It’s been known for some years that the cat parasite Toxoplasma gondiicauses infected rodents to lose their fear of their feline predators, making them easier to catch, and so making the parasite more likely to spread to other rodent hosts via the cat’s faeces.

However, according to new research by a team at the University of Geneva, the effect of T. gondii is wider in reach and actually leads to infected mice showing a decrease in general anxiety and a reduced aversion to a broad range of threats.

They found that mice infected with the parasite for five weeks or more were more likely to explore novel environments, interact with the hands of the researchers, and investigate the odours of bobcats, foxes, and guinea pigs than their more skittish, uninfected counterparts.

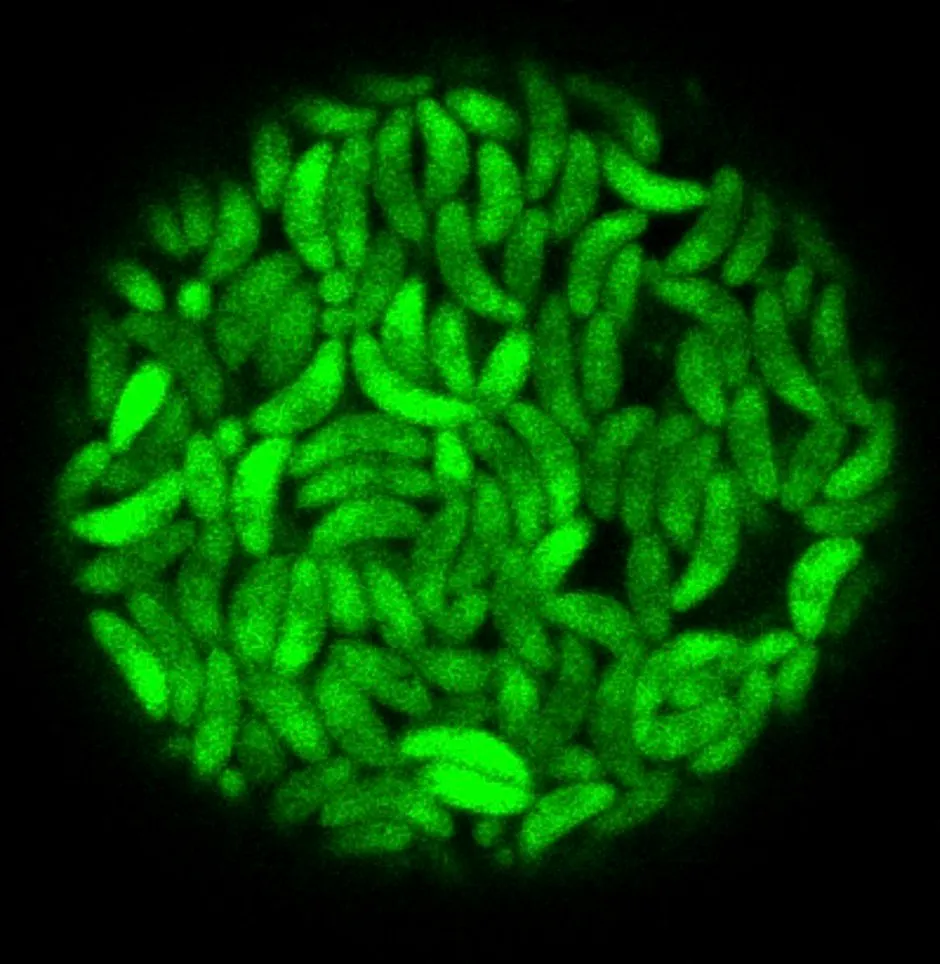

To investigate what was going on the team used a cutting-edge imaging system to accurately map the distribution, size, and number of cysts caused by T. gondii in the brains of the infected mice. They found particularly high concentrations in regions involved in processing visual information and high levels of inflamed neural tissue throughout the brain.

Read more about cats:

- The enduring puzzle of why cats always land on their feet

- Cats do form strong social bonds with their owners

“For 20 years,T. gondii has served as a textbook example for a parasitic adaptive manipulation, mainly because of the specificity of this manipulation,” said co-senior study author Ivan Rodriguez of the University of Geneva.

“We now show that the behavioural alteration does not only affect fear of feline predators but that major changes occur in the brain of infected mice, affecting various behaviours and neural function in general.”

The researchers now plan to further examine how neuroinflammation can alter a range of behavioural traits such as anxiety, sociability, or curiosity.

Reader Q&A: Does my cat only like me for the food?

Would it be so bad if this were the case? Acquiring nutrition is, after all, the daily struggle that all life on Earth faces. In fact, food is what first brought humans and cats together. Chemical analysis of the bones of 5,300-year-old cats from China has shown that these ancient felines were rodent-hunters that lived within grain stores. In essence, we gave them shelter and they took care of the pests.

As time passed, in Western cultures at least, house cats became selected for cuddles as well as their claws. And, from this point onwards, something deeper than cupboard love appears to have emerged.

Just as with dogs, domestication of cats has unlocked a suite of kittenish behaviours. These include grooming, play-fighting and bringing home half-dead mice for a spot of impromptu playtime. These behaviours are about more than food – they’re about family.

In September 2019, scientists announced that cats appear to display traits of the “secure attachment” seen in dogs, where the presence of a human caregiver prompts behaviours signalling security and calmness.

There’s even separate evidence that cats, upon receiving a stroke, get a sudden dose of brain hormones like we humans receive when around our loved ones. So perhaps now, canines have a rival in pursuit of the title of being humankind’s best friend.

Read more: