How do scientists develop vaccines for new viruses?

Vaccines work by fooling our bodies into thinking that we’ve been infected by a virus. Our body mounts an immune response, and builds a memory of that virus which will enable us to fight it in the future.

Viruses and the immune system interact in complex ways, so there are many different approaches to developing an effective vaccine. The two most common types are inactivated vaccines (which use harmless viruses that have been ‘killed’, but which still activate the immune system), and attenuated vaccines (which use live viruses that have been modified so that they trigger an immune response without causing us harm).

A more recent development is recombinant vaccines, which involve genetically engineering a less harmful virus so that it includes a small part of the target virus. Our body launches an immune response to the carrier virus, but also to the target virus.

Over the past few years, this approach has been used to develop a vaccine (called rVSV-ZEBOV) against theEbola virus. It consists of a vesicular stomatitis animal virus (which causes flu-like symptoms in humans), engineered to have an outer protein of the Zaire strain of Ebola.

Vaccines go through a huge amount of testing to check that they are safe and effective, whether there are any side effects, and what dosage levels are suitable. It usually takes years before a vaccine is commercially available.

Sometimes this is too long, and the new Ebola vaccine is being administered under ‘compassionate use’ terms: it has yet to complete all its formal testing and paperwork, but has been shown to be safe and effective. Something similar may be possible if one of the many groups around the world working on a vaccine for the new strain ofcoronavirus(SARS-CoV-2) is successful.

Read more: