Why is it that you can remember the names of childhood friends that you haven't seen in years yet easily forget the name of someone you just met a moment ago Researchers at Caltech may have found the answer: strong, persistent memories are encoded by ‘teams’ of neurons all firing together to ensure that certain memories stay remembered.

The team developed a test to examine mice's neural activity as they learnt about and remembered a new place. First, they placed mice one at a time in a long, white enclosure with a plus sign marked at one end, a slash sign in the centre, and treat dispensers containing sugar water at either end. As the mice explored, they measured the activity of specific neurons in the mouse hippocampus, the region of the brain where new memories are formed, that are known to encode memories of places.

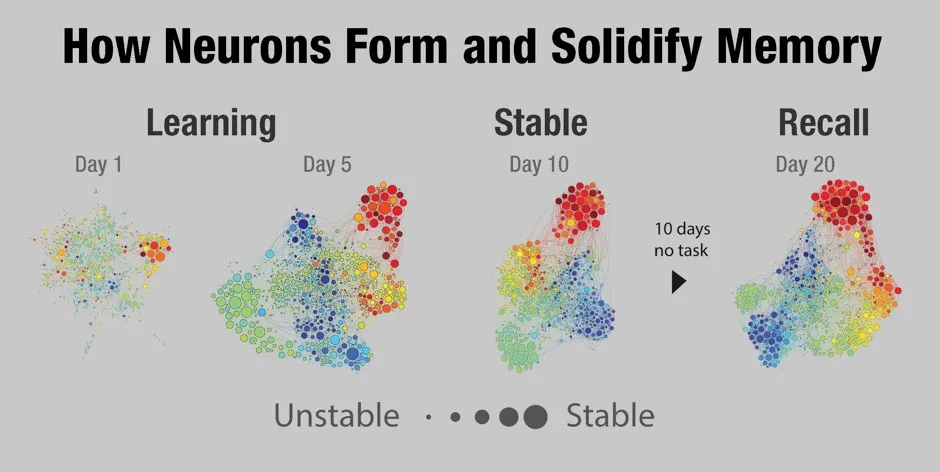

At first, they found that single neurons were activated when the mice spotted one of the symbols. As the mice became familiar with the track, and remembered the locations of the sugar, more and more neurons were activated whenever they spotted a symbol. Essentially, the mice were recognising where they were within the track.

They then returned the mice to the track after a 20-day break. Those that had formed memories encoded by higher numbers of neurons remembered the task more quickly. This indicates that using groups of neurons enables the brain to have redundancy and still be able to recall memories even if some of the original neurons are damaged, the researchers say.

“For years, people have known that the more you practice an action, the better chance that you will remember it later,” said Prof Carlos Lois. “We now think that this is likely, because the more you practice an action, the higher the number of neurons that are encoding the action. The conventional theories about memory storage postulate that making a memory more stable requires the strengthening of the connections to an individual neuron. Our results suggest that increasing the number of neurons that encode the same memory enables the memory to persist for longer.”

Read more about memory:

- Chimps 'working memory' similar to seven-year-old children's

- Controlling brainwaves could help improve memory in Alzheimer’s patients

- Bone marrow transplants could prevent memory loss

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard