Some patients that become unresponsive following a significant brain injury retain a degree of ‘hidden consciousness’ and are more likely to make a recovery, neurologists at Columbia University have found.

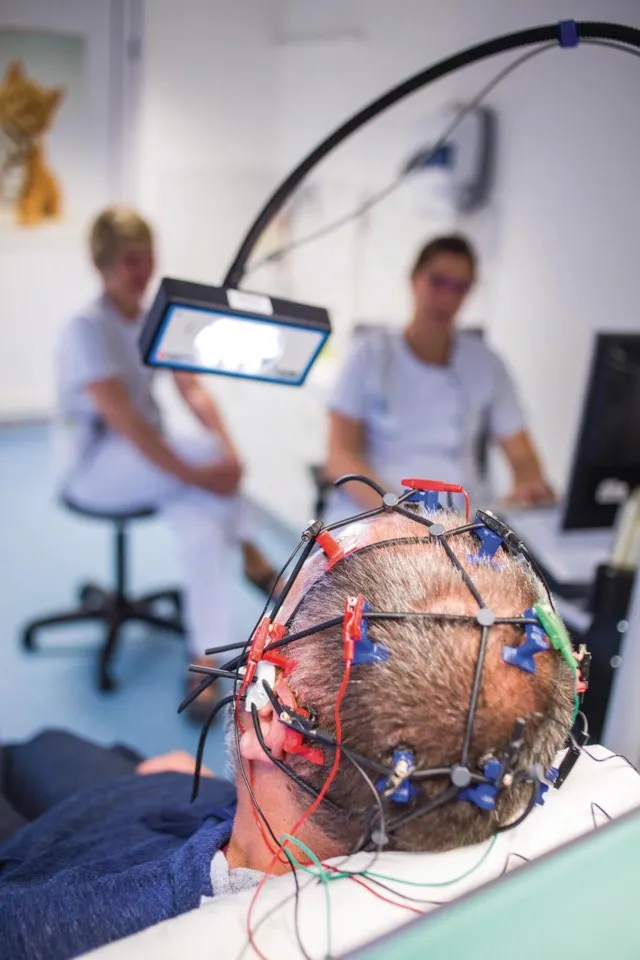

The team used specially designed computer software to analyse standard electroencephalography (EEG) data collected from 104 unresponsive patients to search for specific patterns of brain activity after asking them multiple times to open and close their hands. The idea being that even though they are unable to respond to verbal commands by speaking or moving, the patients are still in some way conscious and can understand the commands.

Read more:

They found that nearly one in seven brain-injured patients in intensive care units (ICU) shows evidence of hidden consciousness just days after injury. “This study shows that some patients who are unresponsive for days or longer may have cognitive processing capabilities sufficient to distinguish commands, and those patients have a higher chance of recovering,” said associate professor of neurology Dr Jan Claassen, who led the research.

“One of the most challenging problems in the ICU involves predicting recovery, and not just survival, for patients who are unconscious after a brain injury. Since the first studies describing hidden consciousness, we’ve been looking for a practical way to do this in the early days after brain injury, when treatment decisions that affect outcomes are often made.”

Within four days of the injury, 15 per cent of the still-unresponsive patients had brain activity patterns on at least one EEG recording, suggesting hidden consciousness. Among these, 50 per cent improved and were able to follow verbal commands before being discharged from the hospital, versus just 26 per cent of those without suchbrain activity.

A year later, 44 per cent of patients that showed the hidden consciousness brain activity patterns were able to function independently for up to eight hours each day, compared with only 14 per cent of those without. However, approximately one-third of patients in each group – those with early EEG evidence of hidden consciousness and those without – died.

The decision to withdraw life-sustaining therapies from patients who appear to have little chance of recovery are frequently made within the first weeks following brain injury, the researchers say. This can lead to difficult discussion between families and healthcare providers.

“Though our study was small, it suggests that EEG – a tool that’s readily available at the patient’s bedside in the ICU in almost any hospital across the globe – has the potential to completely change how we manage patients with acute brain injury,” said Claassen.

Bigger, more thorough, studies are now needed to investigate the technique further, the researchers say.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard