- People with blood type A may be more vulnerable to COVID-19, study claims.

- Researchers found that of the 206 patients in the study who died, 85 had blood type A, equivalent to 41 per cent of all deaths.

- Advice is still to wash your hands and follow the guidelines issued by authorities, whatever your blood type.

People with blood type A may be more susceptible to coronavirus compared to other blood types, scientists have claimed.

Researchers in China looked at blood group patterns of more than 2,000 people who had been diagnosed with the new coronavirus as part of a preliminary study.

They found that those with blood type A were more vulnerable to infection and tended to develop more severe symptoms while those with the more common blood type O had a “significantly lower risk” of getting the disease.

Although the study is yet to be peer-reviewed by other academics, the team are urging medics and governments to consider blood type differences when treating patients with the virus and helping prevent the spread of the disease.

The paper is currently a 'pre-print', meaning it hasn’t been vetted by a group of scientists who will assess if the science – the method, the analysis and the inferences drawn from the data – stands up, and it hasn't been published in a journal. The peer review process is designed to weed out errors, misinterpretation or flawed research methods. But in order to speed up the distribution of research (as the peer review process takes time) scientists do post papers to pre-print archives first.

Latest coronavirus news:

- Coronavirus vaccine: first volunteers receive trial dose in US

- Is hand-washing really the best thing we can do to stop the spread of COVID-19?

- Aggressive 'L type' strain affecting 70 per cent of coronavirus cases

- Coronavirus vaccine: UK scientists work to avoid future outbreaks

The researchers, led by Wang Xinghuan of the Zhongnan Hospital at Wuhan University, looked at the blood of 2,173 people who had been diagnosed with the coronavirus from three hospitals in the Hubei province.

They found that while blood type O (34 per cent) is more common in the general population in China than type A (32 per cent), around 41 per cent of COVID-19 patients had blood type A, whereas people with type O accounted for just 25 per cent.

Of the 206 patients in the study who died, 85 had blood type A, equivalent to 41 per cent of all deaths, the researchers said.

Speaking to South China Morning Post, Gao Yingdai, a researcher with the State Key Laboratory of Experimental Haematology in Tianjin, said while the research may be helpful to medical professionals, the public should not worry too much about the findings.

She added: “If you are type A, there is no need to panic. It does not mean you will be infected 100 per cent.

“If you are type O, it does not mean you are absolutely safe, either. You still need to wash your hands and follow the guidelines issued by authorities.”

Read more about viruses:

- How do scientists develop vaccines for new viruses?

- How do viruses jump from animals to humans?

- Do viruses die?

In the UK population, 48 per cent have blood type O, making it the most common blood group, while 38 per cent have type A.

GPs do not routinely check people’s blood groups so for those wanting to know their blood type, one of the options is to donate blood through the NHS Blood and Transplant, which will be recorded on the official donor card.

How do viruses make us ill?

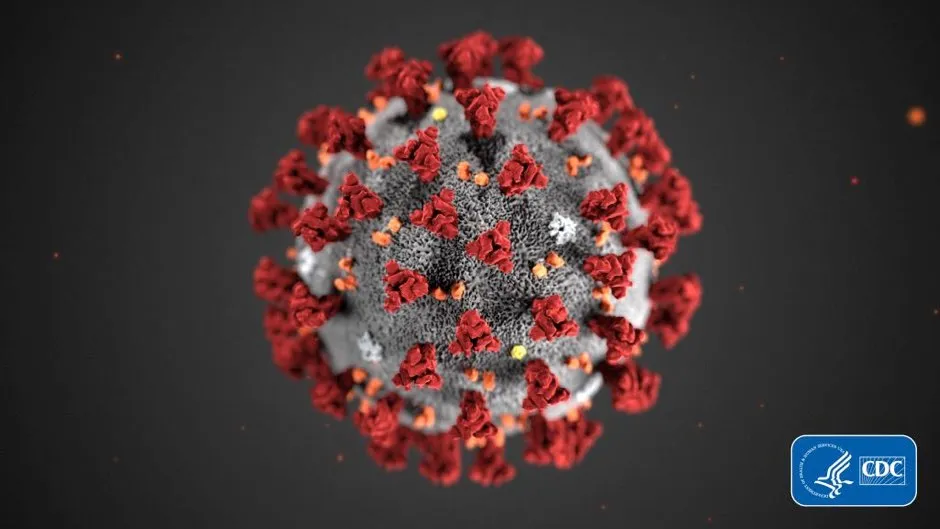

Viruses are extremely tiny parasites made of genetic material, wrapped in proteins and sometimes an outer membrane layer, which hijack living cells to reproduce themselves. We’re exposed to viruses every day, but our immune system prevents the vast majority of them from taking hold – especially those that we’ve fought off before, or been vaccinated against.

The first stages of an infection happen when a virus gets past our physical barriers of skin and mucus, and enters a suitable cell. Once inside, a virus can take over the cell, forcing the cell to make many copies of the virus (replicate), which damages the cell and sometimes kills it. The newly-made viruses are released to find a new cell. We get ill when a virus has established an infection in many cells, and our body’s normal functioning changes.

Viruses often infect specific places in our bodies, which is where we feel their effect. Rhinoviruses infect our upper airways behind our nose, and we respond with snot and sneezes: a common cold. The coronavirus that emerged in 2019 (called SARS-CoV-2) infects our lower airways, including our lungs, leading to pneumonia.

Our body fights viruses by creating an inflammatory response and calling in specialist cells from our tissues and organs. Some of these cells can make antibodies against the virus, some destroy the infected cells, and others build a memory of the virus for next time. Some of the things that make us feel ill – snot, fever and swollen lymph nodes, for example – are due to our body’s battle to get rid of the virus, not because of the virus itself.

Read more: